THE Great Wall of China, the Pyramids at Giza, the Grand Canyon, the Coliseum, the Rose Red City of Petra, Niagara Falls, Pompeii, Machu Picchu, the Parthenon, the Tower of London, the Great Barrier Reef, the Taj Mahal.

They are among the greatest man-made and natural treasures on Earth and have been duly acknowledged so as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Despite its undoubted place in the annals of our Victorian industrial heritage you would have to be barking – or maybe a dyed-in-the-wool Swindon railway fanatic – to place the town’s historic railworks among that lot.

However, the Government’s announcement that the Forth Bridge had been nominated for World Heritage status reminds me of an initiative to have the Swindon Railway Works similarly inscribed.

Or to be more accurate, to see our former locomotive and carriage complex, along with the Railway Village on the other side of the track, located at the heart of a new World Heritage Site (WHS) – to wit, the Great Western Railway line from Paddington to Bristol.

The move, as I recall, provoked wry amusement and cackles of derision in some quarters. Let them scoff. The story had legs, as they say in the newspaper business. It gained considerable momentum and chuffed along for 13 years before finally hitting the proverbial buffers.

It wasn’t, of course, the entire 116 miles of track that prompted a wagon load of academics, engineering experts, heritage chiefs, railway bosses, museum curators and industrial archaeologists to champion the cause.

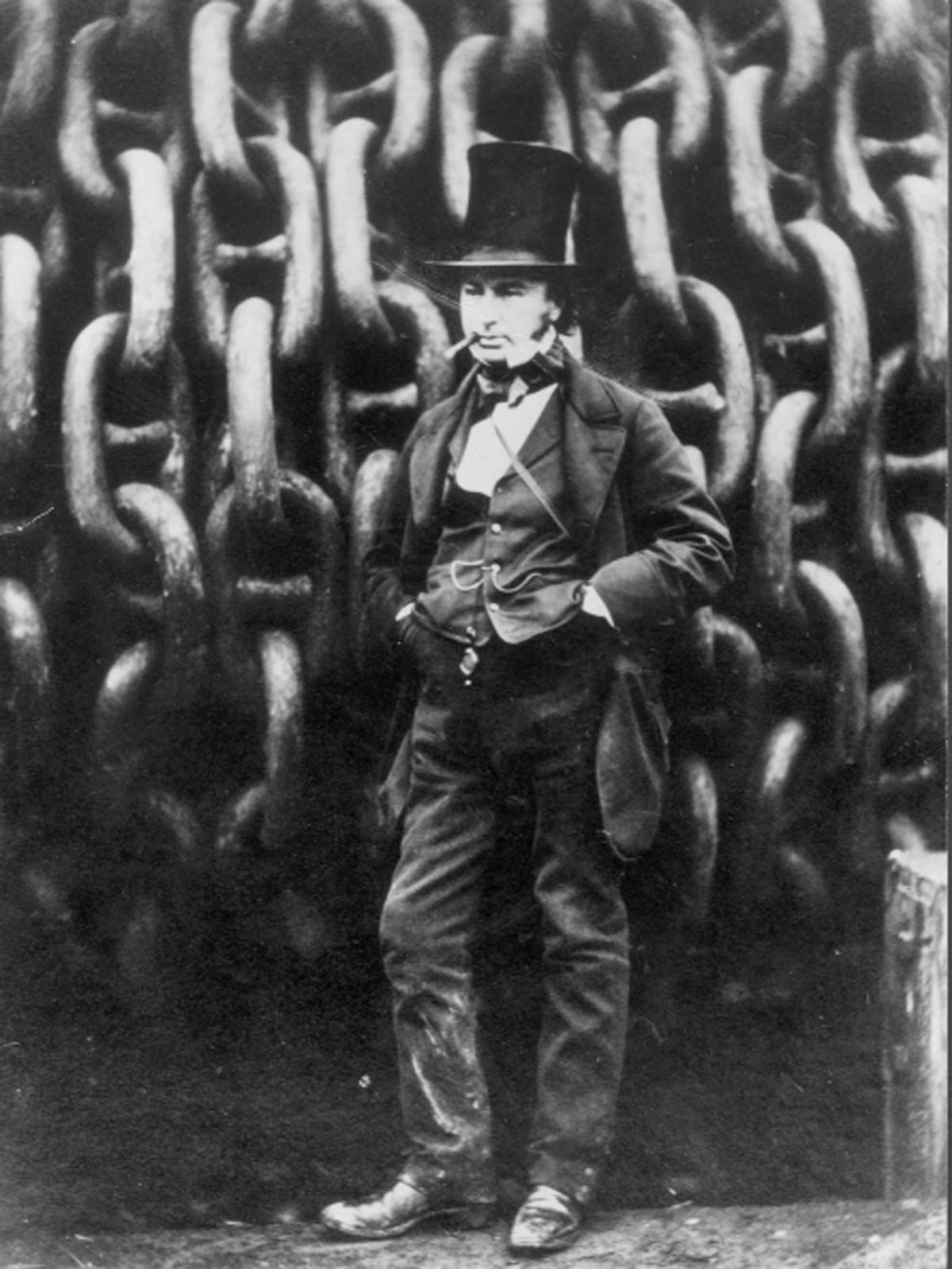

It was the engineering and architectural gems dotted along the route that would, so the plan went, collectively comprise the WHS. Think of a string of pearls. The string, unimportant. But the pearls… These would be a series of landmark 19th century structures built or overseen by Isambard Kingdom Brunel as he forged his railway line west during the 1830s, overcoming a succession of hurdles with one technical or engineering innovation after another.

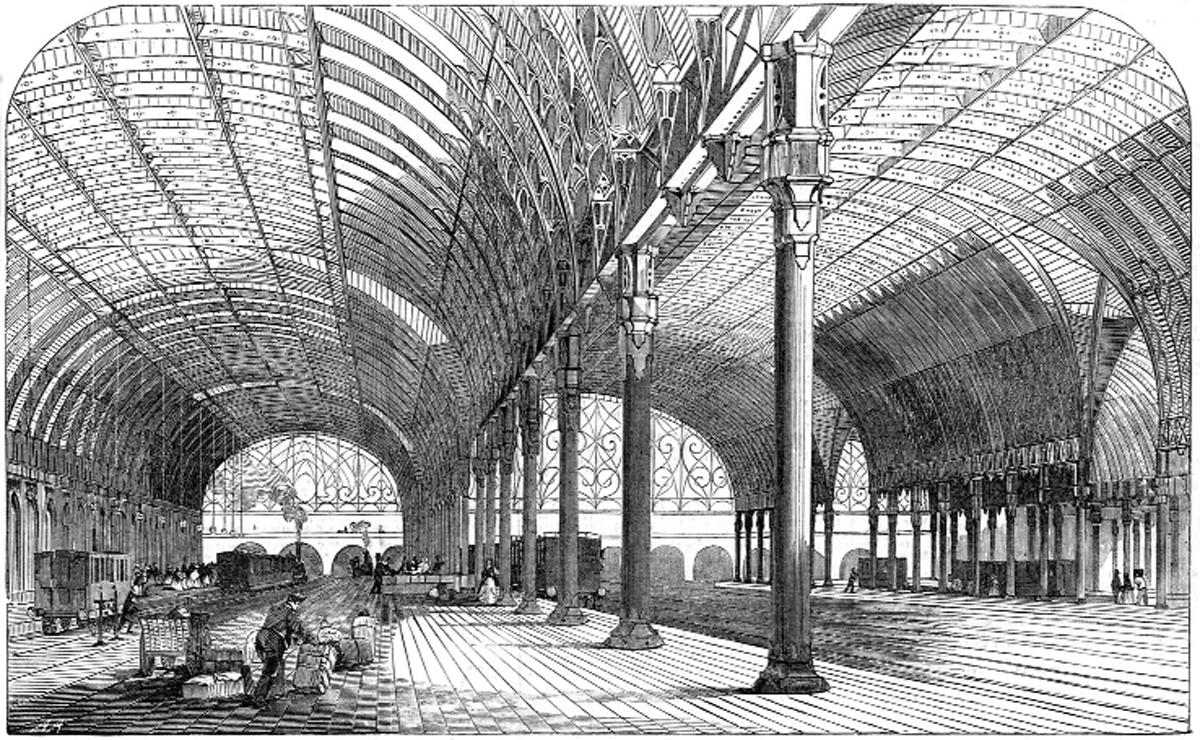

Paddington station, Maidenhead Bridge, viaducts at Hanwell and Chippenham, the Swindon Works and Railway Village, Box and Middle Hill Tunnels, problematic sections from Sydney Gardens to Twerton Tunnel, and the River Avon to Temple Meads in Bristol.

Together they comprise, as the chairman of English Heritage Sir Neil Cossons succinctly put it at the time: “The legacy of Brunel’s robust genius.” An additional suggestion was that the proposed WHS should extend a mile from Temple Meads to the dry dock where Brunel’s SS Great Britain – “the ship that changed the world” – resides.

The initiative began in earnest in 1998, not with a posse of die-hard railway buffs eulogising our engineering heritage over pints of Guinness in a smoke-filled Swindon tavern, but with a declaration by the then Culture Minister Chris Smith that the London/Bristol line was “a masterpiece of human creative genius.”

Placing it among a list of 32 potential UK World Heritage Sites, the minister sparked a string of events which culminated on Friday, October 17, 2003 with a day-long symposium at the University of Bath in Swindon’s Oakfield campus.

Organised by the university in conjunction with English Heritage, I attended the event and still have the programme, grandly entitled “The Finest Work in the Kingdom? – The GWR as a World Heritage Site” sporting on the front an atmospheric image of Box Tunnel’s ornate western portal.

An impressive selection of speakers took the rostrum including the aforementioned Sir Neil along with experts who focused on various aspects of the GWR line: “Brunel’s innovatory approach,” “the architecture of the termini,” “Brunel’s distinctive building styles for bridges and stations,” “GWR – The Legacy,” “The line, stations, Swindon Railway Works and Village.”

No-one was actually saying that the engineering diamonds strung along the London-Bristol railway track were, even as a collective entity, up there with Notre Dame Cathedral, the Acropolis, the Blue Mosque, Ayers Rock, Christ the Redeemer or Victoria Falls.

However, there are currently 890 World Heritage Sites, not that many of which are as iconic or instantly recognisable as Sydney Opera House or the Walls of Jerusalem: important though they are, many are not even well known outside of their immediate region.

And when you look at some of the UK’s 28 World Heritage Sites – at least, those with an industrial bent – then there is certainly a case for the GWR line to take its place among them.

They include Bleanavon’s 19th century iron and coal mining landscape in South Wales (inscribed 2000), the Derwent Valley Cotton Mills near Derby (2001), Cornwall and West Devon’s Mining Landscape (2006), the Ironbridge Gorge (1986), Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City (2004), Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and Canal in North Wales (2009) and the 19th century Saltaire industrial village near Bradford (2001.) The above are all, by and large, relics of a bygone age that are now primarily tourist/visitor attractions. This is also true of the Swindon railworks and the SS Great Britain.

However, virtually all the other sturdy, pioneering and often aesthetically pleasing structures scattered along the GWR line remain – after 170 years – in full use today… and take a daily pounding from high-speed trains that the early Victorians could hardly have dreamt of.

As it happened WHS submissions by Liverpool, the Welsh aqueduct/canal and the Cornish/Devon mining landscapes succeeded while the GWR – along with a string of other bids – fell by the wayside.

Four years ago the London-Bristol line was among a new list of potential WHSs, prompting former Swindon Mayor Steve Wakefield to pronounce: “It’s absolutely great news.

“The Great Western Railway is without any doubt one of the world’s greatest achievements from the early part of the 19th century.”

But this, too, was derailed and for the time being we will have to make do with that World Heritage Site a few miles down the A4361, Neolithic Avebury (twinned with Stonehenge.) Until, that is, the GWR steams in with another bid for world fame.

- Brunel’s technical ingenuity was tested by a constantly varying and problematic terrain during the six years that it took to build the line (1835-1841.)

Between the Bath and Bristol section alone there are three viaducts, four major bridges and seven tunnels.

On Brunel’s achievement, historian Sir Kenneth Clark wrote: “Every bridge and every tunnel was a drama, demanding incredible feats of imagination, energy and persuasion, and producing works of great splendour.”

His greatest obstacle, blasting a tunnel of nearly two miles through Box Hill between Chippenham and Bath, was considered impossible by many.

It took five explosive years and was achieved at a terrible price as more than 100 workmen died.

Folklore has it that Brunel deliberately aligned the tunnel so that the rising sun could be seen throughout its length on just one day of the year: April 9 – his birthday.

Opinions vary widely on this intriguing claim but engineer Angus Buchanan, writing in 2002, said that new calculations “convinced me that the alignment on April 9 would permit the sun to be visible through the tunnel soon after dawn on a fine day.”

- I read with great interest your article And The Mummy Returns (Swindon Advertiser, January 15). You see, I spent many school holidays visiting the museum in Bath Road and remember seeing the Mummy but on future visits it had disappeared. (This is when I think it was moved).

Charles Gore was my paternal grandfather (please see attached photo). I was born in his house, 2 Carlisle Avenue, Swindon, on Christmas Day 1946. Your article told me about times in his life which I did not know about and have found fascinating. I can’t believe that I am reading about him now as he has great, great grandchildren in Swindon. I look forward to the opening of the new museum.

What I do know was that he was given the Freedom of the Borough of Swindon in 1933, (my brother has retained the scroll) and was presented to King George VI and Queen Mary when they visited Swindon and that his draper’s shop in Granville Street was run by my grandmother and father until about 1963.

I was five years old when he died so I did not get to know him too well but did see his drawings and knew that he collected fossils. Thanks once again.

Susan (Gore) Sawyer, Shaftesbury Avenue, Swindon

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here