“ON Sunday whilst the Sabbath bells were calling worshippers to divine service large crowds of Swindonians were wending their way towards Blunsdon to witness the widespread devastation created in but a few hours by that most destructive of foes…..the demon of fire.”

That’s how the Swindon Advertiser, then a weekly newspaper, dutifully recorded the dramatic aftermath of the historic events in April, 1904 before promptly adding, as if with an understanding shrug of the shoulders: “And who could blame them.”

On this bright spring morning when “the sky was a lovely expanse of pure blue,” as we poetically put it, there was only one thing on the minds of many Swindon folk.

In the days when television wasn’t even science fiction and the world’s first radio news broadcast was still two decades away, word of the grand calamity had spread through the grinding, noisy engineering shops of the Great Western Railway Works and the bustling bars of Swindon’s taverns.

The lure proved irresistible for many and by Sunday, April 24 – two days after the first flames were spotted – people were swarming through largely untampered countryside which today houses the urban sprawls of Pinehurst, Penhill and Abbey Meads.

“Nearly the whole day vehicle traffic, traps, bicycles and motors” passed along bumpy rural lanes to tiny Blunsdon St Andrew three to four miles away, we reported. However most of them – including the Advertiser’s correspondent – walked.

They were all eager to witness the smouldering remains of what this newspaper described as “one of the most serious conflagrations that has ever been recorded in the county.”

Such was the volume of sightseers that 25 Bobbies were deployed to hold them at bay.

Like the tramcar tragedy of 1906 when a packed conveyance skittled down Vic Hill killing five people and seriously injuring many more, the Blunsdon Abbey inferno, which reduced the once palatial house to the skeletal ruin it remains today, was a great Swindon disaster of the Edwardian era.

Today the derelict mansion, with its sporadic clumps of picturesque ivy, stands with Holy Rood in Old Town among the borough’s few “romantic ruins.”

I am reminded of Blunsdon Abbey by the news that long awaited proposals have finally been revealed to build a new Blunsdon Abbey – the other one where speedway and greyhound racing take place.

That, and an email from Louisiana (see panel) concerning the antics of some of the first “helpers” on the scene 112 years ago.

The once impressive country pile was built in 1864 on the site of an outpost of medieval Godstow Nunnery that is located on an island in the Thames near Oxford – hence the Blunsdon Abbey moniker.

Following Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, the land passed to the Brydges family, prompting Sir John Brydges to build a spacious abode that in the 17th Century was described as a “faire Gothique house with a great hall after the old fashion.”

That’s exactly what it was - old fashioned - when it was acquired in 1860 by wealthy sportsman Joseph Clayton de Windt who demolished the lot and commissioned Swindon builder Thomas Barrett to create ”one of the finest homes in the West of England.”

No expense was spared in raising a fashionably neo-Gothic style residence which boasted 40 bedrooms and grand interiors while a large lake and boathouse were fashioned within the estate’s 80 acres for good measure.

Poor de Windt never got the chance to impress his pals with his Grand Design as he toppled from a nag with fatal consequences in 1863 – a year before his Barrett home was finished.

A man called John Lyall swiftly snapped it up and after his death in 1880 it fell into the hands of Miss Louisa Thomas who dined there on the evening of Thursday, April 21, 1904 before departing for her London home.

The blaze erupted early next morning and was so brisk that a young girl was forced to plunge into a blanket clutched by adults below while others, hastily aroused in their nightclothes, made a clamorous exit via an improvised ladder.

“The whole place had been thrown into a state of excitement unparalleled in the annals of the peaceful and ecclesiastical seclusion of Little Blunsdon,” we reported. Before anyone had time to react from their slumbers “the elegant Blunsdon Abbey was in the throes of a furnace of heat.”

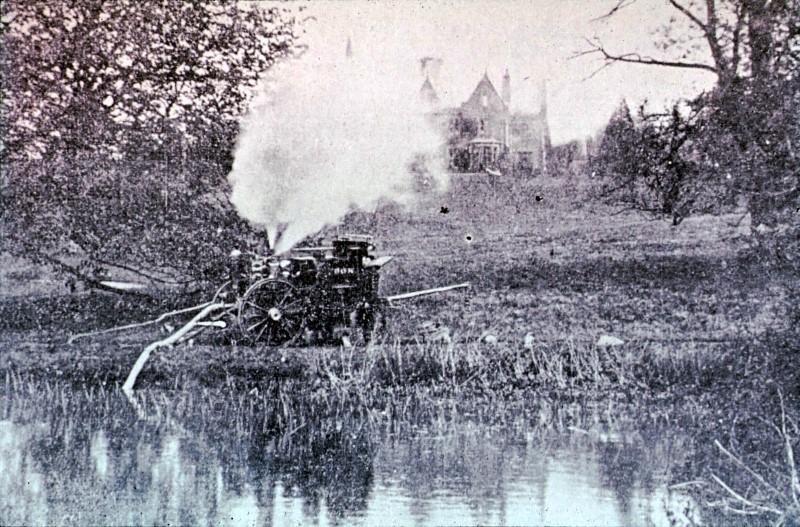

Fifty minutes after the alert was sounded by three workmen at 4.40am, Swindon Fire Brigade arrived and determinedly proceeded to pump countless gallons of water onto the conflagration from the man-made lake.

A fine photograph exists, which George Cox of Gorse Hill Post Office - who presumably took it - turned into a postcard showing the brigade’s trusty steam powered appliance almost at bursting point as it frantically relayed water to the beleaguered mansion.

For 15 hours the brigade, led by Captain Pritchard and Deputy-Captain Munday, fought to save the illustrious property but couldn’t prevent it from being reduced “well-nigh to cinders with nothing scarcely but the black walls standing.”

Wind and fire, we added, “conspired to defeat the onslaught of water” to such a point that “even to the most indifferent observer it was evident that Blunsdon Abbey was doomed….”

- THE estimated cost of Blunsdon Abbey’s devastation was put at £30,000 - nearly £3.5 million today. However, you’d have to stick at least an extra nought on the end if a similar pile went up in flames tomorrow.

Several “priceless” works of art were lost including paintings by the celebrated Dutch school and Turner’s Grand Canal Venice.

Lace once owned by Marie Antoinette, a silver candelabra said to have belonged to Napoleon, some unique china and a much prized collection of books also went up during the “swift awful reduction of grandeur,” as we put it.

The fire was probably caused by an electrical fuse that ignited the impressive drapes in the dining room.

Although insured, it was decided not to reconstruct the abbey around its fire scarred shell. Around half-a-century later the ruined site became home to Blunsdon Abbey Caravans.

Today the structure’s remains form an attractive centrepiece for a secluded “park homes” style development just north of the far-reaching tentacles of the Abbey Meads housing behemoth which, of course, takes its name from the once grand Victorian mansion.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here