IT was a strange kind of passion for a book-mad youngster weaned on the paperback thrillers of Edgar Wallace – crammed, as they were with adventure, murder and mystery – but something almost anybody ever forced to endure endless Sunday school sessions could easily identify with.

Mark Child became interested in church architecture after yawnfully gazing at his ecclesiastical surroundings while being “bored stiff hearing the parable of the Good Samaritan for what seemed like the 27th time,” as he put it to this newspaper more than 30 years ago “The frustrated teacher told me to go and sit at the back of the church,” he recalled. “I began to count the bricks in the wall. I noticed that the church was lop-sided – and this began my interest.”

It culminated, years later, in the publication of a series of his books on the subject before he went on to become not only one of Swindon’s most prodigious and frequently published authors but also one of our finest and most prolific historians.

Mark Child, who has died at the age of 72 after a short illness, made a unique contribution to Swindon’s history and heritage. His “encyclopaedic knowledge of the town,” as one fellow historian described it, was acquired as a result of half a century of painstaking research.

It is easy to imagine Mark Child knee deep in dusty files, yellowing documents and countless back copies of the Swindon Advertiser, studiously probing aspects of our town’s past that would otherwise have vanished but for his fervent work.

Born in Ermin Street, Stratton St Margaret in 1943 Mark was a pupil of Wantage’s King Alfred Grammar School where he received a school prize from Poet Laureate John Betjeman.

Already an avid writer by then, he had scored his first success with an article in Enid Blyton’s Sunny Stories for which he received a princely two-and-six (12 and a half pence – not to be sneered at for a 1950’s schoolboy.) Fired with encouragement and enthusiasm, he sent off all sorts of short stories and articles to all sorts of magazines and publications on all sorts of subjects. “It was more interesting and more remunerative than homework.”

After leaving school the teenage bookworm with a thirst for knowledge landed a post at Swindon Library as its first ever assistant librarian – a satisfactory collision of work and pleasure.

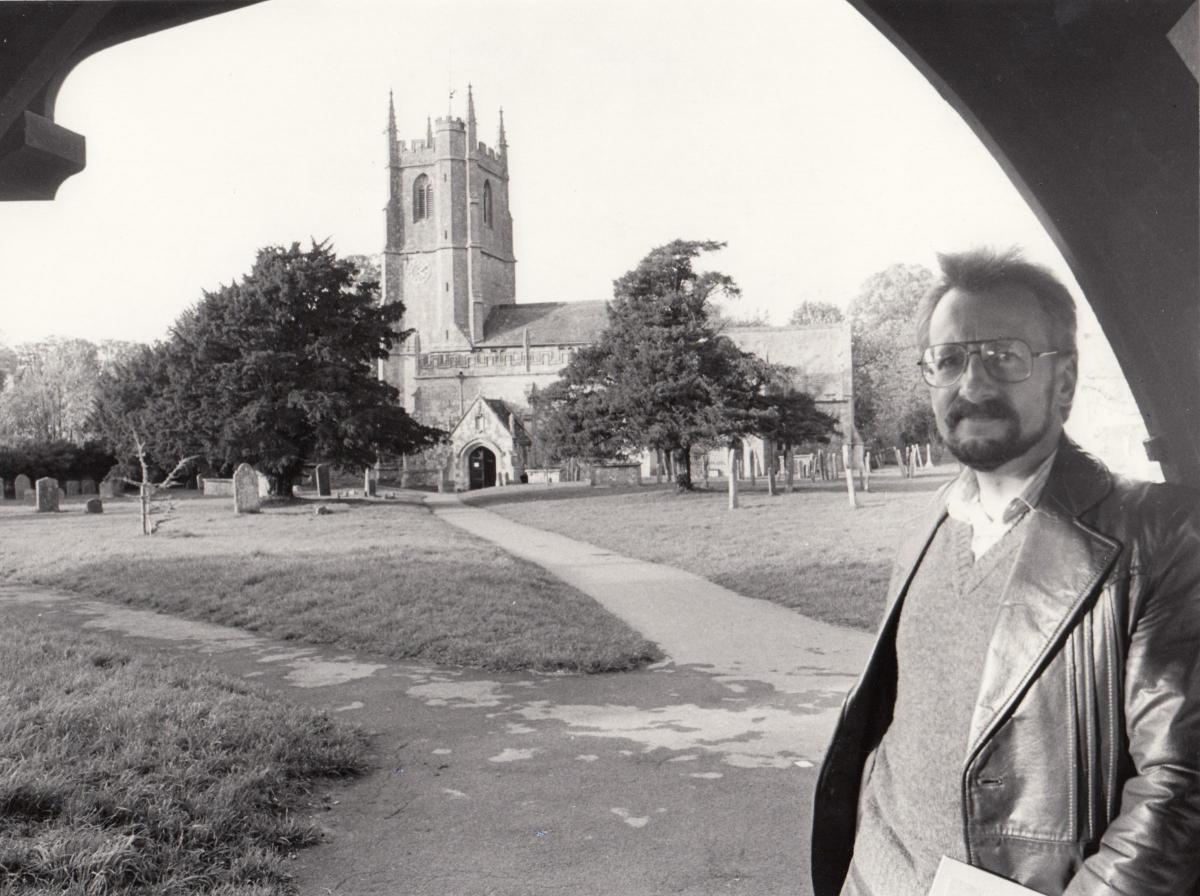

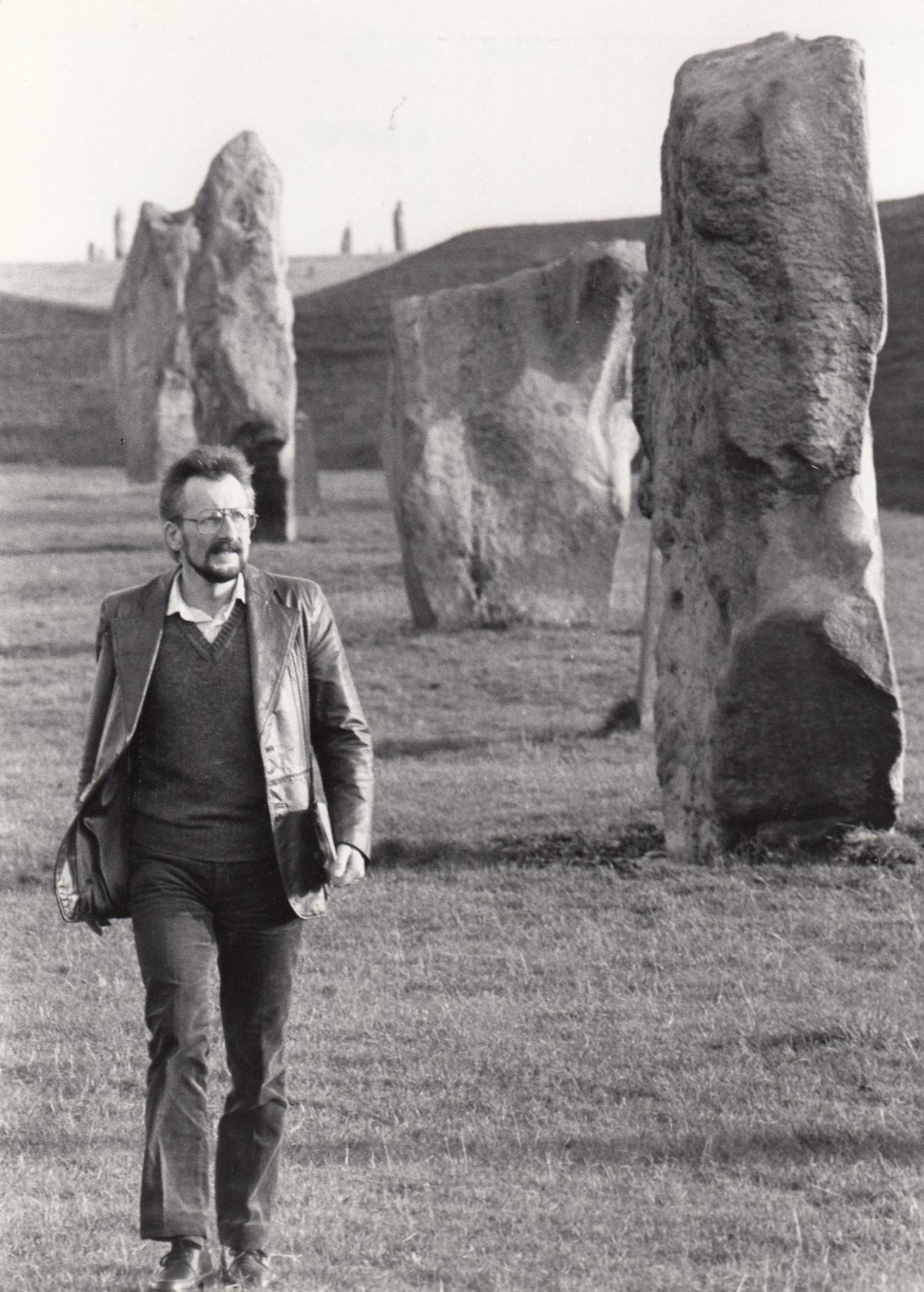

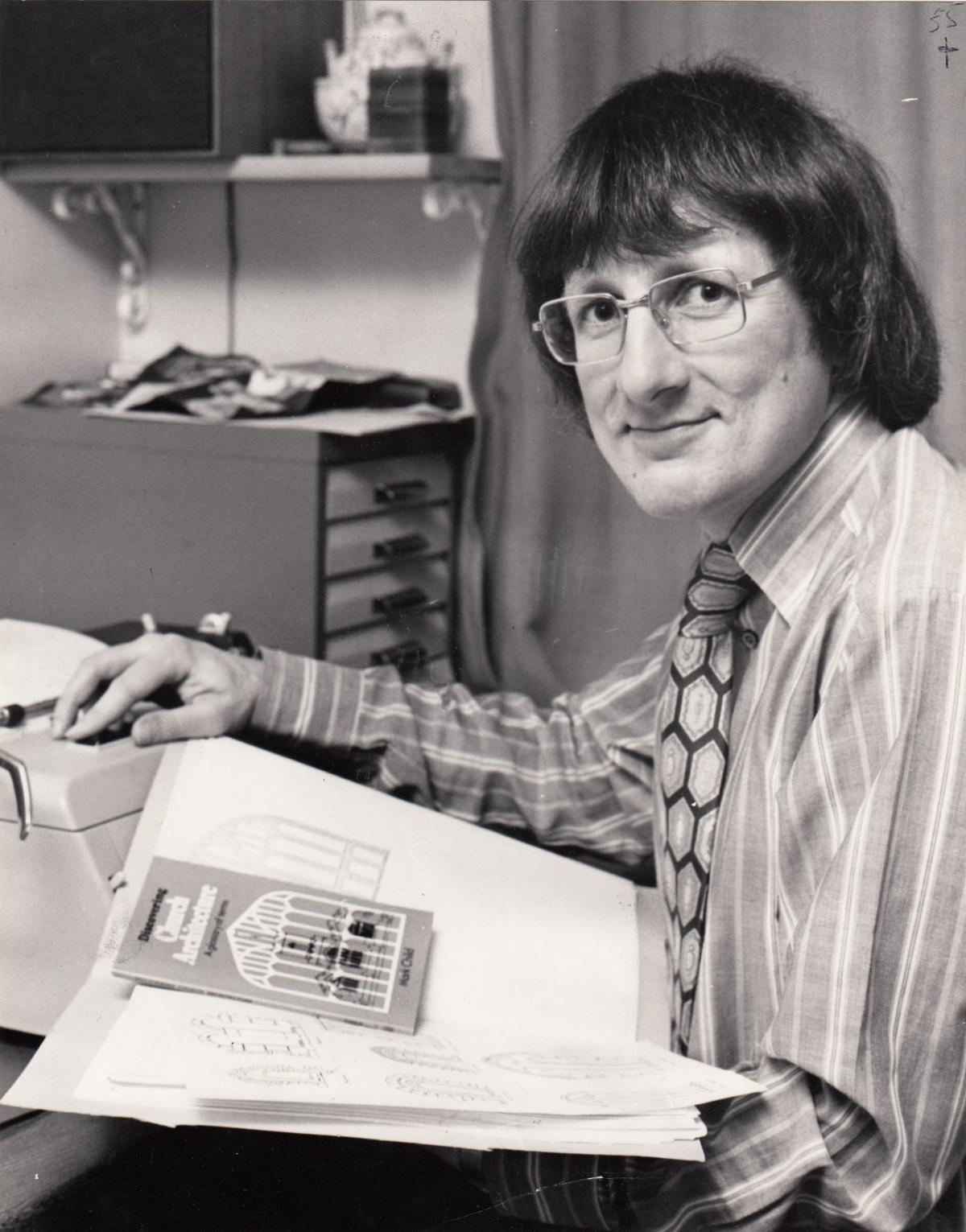

By then he was scouring churches in Wiltshire and beyond gathering data for the book Discovering Church Architecture.

Poking around graveyards paved the way for a follow-up, Discovering Churchyards, before he wrote and illustrated – with some quite beautiful drawings, clever man – Batsford’s English Church Architecture: a Visual Guide.

Mark became an expert on objectively appraising such structures – all self-taught. “In my teens it was almost a second occupation (studying churches,)” he told us in 1984. “I’m as well read as anyone can be as a layman.”

The eerie ambience of churchyards led to an off-shoot publication – Local Hauntings, a checklist of recorded ghosts in Wiltshire. The stuff just poured out of him with publications on poetry, architecture, markets, fairs, mills, legends, myths and folklore... and even The Evacuation of Dunkirk. His output was appearing in everything from children’s comics to the Financial Times.

An early effort saw Mark descend into dank and presumably cobwebbed cellars of long-established Swindon firms in search of “undiscovered documents” which helped him produce the thesis Aspects of Swindon History.

He didn’t exactly make a fortune from his writings – sometimes he barely covered his research costs. Job-wise, he worked for WH Smith and Book Club Associates as an editor, writer and public relations consultant.

Typewriter ribbons continued to be chewed to shreds before the advent of the computer and by 1987 Mark produced the first Shire guide to Wiltshire.

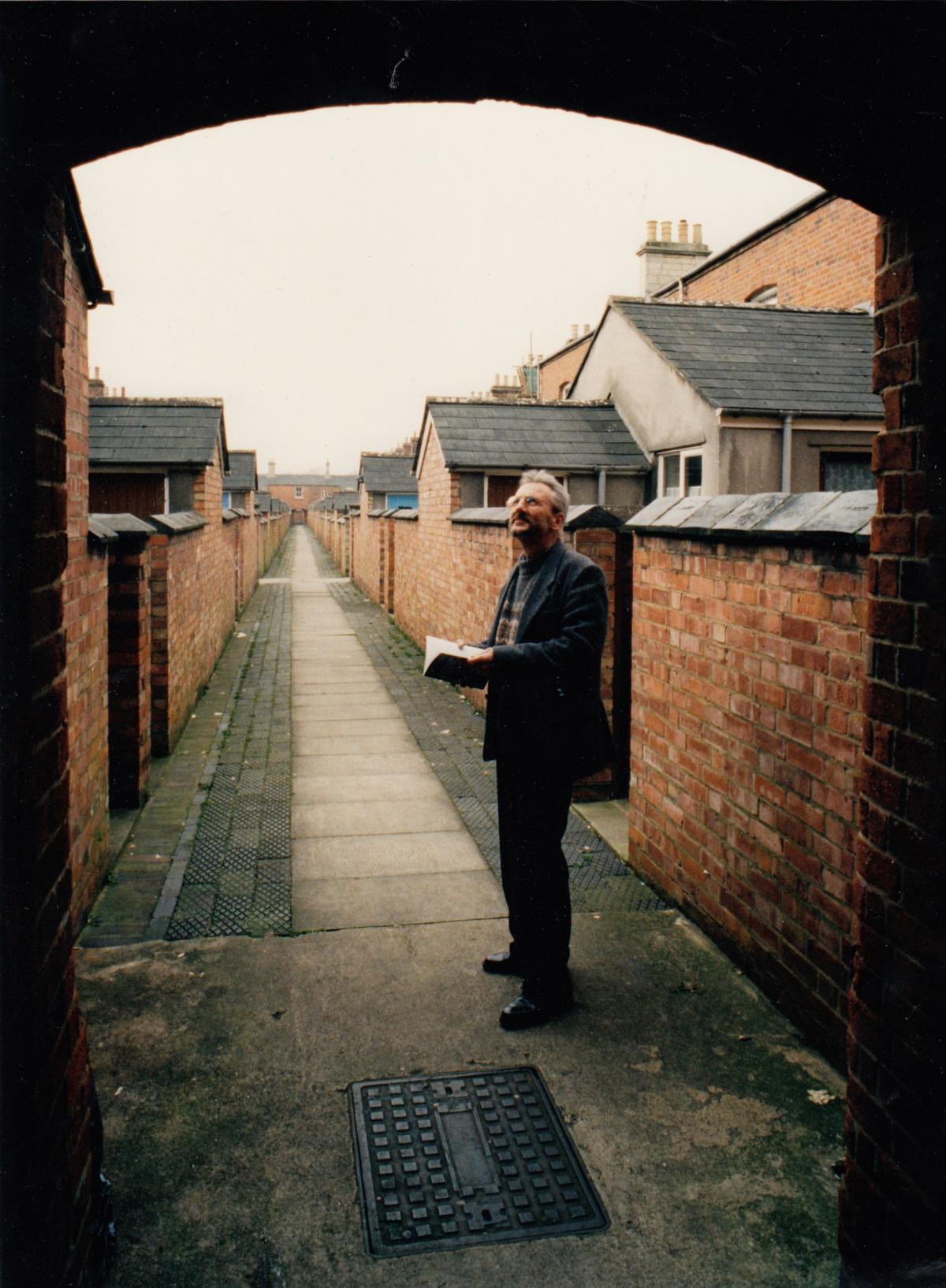

I spoke to Mark in 2002 upon the publication of one of the most important books ever written on the town, Swindon An Illustrated History – the result of 40 years meticulous fact finding.

You could say it was a follow-up to the one written by Swindon’s first historian, Adver founder William Morris. “But that was in 1885 – and half of it had nothing to do with Swindon,” explained Mark. “There are several reasons for this (his new book) – the main one being the generalisation that Swindon has always been a railway town.

“In fact, it was a thriving community for centuries before the railways came and it ceased to be dependent on them decades ago.

“Swindon has been so inextricably linked to what it became in the industrial sense, many people are surprised to learn that it is a very old settlement indeed.”

The books, meanwhile, just kept coming. He couldn’t help himself. From photobooks on Old Town and Central Swindon to a Hometown History: Swindon for children, and a string of studies on anything from the History of Barnes Coaches and the Swindon Water Company to Swindon Chinese Jazz Club 1960-1963.

Another pinnacle was achieved in 2013 with The Swindon Book, an exhaustive A-Z that took us from The Adastrians Drama Club to Yucca Villa in Bath Road. A glorious factual tome to dip into at leisure.

If that wasn’t enough, The Swindon Book Companion arrived in 2015 crammed – as publishers Hobnob aptly described it – with “a considerable amount of previously unrecorded material.”

Ever wondered who managed all of the 19th Century pubs of Swindon? Probably not. But in case you did they’re all here...from James Toe of the Artillery Arms to William Reed of The Wild Deer.

It bore all the Child hallmarks: diligent research, attention to detail and sheer hard graft aligned to unabated enthusiasm.

By this time Mark had sadly become ill and his wife Lorraine helped him finish the book which, like many of his works, are simply indispensable for anyone interested in the history of this town... be they current readers or those over decades to come.

- Mark Child is in all likelihood the greatest chronicler of Swindon’s history. There have been other significant contributors, however.

Swindon Advertiser founder William Morris in 1885 published the town’s first history, the quaintly written and even more quaintly titled Swindon Fifty Years Ago (More or Less) – Reminiscences, Notes and Relics of Ye Old Wiltshire Towne.

If it wasn’t for this important but – as Mark put it – “extremely flawed” book we would know even less about so many aspects of Olde Swindon, from smuggling and bear baiting to mummers and backsword fighting.

Tailor’s son Frederick Large’s Swindon Retrospective (1931) is an invaluable volume of personal recollections, from the day the “emancipator of Italy from slavery” Garibaldi received a tumultuous welcome in town to the triumphant return to Wroughton of locally-trained nag George Frederick after winning the 1874 Derby.

A century ago Alfred Williams, the Hammerman Poet, produced the seminal Life In A Railway Factory, recounting the harsh conditions inside the “Swindon Works”. “Undisputed as the most important literary work ever produced in Swindon, about Swindon,” is one appraisal.

Dave Backhouse’s Home Brewed, A History of Breweries and Public Houses in the Swindon Area (1984) followed years of dogged research that often involved delving into centuries-old deeds of properties that once sold alcohol.

Peter Sheldon has a string of publications to his credit since the 1970s including Swindon In Camera, Roadways, A Swindon Album and Fishing For the Moon – the latter making a highly plausible case for the Wiltshire Moonrakers hailing from Swindon instead of Devizes.

Son of Swindon Town football legend Billy Silto and one time skipper of the England table tennis team, retired GWR railway foreman Jo Silto in the early 1980s produced The Railway Town and A Swindon History 1841-1901.

Both are well worth seeking out via the internet – or, if you’re lucky, a local charity shop – as are several enlightening 1980s works by Trevor Cockbill that examine the pioneers of New Swindon.

- Struggling in April, 2014 to unearth information for a feature on a long-gone 19th Century Swindon pub called, at various times, The Union Railway Inn, Union Inn, Union Tavern or sometimes – just to confuse us – The Railway, an unsolicited email suddenly pinged in.

It was from Mark Child who had gotten wind of my fruitless endeavours to acquire the name and details of one of this establishment’s landlords that was crucial to the story.

“The chap’s name was Richard Bullen (1831-1907)” he wrote before supplying a detailed rundown of the man’s life, family and career.

“Born near Croydon, Surrey, and in 1867 married the widow Jane Annette Betteridge (nee Dixon), a Wantage girl, whose previous marriage to William Betteridge in 1860 had produced a daughter, Eliza Jane, in 1862...”

Where on earth did he find all this?

Clearly, a man who not only knew his stuff but was gracious enough to share it with the uninformed!

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel