IT is funny how a community that existed for hundreds of years, where generations had worked side-by-side in its fields and had lived, laughed and loved in their isolated corner of the lush Wiltshire countryside could simply vanish – snap – just like that.

Anyone walking along The Ridgeway, one of the world’s oldest pathways that skirts past Swindon on its 87-mile journey from Avebury to the Chilterns, may be surprised to learn that if they took a short detour from the escarpment near Aldbourne they would happen upon Snap.

Or rather, they wouldn’t – because even though its name still appears on the Ordnance Survey map and signposts to Snap exist there is actually nothing left of the buildings themselves, apart from a few stones poking through the undergrowth and the remnants of a leafy lane which once served as Snap High Street.

You can’t even call it a ghost village or a ghost hamlet because there is no village or hamlet left… although I’m sure that as dusk descends around its scattered trees it can get pretty spooky down Snap way for anyone with an imagination or a dram or two inside them.

The spot oozes “a peculiar melancholy which is often evoked by places which have been inhabited for centuries past but which are now deserted,” according to historian Kenneth Watts who 30 years ago published an account on the sorrowful demise of Snap.

Another piece, entitled ‘A Village Disappears – The Strange Story Of The Decline, Fall and Eventual Annihilation of The Hamlet Called Snap,’ appeared in Wiltshire Life magazine in October, 1967, recounting the settlement’s bizarre, unusual and somewhat abrupt downfall having survived almost 700 years of written history.

In a description especially relevant in ever expanding Swindon ten miles away, its author RS Turner wrote: “At a time when the building trade presents an unprecedented threat to the countryside it is fascinating and rather exciting to see a complete natural landscape where only 50 years ago lay a thriving hamlet.”

So what happened to Snap? It is a tale not without controversy or sadness and one that included a fuming MP, allegations of a landlord’s greed and a court case for slander.

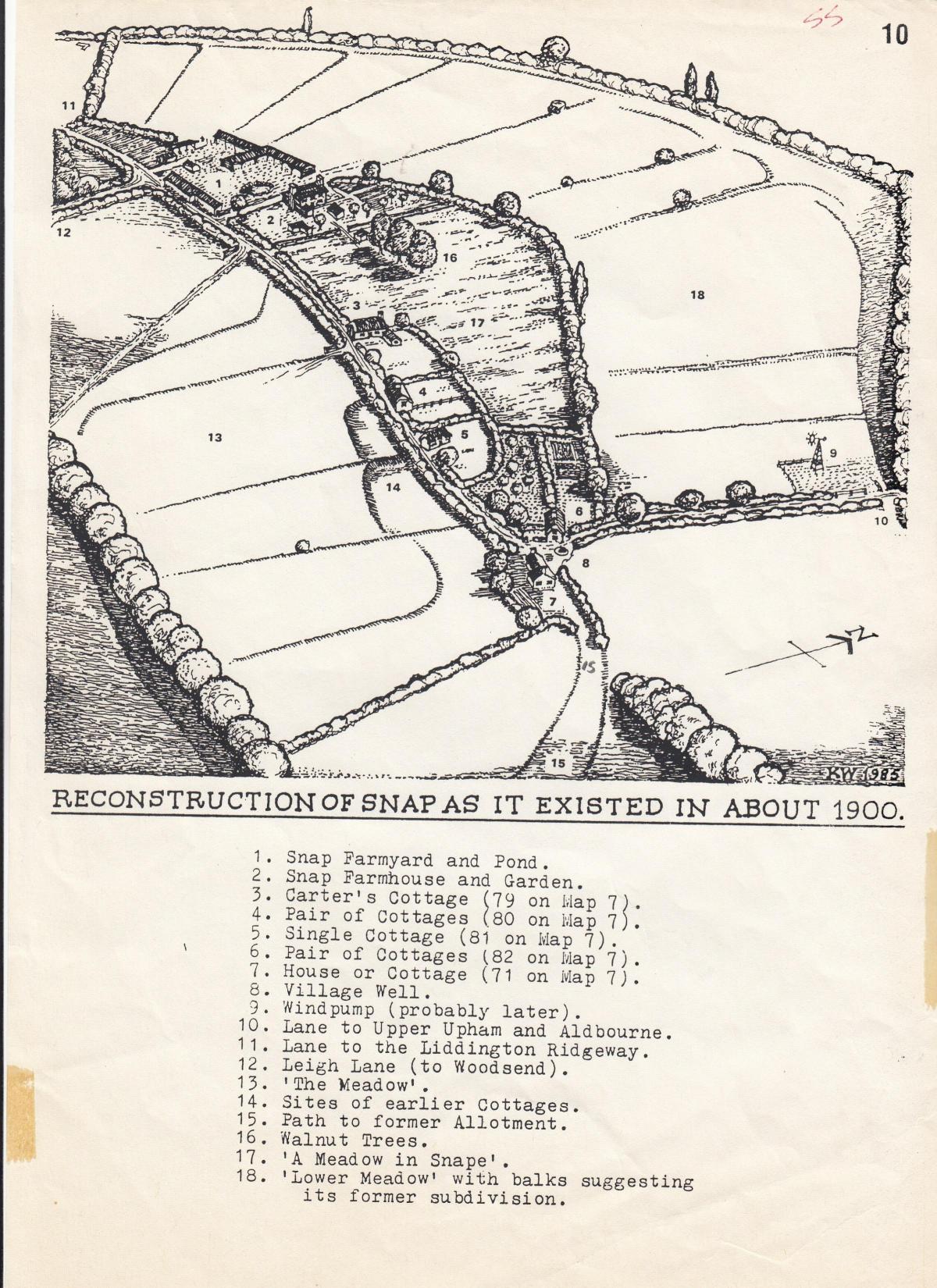

It was even subject more than 100 years ago of a Keep Snap Alive campaign by an outraged Daily Mirror a few years after the departure of the last ‘Snapites.’ Taking its name from “snaep,” which in Old English means “boggy place,” Snape was first recorded in 1268. Always a small settlement and located well off the beaten track, it housed 19 poll-tax payers in the 14th Century, while in 1773 Snape comprised up to ten cottages.

By 1841 there were 47 inhabitants – all earning a crust from the hamlet’s two farms – compared to a population of 2,495 in Swindon.

There was no other employment in Snape – no pub, church (though perhaps a small chapel) or school – though it did apparently have a windmill.

For centuries life in Snap continued pretty much unchanged with inhabitants working the land, their lives governed by the seasons, and living – we can safely assume – a tough existence in relatively primitive, rustic conditions.

The community’s days became numbered, however, with the 19th Century repeal of the Corn Laws which opened the floodgates for cheap American grain that seriously undermined Snap’s farms, along with countless others.

A string of bad harvests during the 1870s and ’80s fuelled the crisis, forcing many Snapites to seek employment elsewhere, including Swindon where a railway establishment was growing.

Snap’s population plunged from 53 in 1861 to 34 – just six families – in 1881. We still know the names of some of them: John Jerram, George Fisher, John Plumber, John Bates, George Ebsworth, James Fisher and Robert Fox.

And then, in 1905, controversy when Ramsbury butcher Henry Wilson snapped-up – sorry – the hamlet’s two farms to convert them from crop fields to sheep runs, depriving more locals of work.

The grim exodus continued. There was little to keep Snapites in Snap, home of their fathers, their forefathers and so on. A report in the County Newspaper early in the new century described the conditions of Snap cottages as “miserable.”

No work, decaying homes, overgrown hedgerows and crumbling walls – even rumours of the wells drying-up... Snap became a Dead Village.

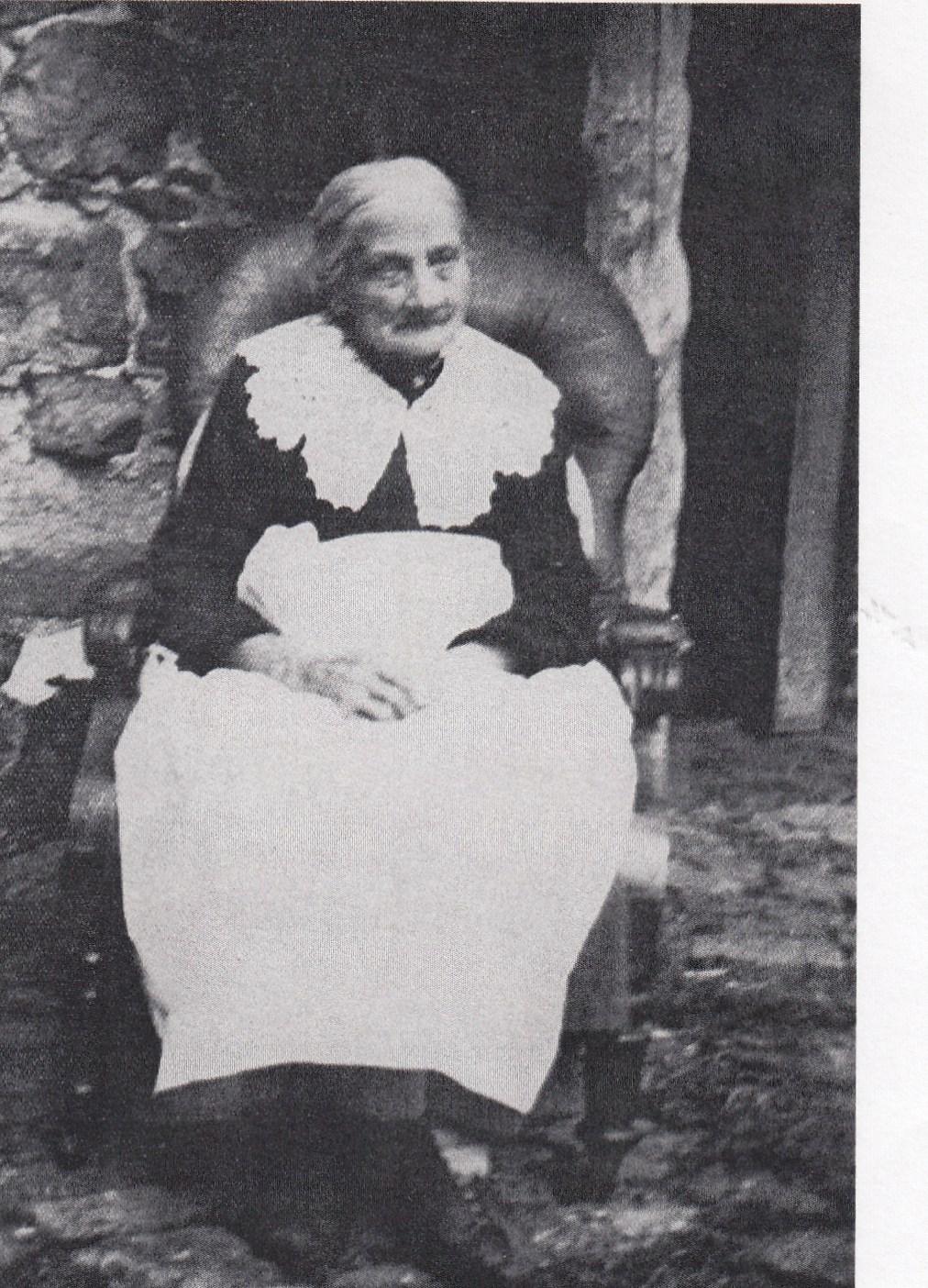

The last to leave was frail Rachel Fisher, who stayed on alone following the death of her husband, the aforementioned James. She died in 1910 aged 96, having a year or two earlier been given a home at Cook’s Yard, Aldbourne.

Fifteen years ago Rachel’s great grandson John Fisher, 75, of Aldbourne told the Adver that her reluctant withdrawal – even though she was the only soul left – was a huge wrench.

“Rachel didn’t like it in Cook’s Yard. She loved nature and she couldn’t hear the birds like she could in Snap. She missed the barking of the foxes,” he said.

Entirely abandoned, the ruination of Snap’s already crumbling cottages was further hastened in World War One when the derelict hamlet was battered and buffeted during military training.

In that way, it mirrored the fate of Wiltshire’s other “ghost village,” Imber on Salisbury Plain – the difference being that Imber folk were ordered out during World War Two and prevented from ever re-populating their ancient settlement after it was declared a permanent war games zone.

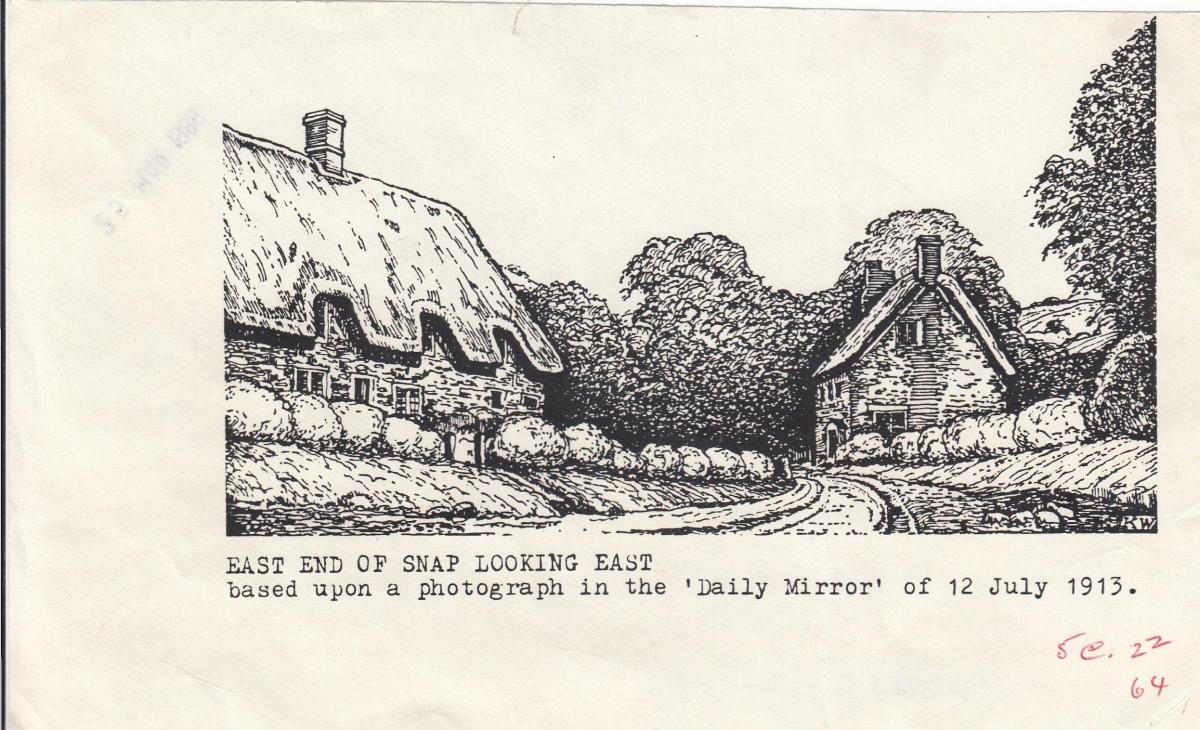

The only known photograph – or snap – of Snap is over 100 years old, showing its eastern end. With its thatched cottages and neat hedgerows it is an idyllic scene – but one that almost certainly masks the rural poverty into which it descended.

Today, the vanished hamlet is remembered in the name Snap Farm, while ruins of the “medieval village of Snap” are inscribed on the OS map.

If you kick around the site you’ll come across some rubble, most of the decent stone having long since been carted away as building materials. Fragments of cheap Victorian china, unearthed by moles, are occasionally found.

And if you take time drive to Snap along the tiny rural lane from Ogbourne St George, chances are that you will motor straight through it without noticing.

Unremarkable and largely unnoticed for almost its entire existence, it has been said that Snap is better known today than it ever was when it was alive, simply because it vanished…

- IMAGINE the excitement in sleepy Snap when the Civil War suddenly erupted on its doorstep.

The Battle of Aldbourne Chase in the summer of 1643 saw dashing Prince Rupert of the Rhine at the head of the Royalist cavalry swoop upon the Roundhead army of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex.

On their way from Gloucester via Swindon to London, the Parliamentarians with 1,000 sheep and 60 cattle in tow, hoped to avoid Rupert’s marauders by taking the little trammelled valley where Snap lies.

But “in a miraculous move” Rupert’s men hit them in the flanks and gave the Roundheads a duffing-up.

Minor stuff, really – but the Talk of Snap for years to come, I’d imagine.

- RADICAL MP for North Wiltshire Richard Lambert was in no doubt over the reason for Snap’s demise.

He was convinced it was cynically orchestrated by local butcher Henry Wilson who in 1905 bought the hamlet’s two farms and converted 8,600 acres of arable land into sheep farming territory.

In a fiery speech in Wootton Bassett in 1913 he said the people of Snap had been driven out by sheep, which required relatively few custodians.

When Wilson died, his sons sued the MP for slander – but lost.

In a 1970s guide to the Ridgeway JRL Anderson wrote that Snap was a “place that was deliberately abandoned to make more room for sheep.

“The dispossession of a few inarticulate peasants was not on a scale sufficient to pull the national heartstrings.”

Others, however, feel its demise was probably inevitable anyway.

- A FEW years after it was finally abandoned the Daily Mirror, intrigued at the hamlet’s fate, launched a campaign for Snap’s revival.

In reports that would shame the Mirror today it claimed that some folk were still actually living there.

One of these, Mrs Betsy Black was quoted as saying: “We live very comfortably in the chapel. We get our living by hawking (falconry?) or selling vegetables.”

He husband piped in: “It is very quiet now… nobody ever troubles us.”

Either by design or incompetence, the Man from the Mirror had confused Snap with neighbouring Woodsend.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here