THE sky is blue, the sun is shining and I’m off to the pub. It’s The Plough at Wanborough for a lunchtime snifter and a hunk of cheese. But who’s that sitting on top of a roof in a shiny red hard hat? Good gracious, it’s a thatcher and he’s working on a brand new house.

Screeching to a halt, I am side-stepping cement mixers, stacks of freshly-baked bricks, small hillocks of sand and sacks of cement before craning my neck and bellowing up from the bottom of a ladder. “Excuse me mate…”

My journalistic tendencies have gotten the better of me. Luckily Mark Rumens is happy to talk. It’s time for his cuppa, anyway. He is a master thatcher and from his lofty position is planting “a top hat made of straw” onto a five-bedroom detached house.

Twelve weeks he’ll be up there, embedding 2,500 bundles of golden coloured Hungarian water-reed onto scores of battens – wooden strips of timber attached to the rafters.

Great to see traditional crafts thriving near Swindon, I enthuse as we chat about his age-old occupation.

“There’s definitely a strong demand,” he tells me. Thatch is back in vogue and Mark’s order books are chocker for the coming year. More young people, he adds, are now turning to a once commonplace trade that, during the 20th Century, had dwindled to a diminishing band of hardy artisans.

I always look out for that smart, thatched abode whenever I’m motoring through Lower Wanborough following my encounter with Mark a few years ago.

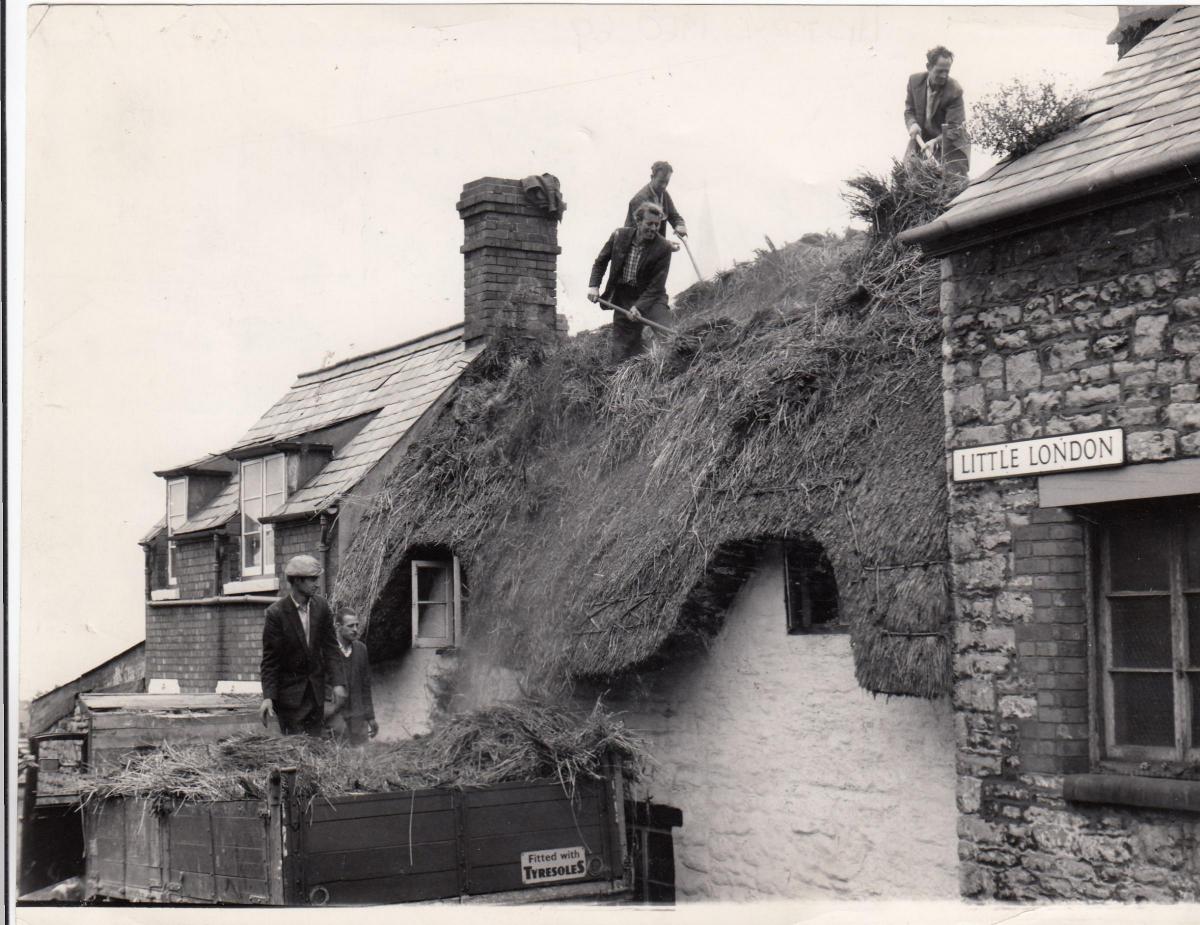

And it invariably conjures images of a structure that once stood in Swindon for nearly 300 years: Number 4, Little London, Old Town – “The Old Thatch,” at the back of the Adver offices.

Just over half a century ago this unassuming home on a sloping backstreet attained a history of sorts that signalled the end of an era in Swindon – one which had lasted for centuries, possibly as long as the ‘settlement on the hill’ had been inhabited.

It was Swindon’s very last thatched cottage and it finally bit the dust in 1964. Thatch was yesterday’s thing – a vermin infested, unreliable shelter from the storm and increasingly expensive to maintain.

But now, in the 21st Century, they’re building much sought after thatched homes that off-load for half-a-million quid or so.

The Old Thatch was built around 1700, when William of Orange was on the throne and Swindon’s population was around 800.

According to local historian Mark Child in The Swindon Book Companion, the cottage is understood to have been occupied by the same family, the Lawrences – glovers, by trade – for well over 200 years.

The last of the Lawrences was Alfred, a bell ringer at Christ Church for 77 years who died in 1945 aged 90, after which the property fell into the hands of his granddaughter, Ivy Liddiard.

Old Town was once heaving with such cottages. Growing up in the predominantly rural, hill-top community during the mid-1800s, Swindon Advertiser founder William Morris (1826-1891) noted that his father’s book shop was one of the few in town with a stone roof.

Over the decades, as the 19th Century became the 20th, thatched cottages slowly vanished, reduced to scattered reed and rubble as new homes, flats, petrol stations and car parks arose.

And then, as the Sixties dawned, there was only one left.

Revealing to the Adver in 1963 that Swindon’s last thatched cottage was about to be sold, Mrs Liddiard told us she had been brought-up in the low-ceilinged, oak-beamed home, surrounded by toby jugs and horse brasses.

She had lived there since 1918 but was moving to Tennyson Street to be nearer her husband’s place of work.

Today, such a property would fetch a very decent price and be earmarked for a Grand Designs type make-over.

But no, it was acquired for an undisclosed sum so it could be flattened to provide access for a loading bay for premises in Wood Street. “A bit of the country in the heart of Swindon will be pulled down,” we declared.

A year later “progress has at last caught up with this old thatched cottage – the last in Old Town,” the Adver reported as the demolition men and thatch extractors moved in.

It must have been a sad sight – or maybe I’m looking at it through nostalgia-tinted spectacles. By then thatched cottages had long since been associated with rural poverty and hard times.

As our photographs graphically illustrate, great tufts of reeds that had adorned the attractive black and white painted structure for many years were methodically forked and sheared away before the place was bulldozed.

Sifting through aged rubble workmen unearthed nothing more than an old farthing and a 1930 Bible. Life is full of disappointments.

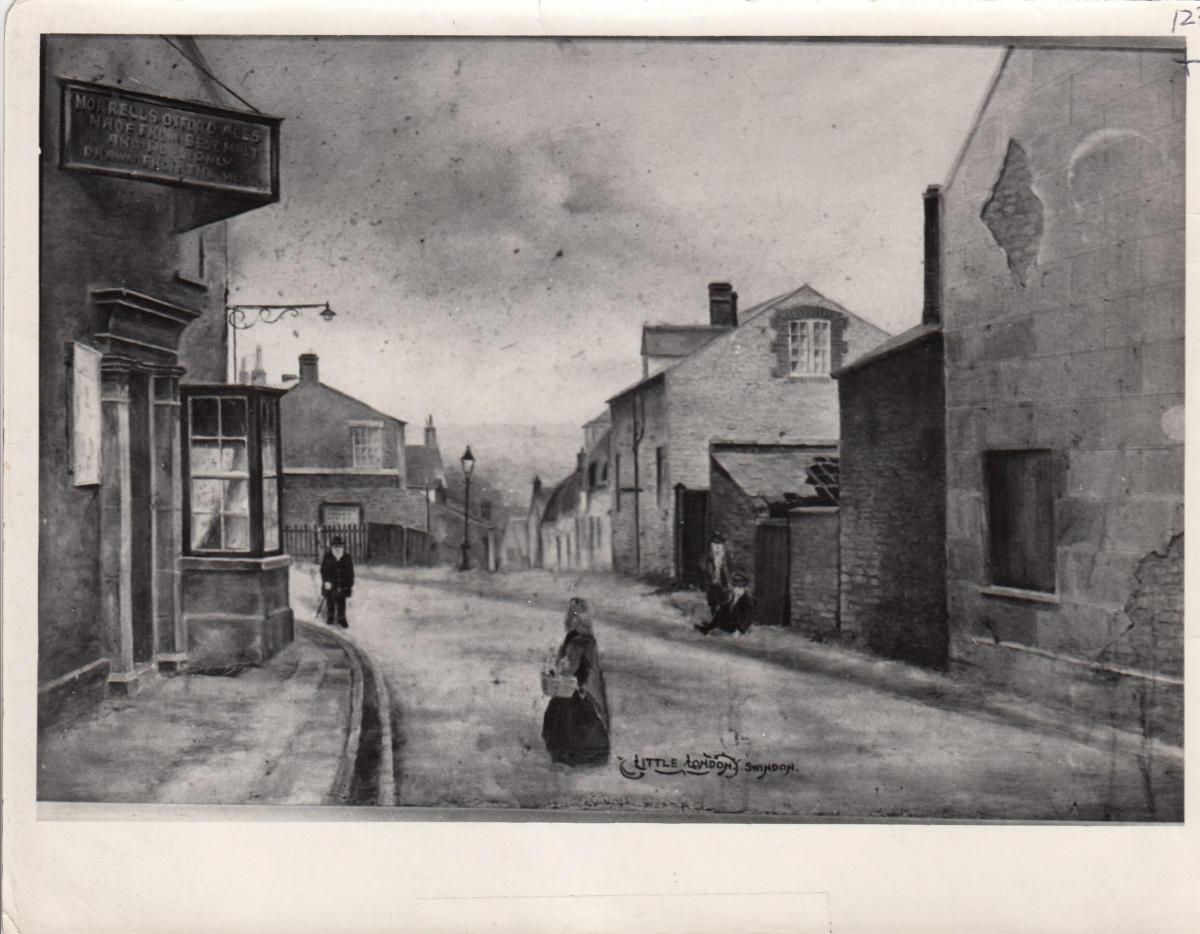

ANYONE who thought Swindon’s Cockney invasion began during the post war years when overspill families from London headed for a new life in the west were around 150 years off the mark.

At the dawn of the 19th century migrants from the capital erected their thatched homes on fields trailing downhill from Wood Street, one of the four roads bordering Old Town.

After becoming London Lane, Little London Lane and London Street its occupants eventually settled on Little London.

Perhaps they should have gone for Little East End, as a nod to some of London’s less salubrious corners.

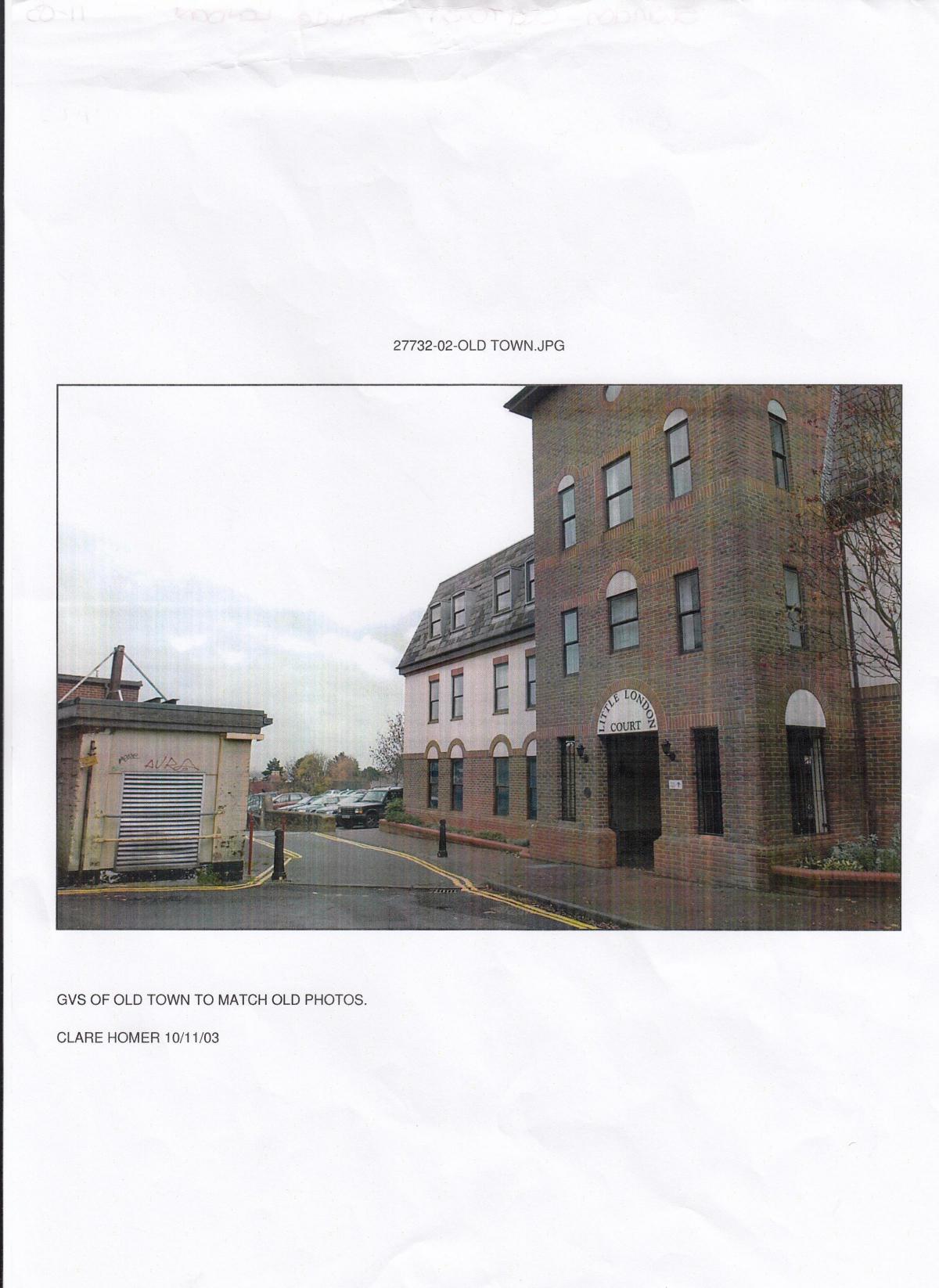

Today it is home to a modern, redbrick office complex - Little London Court – while a car park stands in an area once crammed with cottages of roughly hewn stone.

But back in the day it was the proverbial den of iniquity with brawls, cock-fights, assaults, hideous health conditions, prostitutes openly plying their trade and all manner of alcohol related skull-duggery.

You’d have to have been pretty rough around the neck, or in dire need of an after-hours shot of alcohol, to have sallied along the back street after dark.

Swindon historian Mark Child described the area as “the centre of low life and depravity.”

He wrote: “By the mid-1800s the southern end of Albert Street, Little London and Back Lane were effectively a single thoroughfare albeit one that only its inhabitants would want to traverse.”

CENTRAL to the Little London hot-bed of vice and villainy was The Rhinoceros beerhouse at the bottom of Albert Street – condemned by one Swindon magistrate as “the most notorious house in town.”

It was described in court as frequently the scene of bad behaviour where landlords flaunted licensing laws.

A large room at the back of the hostelry was used for “dancing, cock fighting, glove-fighting and almost every conceivable vice.”

Opened by former dress-maker Lucy Rogers in 1845 it was her son-in-law Joseph Patchett who was the driving force behind its infamy.

Running the establishment “in a most disreputable manner” he was regularly hauled before the beak for a variety of misdemeanours while in charge of the beerhouse.

In his Swindon pub book Home Brewed, Dave Backhouse tells us that Patchett’s first recorded court appearance was in 1847 when he was prosecuted for being open at 1am with 200 people jammed into the premises.

Other charges followed ranging from keeping an open sewer at the back of the premises to allowing a drunken and disorderly prostitute to ply her trade inside.

Another court case involved a woman who sustained a serious cut from a spittoon!

Patchett was eventually charged with killing Lucy by whacking her over the head but was acquitted and moved to the nearby Red Cow in Cow Lane (both gone).

Venturing back to his old Little London patch, he fell into a row at The Lord Raglan (also gone) in Cricklade Street which he settled by pouring the contents of a privy over his adversary’s head.

Things hadn’t improved much at The Rhinoceros, either, which was prosecuted in 1867 for selling putrid meat.

“All this went on,” wrote Dave “despite no less than three constables living in Albert Street.”

The corner pub was closed in 1869 on the grounds that “there was a prostitute living on the premises”.

The building became a lodging house for almost a century before it was bulldozed to make way for the Adver’s garage extension.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here