A FLIMSY cordon of police is greeted with jeers, chants, the waving of placards and the shaking of fists along with the unmistakable sound of shattering glass, recalls BARRY LEIGHTON. It is a drizzly night in Swindon where anger, contempt and frustration, along with a hint of violence, fill the chilly air.

Suddenly, The Thin Blue Line wavers and is breached as the hoard shoves aside some helpless bobbies, bursts through the sturdy oak doors and heads with unwavering purpose towards a gathering of people to vent their collective displeasure and maybe chuck a few missiles.

By and large, council committee meetings are staid, humdrum affairs, enlivened by occasional sneers or insults exchanged between members of opposing political allegiances. Fairly civilised stuff, on the whole, if a tad tetchy and schoolboyesque every now and then.

Journalists dispatched to cover such events – and I’ve been to more than I can possibly guess - often find themselves doodling away in their notebooks, gazing into space or taking sly, intermittent peeks at the clock.

But quarter of a century ago a meeting of the Thamesdown Borough Council’s policy and resources committee in the council chamber at Swindon’s civic offices was not so mundane. The polar opposite, in fact.

It descended, as the Adver succinctly described it the following day, into “unprecedented uproar,” scenes of which had never been witnessed in such surroundings – Swindon’s very civic heart - before or since.

It was, to misquote The Sex Pistols, Anarchy In Euclid Street.

But what caused such rowdy goings on. What inflamed such passions? Why did the Adver brand it ‘Mob Rule.’ Anyone who was there that night, either inside the civic offices or among the hundreds assembled outside, will be able to tell you.

It was Margaret Thatcher’s infamous, divisive, ill-conceived and ultimately unworkable poll tax.

It is the 25th anniversary of those heady weeks in March and April, 1990 when every local authority, regardless of political affiliation, was legally obliged to set the amount of poll tax they would charge their residents for the coming financial year.

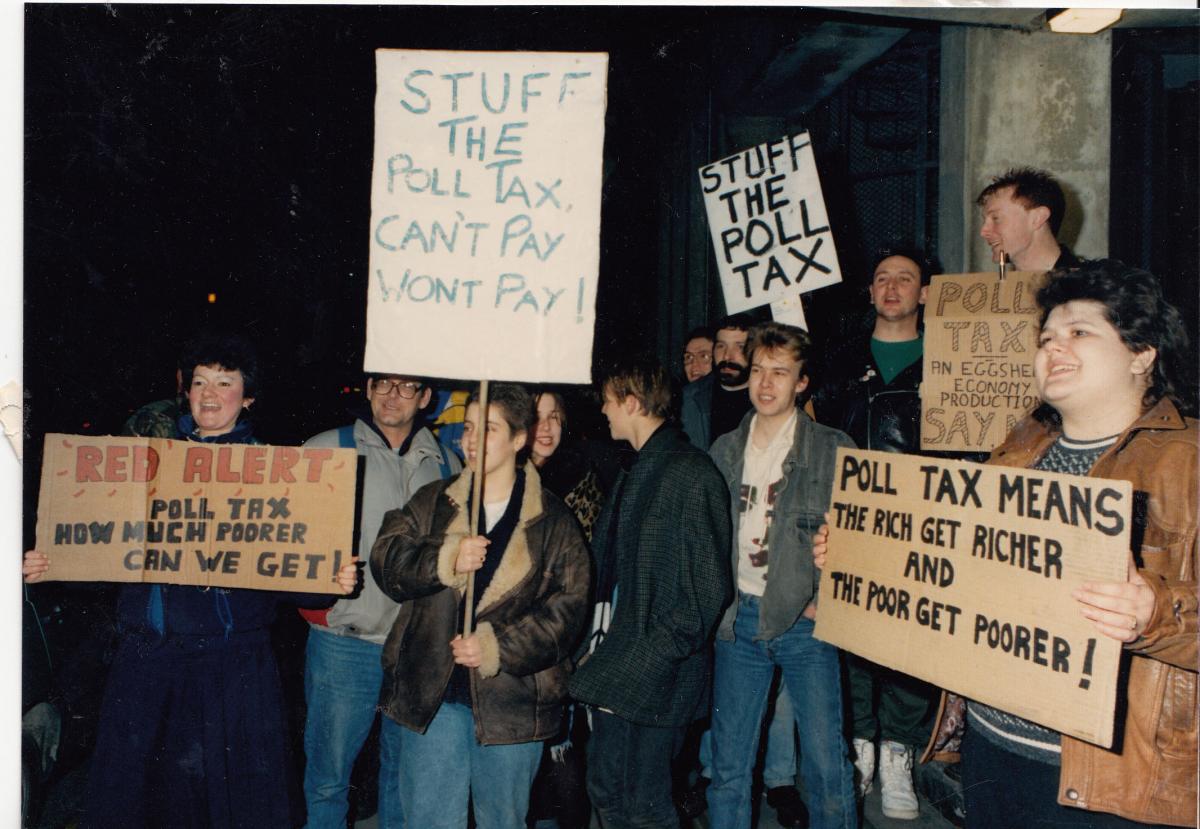

Unrest swept the nation. Communities were in commotion. Demos were widespread. There were riots going on. And Swindon was no exception. Indeed, it outdid itself.

As Thamesdown’s crucial policy and resources meeting approached Swindon’s Anti Poll Tax Union had distributed 4,000 leaflets to ensure a healthy turn-out whereby the public could exercise its democratic right to protest.

It’s 6.45pm-ish and around 1,000 people – normal, everyday working-class folk, mostly – mill outside the civic offices with their chants: “Maggie. Maggie, Maggie, out, out, out”.

They want to hear the debate inside but the chamber is rammed, the doors to the civic centre are slammed shut, and the proceedings are relayed via speakers.

I have attended some fairly feisty Swindon Council meetings over the years: those which saw the vote to close of three local schools in one fell swoop and the one during which the beloved Front Garden was designatednthe town’s next expansion zone both spring to mind.

But they are kid gloves compared to this…

At a minute passed seven, as the meeting gets underway, the doors to the chamber spring open and around 50 protesters flood inside bawling: “We won’t pay the poll tax, la la la la…”.

In the hot seat – and its roasting tonight – Council Leader Tony Huzzey is trying to make himself heard above the din and chaos. Old school Labour, he loathes the poll tax with a passion.

Such was the Labour administration’s contempt for the levy that they named Swindon’s impressive new civic hub after the leader of the 14th Century peasants’ rebellion against poll tax, Wat Tyler.

But tonight the mob are calling for Huzzey’s head, along with those of the other ten Labour, four Tory and two Democrat councillors. They don’t seem to care who’s who. Setting the tax would be endorsing it, they bellow. Simple as that.

Huzzey is shouting: “We don’t want this tax. We take no pleasure in tonight’s procedure,” but he is drowned out. “Resign,” people scream at him.

The meeting, as such, is finally underway at 7.22pm but the proceedings are inflamed, noisy and shambolic. And then, at 7.48pm, the doors are once more flung open…

Seconds earlier around 70 protesters had smashed their way through police and into the Civic Offices.

Barging into the meeting, they are swarming like wasps, jumping onto the polished rows of members’ tables, scurrying around the aisles, screwing agenda papers into balls and throwing them around.

The disconcerted members of Thamesdown Borough Council are engulfed by the rabble.

The silver-haired Huzzey, however, commendably holds his nerve as the place resounds with shouts, chants and general mayhem. Flanked by a council of wide-eyed security men he is trying to restore some sort of order. Some hope.

The council chamber resembles one of those boxing rings when scores of spectators pile haphazardly in at the conclusion of an important bout.

I am reporting these extraordinary goings-on for a regional newspaper while the Adver’s representative is municipal reporter Bill Beckett.

Bill covers council meetings all the time and it would be fair to say that during such occasions his thoughts have a tendency to drift towards The Beehive and how many he can get in before closing time.

Not tonight, though. We are gaping in astonishment from the press table as the events unfold almost surreally in front of us, all the time furiously scribbling notes while trying not to miss any of the action. It’s riveting stuff.

Somehow, amidst the disarray and confusion, a vote is taken and Huzzey announces into his mike, to the surprise of pretty much everyone: “The poll tax has now been set.”

Afterwards Tony Huzzey, shaken but not stirred, told the Adver: “We had the perfect opportunity to put our case (against the poll tax) and those stupid bastards ruined it all.”

This is how Bill summed it up: “In 30 years of reporting, during which I have covered the troubles of Ulster and the horrors of the Israeli-Arab conflict, I have not experienced a more vivid manifestation of that raw, human emotion – naked anger.”

- Around 40 police held firm…

“We’ll be back” pledged protesters, Schwarzenegger-like, as the meeting disintegrated in disarray. They were, too – but so were Swindon Police.

The agreed settlement of an average of £336 per person had to be ratified at a full meeting of the council the following week.

Around 800 protesters surrounded the Civic Offices where police officers were pelted with eggs and stink bombs and dummy bombs were let off.

Police claimed that an anti-poll tax tekky had even tried to block their communications with a radio jammer.

A hardcore group of 30 or so protesters tried to emulate their previous success and storm into the building.

But around 40 police held firm… their blue line a lot less thinner than the week before when just 14 officers were present.

- 'That was rent-a-crowd'

THE aftermath of the Invasion of The Civic Offices saw police blame outside activists while council leader Tony Huzzey exclaimed: “I hesitate to use the word but that was rent-a-crowd.”

However, Swindon anti-poll tax campaigners claimed they were local protesters venting their anger.

Four people were arrested – two at each council meeting – and one of them, from Oxford, was later jailed for four months for violent disorder.

Far and away though, the protesters who gathered outside the council offices on both occasions were everyday Swindon folk with genuine fears that their quality of life would be seriously reduced by this “iniquitous tax.”

The Adver spoke to many of them including Nellie Gibbs, 62, from Penhill, who said: “I am definitely not militant but I feel like killing Mrs Thatcher.”

- The Community Charge was abolished in 1992

COMMONLY known as Poll Tax, the Community Charge replaced a rates taxation system in England and Wales in 1990.

Changing from a payment based on the worth of one's house to a tax on every adult, it was widely criticized as being grossly unfair on the working and lower classes.

Introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government, it triggered nation-wide protests and riots.

The tax it proved unworkable and created numerous administrative and enforcement difficulties.

Legally obliged to set the tax, councils were also burdened with pursuing large numbers of defaulters - many acting as part of an organised resistance.

The Prime Minister’s popularity plunged as a result of poll tax and she was eventually forced to resign.

The Community Charge was abolished in 1992 in favour of Council Tax – which was just like the old rates system.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel