ON the edge of a secluded valley, with its pretty woods and pond, Frank Hunt utters a short, shrill whistle. We both crane our necks and gaze expectantly at the bright early evening sky. Complete silence – where could she be?

Several seconds later, without warning or noise she appears from behind a high, partially crumbling wall: beautiful, majestic, powerful, very fast but swooping at us seemingly without effort.

The one year-old Harris Hawk, with its two-foot wing span, touches down with incredible delicacy on Frank’s leather gloved left hand. Her eyes are sharp and alert; her chestnut plumage immaculate. “She lands very nicely,” says Frank, with some satisfaction.

The scene reminds me of a memorable description in Barry Hines’ 1968 novel A Kestrel for a Knave – later filmed by Ken Loach as Kes – when inarticulate Billy Casper suddenly stumbles into poetry.

Flicking through my Penguin paperback edition an hour or so later Billy’s words could hardly have mirrored the episode I had just witnessed with greater accuracy.

“You ought to have seen her,” he tells his classmates. “She came like lightning, head dead still, an’ her wings never made a sound, then wham! Straight up on t’glove, claws out grabbin’ for t’meat. I wa’ that pleased I didn’t know what to do wi missen.”

This, however, is not the South Yorkshire countryside on the outskirts of Barnsley where Hines’ story is set. We are on the edge of Chiseldon, about half-a-mile from the M4, although you’d be hard pressed to guess it. Frank is giving me a taste of his woodland “hawk walk” – one of several birds of prey packages he has devised after bringing the ancient sport of falconry to Swindon.

He runs the Wiltshire Falconry Club from the Butts Business Centre, within the shadow of Chiseldon’s ancient Grade One listed Holy Cross church. The aim is to give people in and around Swindon the opportunity to experience falconry, which is the art of training and hunting with birds of prey.

Says Frank, 25: “We are the only falconry club in Wiltshire and are offering a chance for people to enjoy a sport that is quite often out of their grasp – both in terms of expense and distance.

“At the moment anyone from this area who would like to learn more about birds of prey, see them fly at close quarters, or learn how to handle them, has to travel some distance. Here, we are just a few minutes’ drive or bus journey from Swindon.”

Surveying the sweeping rural surroundings he adds, without really having to: “When you get out here, though, you are in the countryside.”

Former Ridgeway school pupil Frank, who has lived in Wroughton virtually all his life, saw his first bird of prey when he was six or seven; graceful, strong, almost stately, not to mention a little unnerving. It made quite a mark on the youngster.

It happened when his parents Dave and Caterina took him to what was then the National (now International) Centre for Birds of Prey at Newent in Gloucestershire.

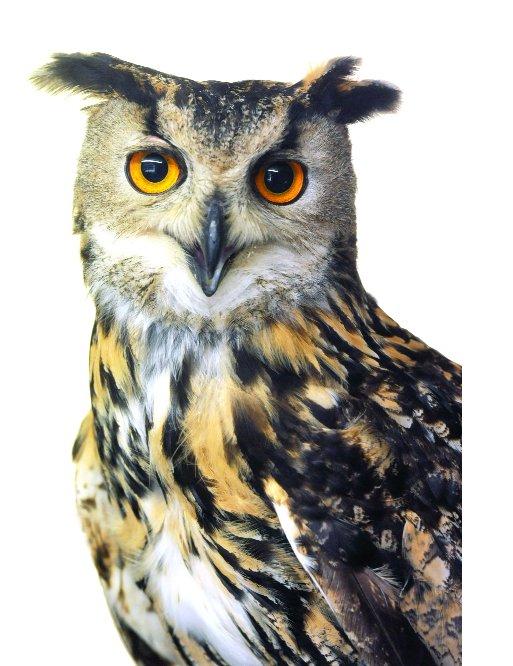

He says: “I remember seeing a European eagle owl in a flying display there. It was incredible; a hugely impressive bird. Even at that young age I could see what a beautiful thing it was. “I had never seen anything like that before – especially in flight. I was able to have it on my arm, but it was so heavy my dad had to support my arm.”

Fired with enthusiasm for birds of prey, his grandfather Jim Hunt, who still lives in Wroughton, bought him a book, A Hawk in the Hand by Phillip Glasier, which became a sort of bible for young Frank.

He says: “I must have read it about 100 times. It told me all about falconry. It kept me going in between visits to the birds of prey centre. It really helped keep the interest alive.”

It soon became obvious to Frank that falconry wasn’t just a fad; he was fired with a true passion for it. When he was 16 Frank spent six months, five days-a-week working at the centre in Newent, learning as much as he could about assorted birds of prey from experienced falconers.

He became a landscape gardener by trade – and still is – but now owns three birds of prey. He began giving displays for guests at Chiseldon House Hotel as well as appearing at local events such as fetes, displaying his growing skills as a falconer.

He has now acquired a unit at the Butts Business Centre, enabling him to launch the Wiltshire Falconry Club. He says: “I feel I am now in a position, financially, to do it – to run a club and give tuition.”

The club offers a variety of falconry related experiences, for individuals or groups. Its small group of members range from men and women in their 40s and 50s to a 15 year-old boy. Membership is available to would-be falconers from 13. Frank goes on: “We are offering people the opportunity to fly a selection of birds of prey unsupervised once they are competent and confident enough to do this.

“Now the weather is improving we’re expecting to be busier. The birds fly in all weathers, but people don’t generally come out when it’s so cold.”

When Frank says “we,” he really means himself, occasionally aided by his girlfriend, Stephanie Bryson, 19, who helps out.

Frank’s trio of birds – all female – were acquired for between £300-£500. Entering his falconry unit, visitors are greeted with the awesome, imperial and somewhat intimidating sight of Boomer, with her huge, knowing bright orange eyes. She flaps her mighty, magnificent wings with their four foot span and makes a strange, deep, squawky sort of sound; she booms – hence her name.

Five year-old Boomer is a European eagle owl, the world’s largest and most ferocious owl. Stunning and a wee bit scary, she is a truly imposing creature.

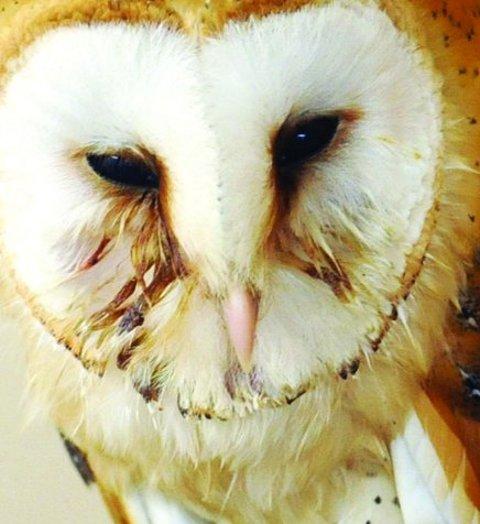

By contrast Tilley, aged three, who occupies the next cage, is a real cutie. With her heart-shaped, mask-like face she looks almost unreal, like a finely detailed painting.

Both owls are used for “post work” – which means flying from post to post. The aforementioned Harris hawk is so far nameless. “I haven’t decided what to call her yet. There have been a few suggestions – Storm, Flash – but I’ll wait till I come up with a more suitable name,” says Frank.

She is the star-turn in his woodland hawk walks, which involve showing guests how to fly a hawk as they make their way for half-a-mile or so through the attractive countryside adjoining The Butts.

It is at this point, as we amble along a track leading to Washpool Woods that the hawk vanishes from sight, prompting concern on my part, but a smile on Frank’s. “She disappears but never really goes that far,” he says.

As if to prove a point, the raptor returns with an almost regal flourish, and is rewarded with a chunk of meat which Frank produces from his pocket. “She always keeps an eye on me. I couldn’t lose her, even if I ran off.”

- The Wiltshire Falconry Club’s woodland ‘hawk walks’ from its base in Chiseldon are available at £15 per person. Group tickets can also be booked.

Frank offers morning or afternoon falconry experiences, with lunch available at £65 for two or £95 for a group ticket of up to four people with lunch at the nearby Patriot’s Arms pub.

Frank can be contacted 07583-478201. The club’s Facebook page can is at: wiltshirefalconry.club@facebook.com

Hunting Out The History

Falconry is the hunting of wild quarry in its natural state and habitat by means of a trained bird of prey.

Evidence suggests that it began in the Middle East around 4,000 years ago.

Falconry became a popular sport and status symbol among the nobles of medieval Europe.

In the UK and Europe it probably reached its zenith in the 17th century before firearms became the tool of choice for hunting.

The UK saw resurgence in the late 19th and early 20th century when several falconry books were published.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here