LIMP-wristed, vapid, wishy washy, irresolute – Alexander Keiller was none of these. When he decided to do something he threw himself into it with a fervour and spirit that bordered on obsession... be it women, witchcraft, ski-jumping, the dispatch of alcohol or the hunt for the Loch Ness Monster.

When his ardour turned to sports cars he amassed one of the finest collections of the era, employed a team of mechanics and drivers to race them, and built a factory to make them.

He helped pioneer aerial photography and during a spell as a Wiltshire Police Inspector became an acknowledged expert in the refined field of fingerprint technology.

But for sheer, unfettered zeal nothing quite matched Keiller’s passion for archaeology.

It is hard to imagine what our local World Heritage Site, the 5,500 year-old Avebury Stone Circle complex would look like today – if it actually existed in any recognisable form – but for Keiller.

Or indeed, but for marmalade... because little of the above could have happened without the assistance of that ever popular breakfast preserve.

It is fair to say that if Alexander Keiller’s great-great-great grandmother Janet hadn’t dabbled in marmalade-making more than 200 years ago then it is unlikely that 350,000 visitors would wend their way to Avebury every year to immerse themselves in the site’s magic and mystery.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of a lasting gift to the National Trust – and thus to the People of Britain – by Keiller’s fourth wife and widow Gabrielle… a 17th Century barn that her late husband founded as a museum/research centre.

Today The Alexander Keiller Museum –one of the finest in Wiltshire – stands alongside those mighty megaliths as a lasting monument and tribute to The Man Who Re-Built Avebury.

Let’s go back to late 18th Century Dundee – the day when Janet decided to boil up some newly-squeezed orange juice with sugar and water in time-honoured marmalade-making tradition. And then, perhaps on a whim, she chucked the rind in too.

We all know about marmalade with “bits in” but it was Janet who did it first – suspend the rind in the preserve.

It went down a treat and in 1797 led to the foundation of James Keiller & Son that produced what is believed to be the world’s first commercial brand of marmalade. By the late 19th Century, Janet’s chunky preserve was being exported all over the world.

Which was very good news indeed for her great, great, great grandson Alexander who in 1910 inherited the business at 21 to become a Marmalade Millionaire.

Marmalade, however, wasn’t his bag. He much preferred girls, action, fast cars, booze, adventure, sport, more girls – and also archaeology.

Leaving his uncle to make the marmalade and the money, Keiller set off to study the stone circles near his home in Morven, sparking a life-long interest in prehistory.

Also an enthusiast of sleek, racy cars, he founded the Sizaire-Berwick auto company in 1913 as well as assembling his own sparkling collection of shiny four-wheeled beasts.

When World War One arrived, the Sizaire-Berwick chassis became a key component for a new breed of military vehicle – the armoured car... and Keiller was commandeered to drive several of them through the blitzed landscape of France.

Invalided out in 1915, he joined air intelligence in the nascent RAF who taught him a very useful trick – how to fly.

After the war this enabled Keiller to study the West Country from above, resulting in a still renowned book that he published with eminent archaeologist OGS Crawford, Wessex from the Air.

Blessed with the dashing good looks of an Errol Flynn/David Niven – and a handsome wad to match – Keiller notoriously acquired a string of girlfriends, wives and mistresses.

His less-than-chaste behaviour was further shrouded in rumours of sadistic sexual practices and rituals, spiced with hints of bisexuality (gosh!) It being the Roaring Twenties he swigged champers and cocktails with characteristic verve. Once, he and 16 guests downed 150 cocktails between them during a pre-dinner binge.

Nothing, however, obsessed him more than Avebury. His excavations at Windmill Hill, part of Avebury’s magnificent, though then largely-hidden Neolithic landscape, began in the early Twenties.

When Marconi wanted to erect a telegraph station there Keiller promptly stuck two fingers up at them and bought the land.

Encouraged by a wealth of discoveries he set about re-creating Avebury’s once imposing West Kennett Avenue ceremonial way, where less than a handful of the stones survived upright.

Then he cast his eyes to Avebury itself which – despite acknowledged as an important archaeological site – was very different then than it is now.

Homes, farmhouses and barns proliferated in the heart of today’s grassy monument. Few of the greyweathers we see now were visible.

Some of these heavyweight sarsens had sadly vanished forever, having been carved up and used for building materials.

Others had long since toppled over and been buried either by farmers or superstitious Christians – or had simply vanished beneath the undergrowth.

Rightly convinced that this rich prehistoric complex could be revived, Keiller in 1934 snapped up almost 1,000 acres of Avebury and, employing an army of local workmen, set about one of the most ambitious heritage projects ever mounted.

His aim? To restore a once magnificent Neolithic site as near as dammit to its golden era 4,000 or so years earlier.

Many cottages and farm buildings within the Great Henge – the huge ceremonial bank and ditch that encircles the complex – were demolished. Fences were removed, trees dynamited, undergrowth cleared.

Thousands of tons of rubbish that had accumulated over the millennia was scooped out of the barely visible ditch.

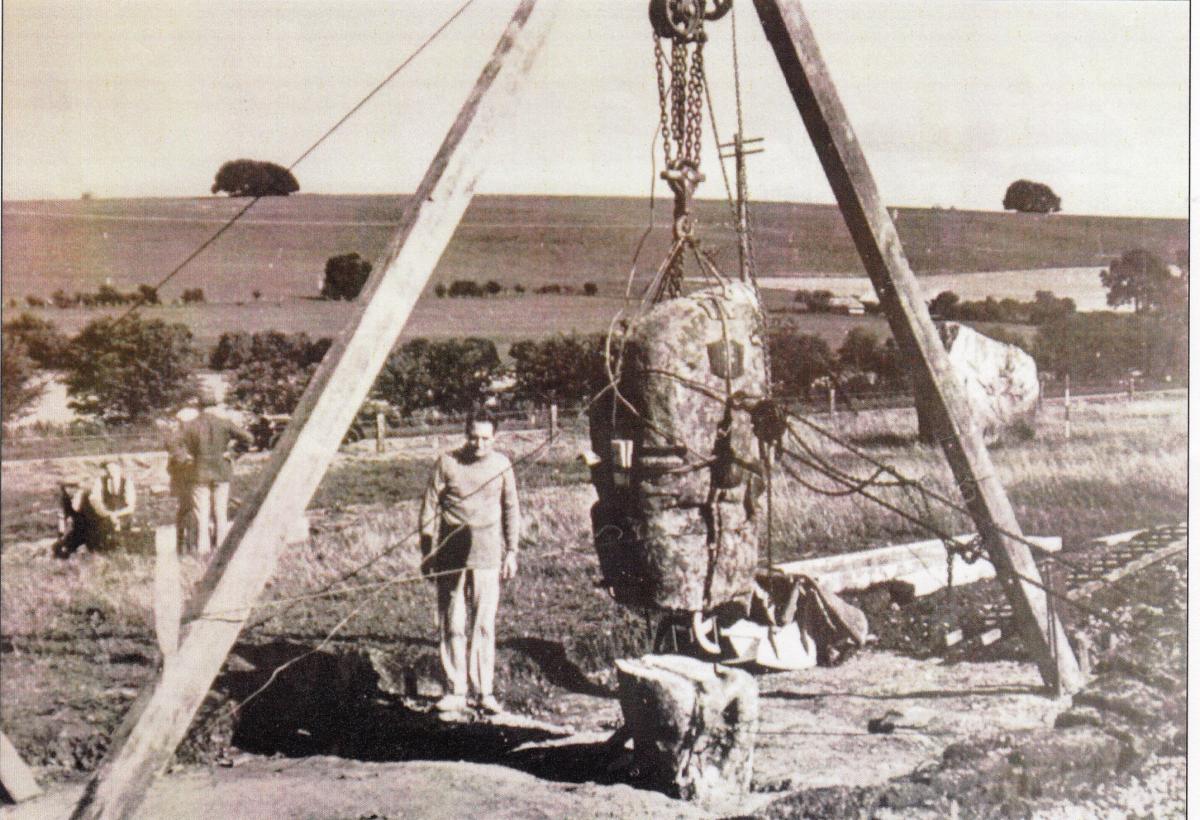

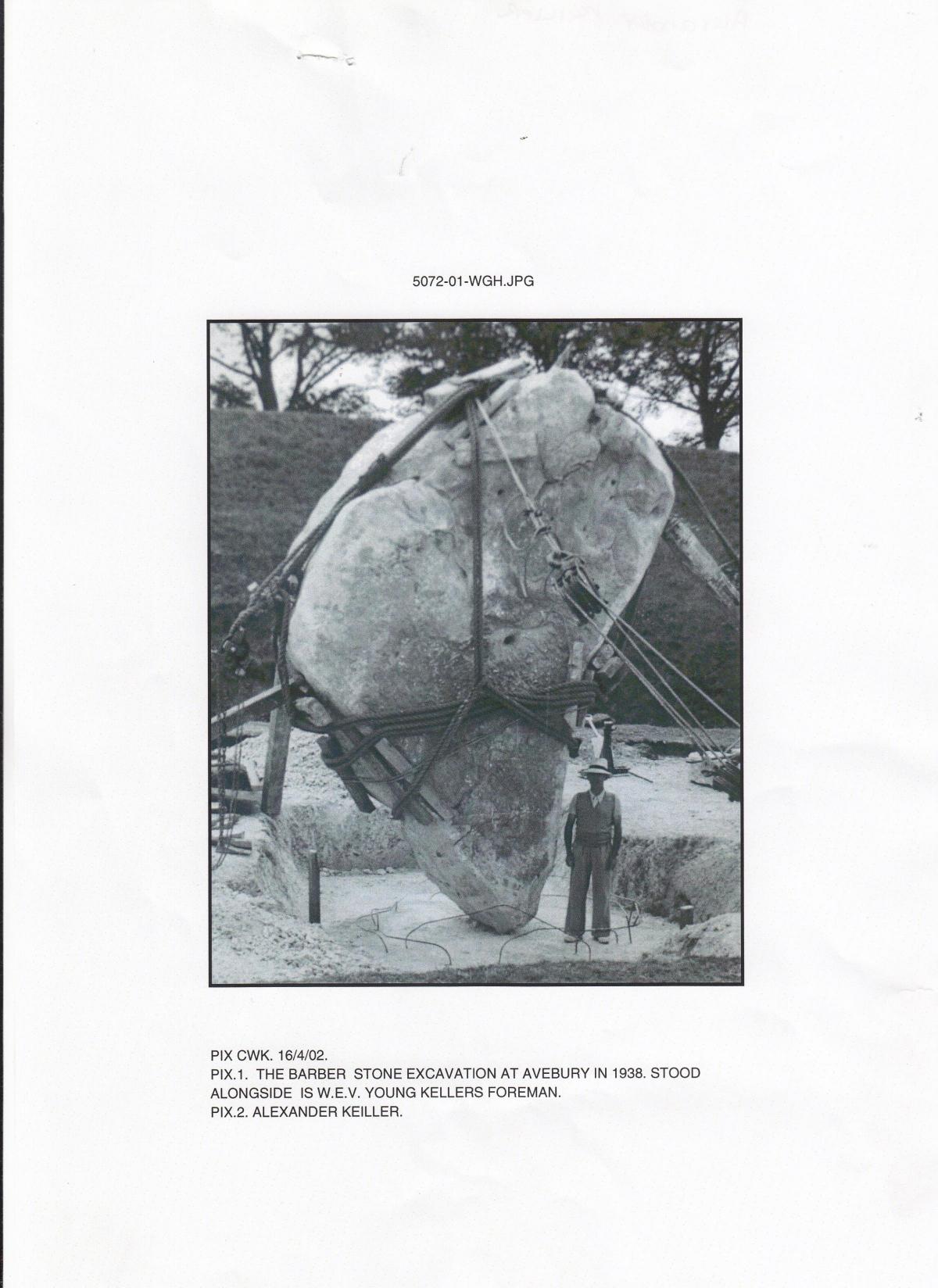

Giant grey sarsens – some more than 60 tons – were unearthed, hoisted up and grandly positioned in their original stone holes before being set in cement.

Modern homes were built at nearby Avebury Trusloe to re-house those displaced –though not, apparently forced – from the henge.

It is unclear how far Keiller actually intended to go – was his ultimate aim to remove every form of human habitation from the henge... pub, church, post office, the lot?

We’ll never know because Hitler intervened and the dramatic Re-Building of Avebury came to an abrupt, inconclusive and final halt. Plagued by ill-health Keiller later sold the land to the National Trust at a knock-down price before succumbing to cancer at 66 in 1955.

Avebury remains pretty much as it was when Keiller’s workforce downed tools around 75 years ago – a unique community existing quirkily and eerily within the world’s largest prehistoric henge that is dotted with spectacular megaliths a large number of which had been re-erected in the 20th Century.

And for this we can thank Alexander Keiller... along with his great, great, great grandmother’s marmalade.

- JANET Keiller’s marmalade is said to have been the world’s first commercial brand of the preserve.

James Keiller & Son is also credited with being the first company to make and market the famous Dundee Cake.

Alexander sold the firm to Cross & Blackwell before it was eventually acquired by another famed Scottish producer of preserves, Robertson’s.

One of Janet’s great-great-great-great grandsons is the British TV presenter Monty Don.

- WHEN Wootton Bassett-based historian Lynda Murray in 1999 wrote a book about Alexander Keiller she aptly called it A Zest For Life.

His exploits included:

Acquiring an extensive and varied selection of books about witchcraft, demonology and devil-lore.

Bankrolling an expedition to track down the Loch Ness Monster.

Being voted President of the Ski Club of Great Britain and financing the building of two ski jumps near St Moritz.

Becoming a skilled marksman.

Studying criminology which, during World War Two as a Special Police Inspector at Marlborough, led him to become an expert on fingerprints.

Discovering in 1938 the now famous medieval skeleton, The Barber Surgeon of Avebury, beneath a buried megalith, complete with 14th Century coins, a pair of scissors and a medical type robe.

Founding nearly 80 years ago an Avebury research/display centre that is now the museum which bears his name.

- YOU could hear a pin drop down at The Red Lion as a “home movie” flickered to life to provide a fascinating glimpse into a vanished Avebury – the one that existed before Keiller.

Rediscovered in a biscuit tin in 2000, almost 50 years after it was last seen, it was filmed by villager Percy Lawes between 1937 and 1939.

It showed around 20 houses that Keiller demolished as part of his reconstruction of the Avebury stone circle complex.

Among those watching, Jane Lees, 72, said: “Three quarters of the village was torn down to make way for the stones, including many beautiful cottages.”

The newer homes where they were re-housed at Avebury Trusloe, though, had mod-cons – including electricity.

Keiller, who lived at Avebury Manor, was generally liked in the village despite levelling so many of its houses. He was, to quote one of his neighbours: “A rogue, an eccentric and a great ladies’ man.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel