ON a crisp autumnal day just over 20 years ago a group of smartly turned-out pensioners – blazers, suits, ties, shoes so shiny that you could virtually make out your reflection in them, etcetera – converged from all corners of the country onto a village near Swindon.

Tentatively eyeing each other up while squinting at the bright yellow name-tags they all wore on their lapels they were endeavouring to make out a familiar face or two, or perhaps detect the echo of a voice last heard more than half a lifetime ago.

Grins emerged, backs were slapped and hands firmly shaken. Down at The Radnor Arms toasts were raised in memory of lost comrades as the hubbub of excited chit-chat and clinking glasses grew steadily louder.

Mostly in their 70s and 80s their numbers included retired miners, civil servants, bank workers and a preponderance of rural workers such as farm labourers and game-keepers.

A disparate bunch in all but with one thing in common – a bond that would tie them together for the rest of their lives.

When they were mostly in their teens and 20s during the Britain’s darkest days they were recruited for a Secret Army… an organisation so closely guarded that no-one outside of their immediate circle knew of its existence until 20 years later.

Some even suffered the ignominy of being branded cowards for brazenly walking the streets of war-time Britain while most of our boys were fighting overseas.

And so to the cream-stone village of Coleshill on Tuesday, October 25, 1994 when surviving members of this hush-hush unit gathered for the first time in half-a-century.

“It was great fun blowing up walls in the middle of the night,” laughed Gordon Jones, 72, as the beers, gin-and-tonics and reminiscences flowed freely.

They would go out on a night patrol, he recalled, and maybe inch towards a spot where troops-in-training were camped. Then they would “ginger them up” – nice expression, Gordon – with a few harmless explosions. “That got ‘em going.”

Amidst hoots of laughter and nods of agreement from his old muckers Gordon, added: “Our parents knew nothing about it. They thought we were in the Home Guard.”

But Dad’s Army they weren’t. With their wooden rifles and make-shift military vehicles the Home Guard were a familiar sight across the nation during World War Two.

The Auxiliaries, as they were somewhat blandly known, were a strictly cloak and dagger outfit. And a deadly one at that. Among the many skills they learnt was how to kill swiftly, ruthlessly and silently.

Wives, girlfriends, brothers, best pals or, as Gordon alluded, parents didn’t have a clue what they were up to. Just the chosen few – some 3,000 in all – were in on the secret, along with a small clique of trusted Churchill bigwigs.

Oh yes, and the silver-haired postmistress who worked down the road in hill-top Highworth. She knew all about their nefarious escapades. Indeed, she was a vital cog of a network that was, in effect, the British Resistance.

I am reminded of this covert band of confederates following an internet appeal this month for fresh information on the Auxiliaries before such knowledge simply vanishes.

So who were the Auxiliaries – and why Coleshill?

With the Nazis just a few miles away across the Channel, an invasion in 1940 seemed inevitable. What was required, then, was a posse of undercover oppos to harass, hobble and nobble the invaders as they made in-roads into Britain.

Those chosen for a task that would almost certainly end in death were either too young or old for the armed forces, or in reserved occupations.

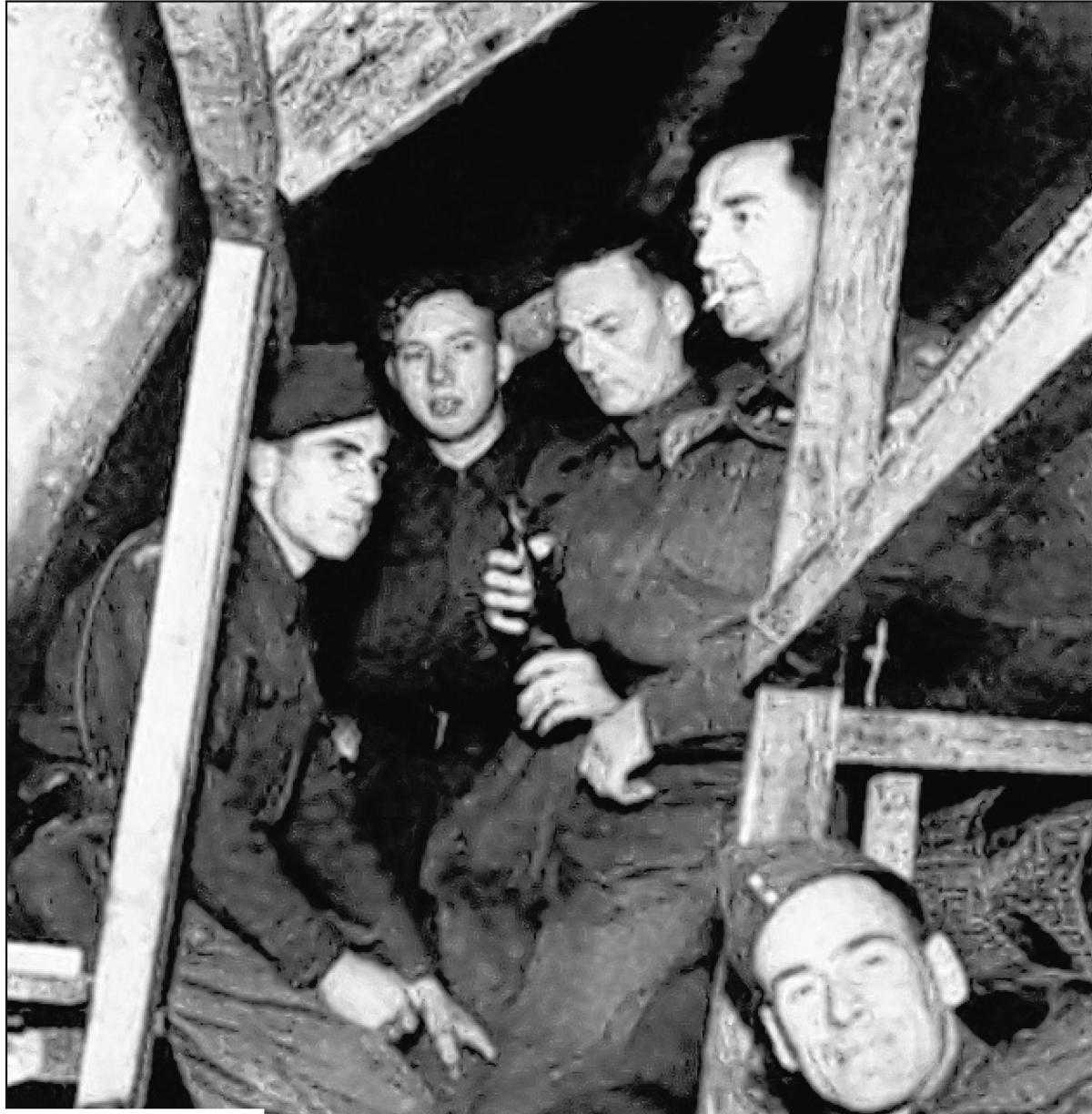

Equipped with the latest weapons – often acquired before the regular Army – their mission, come the invasion, was to head for their self-made bunkers in the countryside.

There they would wait like moles for the invading army to pass before emerging to cause disruption and havoc by destroying transport, blowing up railways, setting up booby-traps and “dealing” with collaborators. Absolutely anything, in fact, that would hamper the Nazi advance in order to aid a British counter-attack.

Eight or so miles from Swindon, 17th Century Coleshill House was chosen as the Auxiliaries’ remote HQ where the resistance boys were instructed in the fine arts using explosives, hollowing out bunkers and “silent killing.”

As we all know our guerrilla army – hundreds of units scattered across the country – never saw action, Hitler having decided to invade Russia rather than Britain.

The unit was disbanded in 1944 but having signed the Official Secrets Act this crack band of stealthy saboteurs couldn’t breathe a word.

Many an auxiliary went to the grave with the secret intact. Indeed, they were told by their commander Colonel Frank Douglas all those years ago that in view of the unit’s secrecy “no public recognition will be possible.”

Sadly, when around 60 former Auxiliaries finally reconvened 20 years ago their old war-time haunt, Coleshill House was no more.

The once stately mansion had been burnt to the ground in 1953 as a result of a bungling builder with a blow-torch. It is sad to reflect that the majority of those at Coleshill that day – some of whom I was lucky enough to interview – are probably no longer with us.

One of the oldest survivors, Jack Archer, 86, of Highworth, recalled at the time: “We were ready for the Germans. I think they knew about us although we never said a word to anyone. Not even my wife knew.”

After his war-time activities were finally revealed Captain Archer received letters of apology from those who once scorned him as a coward, including a woman whose three sons were stationed overseas.

“She put a white feather in my coat and asked me why I wasn’t fighting. Obviously, I couldn’t say…”

Mabel Stranks

TALL, well-spoken and steeped in the Victorian values of her upbringing, post-mistress Mabel Stranks was a respected figure in the rural community where for almost 50 years she dispensed stamps, stationery and sound advice.

She was remembered in Highworth as “a real matriarch and a stickler for everything being done in the right way.”

But no-one, not even her closest family, knew that mother-of-three Mrs Stranks played a pivotal role in the British Resistance during the war.

It was her job from 1941 to 1944 to “vet” potential recruits for the Auxiliaries who had been sent from around the country to Highworth post office.

Satisfied of their credentials she used codes and passwords to contact the unit and ensure they were conveyed to its secret HQ at Coleshill.

It wasn’t until more than 20 years later with the publication of a book that Mrs Stranks’ patriotic war effort came to light.

In the event of a Nazi invasion her name would have been high on Hitler’s hit list of “wanted” British insurgents.

On October 26, 2001 – 30 years after her death at 88 – a plaque was unveiled at the town’s former post office honouring Mrs Stranks’ dutiful role in the war.

Ted Jefferies

WHEN Ted Jefferies was recruited by the Auxiliaries as a messenger boy he was too young to sign the Official Secrets Act – so he was sworn to secrecy on his Scouts’ oath.

Phone calls being too risky, Highworth schoolboy Ted, 13, passed paper notes between the group’s HQ at Coleshill and various units in the location including an Auxiliaries centre at Hannington.

He was also given a Fairbairn Sykes fighting knife – the chosen fighting blade of the Auxiliary Units – “just in case.”

As a scout it was hoped that his movements would go unnoticed by an occupying German Army.

Until his death at 82 last year Ted – who later worked for the GWR in Swindon – was one of a dwindling band of former British Resistance members.

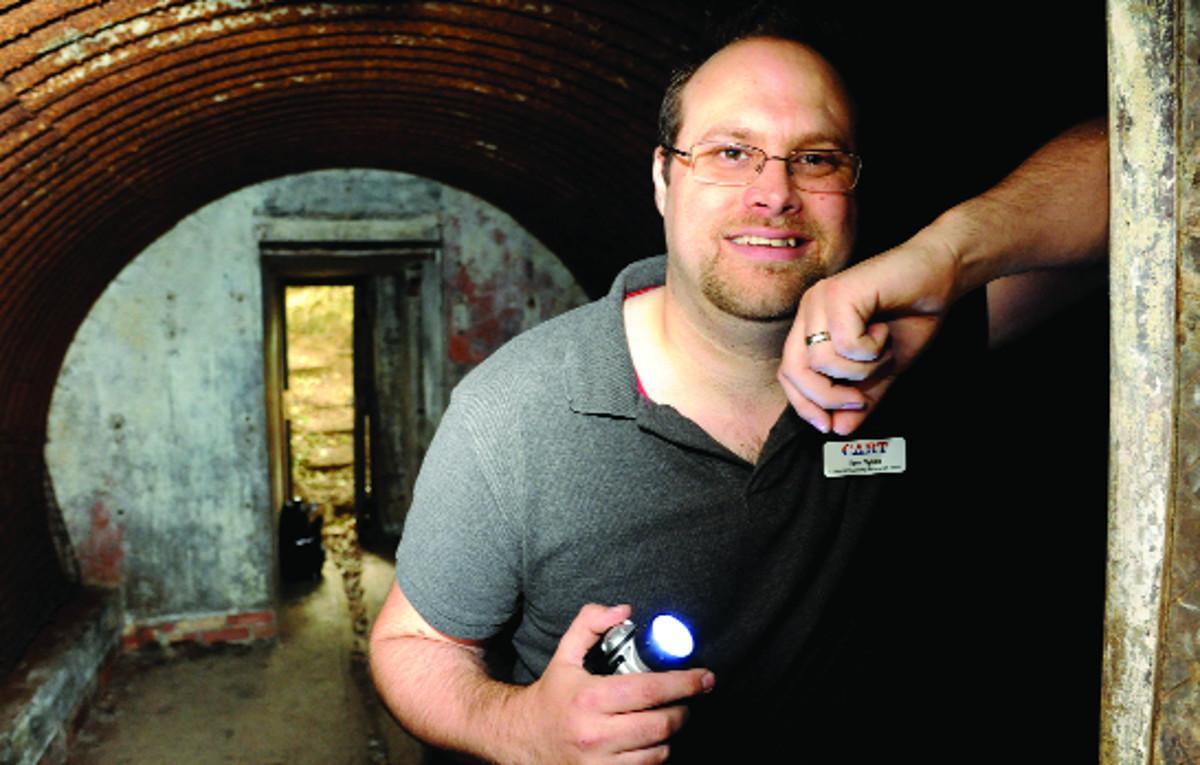

The group’s history is today traced and celebrated by the Coleshill Auxiliary Research Team (CART) which is keen to locate unit bunkers, hundreds of which are believed to hidden throughout the countryside.

Further information on CART is available at www.coleshillhouse.com/about-us.php

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here