We’ll never forget the music, the laughter... and the man

THE daily routine of knocking out news stories for the broadsheet Swindon Evening Advertiser, with its three editions-a-day, is broken one morning in the summer of 1985 with a message from reception. “There’s someone here to see you, his name’s Paul.”

About 30 seconds later I can see Paul Griffiths sitting there with a big cheesy grin. Always great to see Paul. And on this occasion he has some hot news. “Guess what… I’m big in Italy.” He’s suddenly laughing his head off and I feel compelled to join in.

He has this special way of laughing, Paul – kind of manic and staring you right in the eyes.

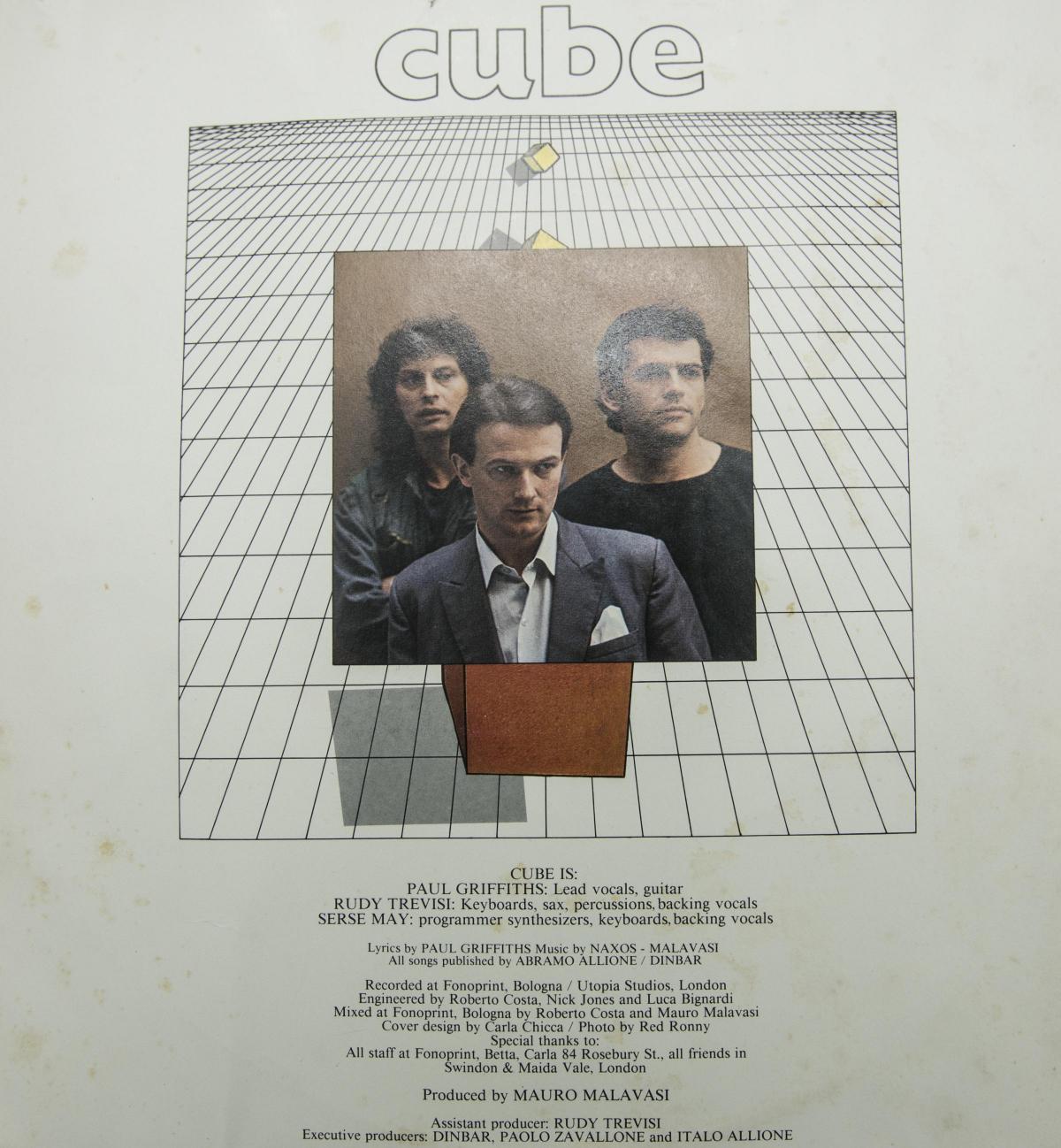

“Have this,” he smiles, thrusting an album into my hands. It’s by a band called Cube. On the inner sleeve there’s a photo of three musos. Looking smoother and slicker than I’ve seen him before – and he is always a pretty sharp dresser – Paul is flanked by keyboard players Rudy Trevisi and Serse May.

He has become the voice, wordsmith and frontman of an “Italo Disco” synth-pop trio with a Human League-like electronica vibe. They’ve had some hits, too: a couple of Top Five singles and another that made the Top 20, all from the aforementioned LP Can Can In The Garden.

They’ve been on the telly and everything, he’s telling me. And how about this – Paul Griffiths gets chased down the road by Italian teenyboppers. What a hoot. He can barely contain his amusement.

“Speak some Italian then,” I request. And he does, in a Swindon sort of way. Paul proceeds to enthuse about pasta, Bologna - where the band is based - and wine. All this is a bolt from the blue. Last time I saw Paul he was with a Swindon band called The Tears.

What happened to them then? “Oh, we’re still together,” says Paul, who is off to Italy again in a couple of weeks to promote Cube’s fourth single, Performance. “The Tears are close to my heart,” he says. “We’re on at The George next week – come along.” Two bands, we both agree, are better than one.

Just over 30 years later, on the wintry night of Monday, November 23, 2015 il Tricolore flutters over The Old Lady on The Hill – a poignant salute to Paul’s Italian sojourn following his funeral at Christ Church a few hours earlier.

Paul Griffiths was raised in a musical household, his dad being a jazz musician who encouraged his children to sing, play and make merry with music. It was something Paul did with joy, talent and an infectious enthusiasm his entire life.

I first met Paul one memorable night in November, 1978, at an Old Town bar/bistro called The Bradford where he and fellow members of the group Stadium Dogs were holding court for the purpose of an article I was about to write about them.

They’d recorded an LP What’s Next? for Magnet Records, had acquired a snappy logo, and were about to embark on a nationwide tour. Virgin Records had previously been poised to sign them… but only on condition that they shave off their facial hair, deeming it not conducive to selling vinyl in the post-punk era.

Having nurtured impressive handle-bar moustaches Pete Cousins and Kirk Thorn impolitely declined while drummer Stan Pearce, who resembled a Grateful Dead roadie, was horrified.

Clean-shaven Paul, Jonathan Perkins and Kevin Wilkinson, who had recently replaced Stan, laughed it off and Richard Branson’s label was told to stick it. The Dogs toured Britain, Europe, supported The Kinks and briefly enjoying the more glamorous aspects of the rock’n’roll life backing Sweden’s second biggest pop star, Magnus Uggla, performing a string of sold-out gigs and being ferried around in limos etc.

The Dogs eventually went their separate ways and a couple of years later I’m at the Eastcott Hotel (The Tap and Barrel now) where Paul is at the bar drenched in sweat after his and Kev’s new band, 96 Tears (later The Tears) had performed a rollicking set of crisp, hooky pop songs.

It is obvious that Paul Griffiths is a songwriter/singer/guitarist of some measure – a fact that is conveyed to Italy where he is invited to front electro-dance outfit Cube. Performing on Italian Top of the Pops, they score hits including Two Heads Are Better Than One, Prince of the Moment and Concert Boy. Incidentally, about quarter of a century later, Paul returned to Bologna on holiday and was sheepishly wondering whether to pop into his once local patisserie. “They’ll never remember me,” he shrugged. “Oh, just go in” he is instructed. Seconds later “PAUL...”

All this time, as the bands, the gigs and the years fly by, we’ve been mates.

To quote an old Byrds song, He Was A Friend Of Mine. For more than a decade we slogged and wheezed around in the mud at the Polo Ground during our Thursday Night Old Codgers Football sessions (nippy down the wing, Paul). He gave me a black eye once. Me in goal, hurling myself at his approaching feet, and taking a knee in the face. A couple of days later I’m walking up Victoria Road sporting an absolute corker. Paul drives past and I swear his car is actually shaking with laughter.

Another great memory: waltzing arm-in-arm across The Beehive with Paul Griffiths after arriving home from Wembley, ecstatic after Swindon’s 4-3 win over Leicester.

And another one: watching cup finals every May at a friend’s house, drunkenly bemoaning perceived injustices meted out to the likes of West Ham (against Liverpool) and Portsmouth (against Chelsea).

Paul always brought along outrageously extra-strength lager on Cup Final Days and contrived to walk home upright (I’ve only just discovered how he did this).

Every now and then he’d give me a CD of his new stuff. What’s this? Sacred Ground by King Strut. Played it quite a bit at the time. The title track, a stirring, almost spiritual piece of music, left us all in tears when it was played at Paul’s funeral at Christ Church last week, following his death in September as a result of an illness.

Afterwards, at The Kings Arms, where Stadium Dogs had played back in the day, some of Paul’s contemporaries – Pete Cousins, Bob Bowles, Steve Degutis – performed in his honour. And then some young dudes stepped forward.

Paul had filled his house with music; visitors were encouraged, some would say gently press-ganged into picking up one of the many instruments lying around and giving it a go, making up a song, bashing a tambourine, strumming a banjo. Those now onstage were a new generation of Swindon musicians that were part of Paul Griffiths’ extended family including Finn Wilkinson, son of Kevin, his great pal and musical collaborator who sadly died in 1999.

With no little emotion, respect and talent they played an entire set of Paul’s songs. Leading from the front, Natasha – one of Paul’s three daughters – sang her heart out for her dad.

What a legacy…

Longtime friend and musician Barry Andrews remembers his artist buddy

Passion is a word which, much like awesome, is losing its power through misuse (‘the candidate will be passionate about database solutions’), which is a shame because it’s a very good word to apply to the Griffbag’s MO.

I have a school magazine from 1967 (Park North Juniors – Paul and I are both alumni of that distinguished academy) in which the 10-year-old Paul expresses, with simple eloquence, his view that Music is easily the best lesson; that the syllabus could be greatly enhanced if all the other lessons were Music as well, and that the music being taught in this now homogenous curriculum could – nay, must – include substantially more popular music, such as the oeuvre of the well-known Beatles.

The clarity and intensity of this proposition might have seemed mere childish enthusiasm but, with hindsight, we know better.

I can imagine the adult Paul still not seeing much wrong with this radically Muso-centric approach to educational policy.’

We had two main modes of interaction since I returned to Swindon in 2004 and saw a bit more of him:

1- caning bottles of wine and listening to each other’s tunes.

2- going to pubs during international games of – howyousay – ‘football’; Paul patiently explaining the nuances of the game to a soccer moron – so that I might drunkenly shout at the telly with at least the semblance of having an informed opinion.

In the first mode, our personal differences in this area, which we had both made our life’s work, were glaringly apparent: my songs full of unaccountable noises and bizarre lyrical wordscapes, barely sung; his with traditional plug-in-and-play instrumentation, universal themes of love and loss delivered in his wonderful note-perfect voice. One of our mutual friends once mused: was I the Anti-Paul?

Often, when the evening was becoming florid and all things seemed possible, we would discuss a collaboration but it was the wine talking: we both knew that such a project would be unnatural and an abomination before the Lord.

Paul was an artist, a man who ached to communicate, who spent his time learning to make beautiful things for people and worked hard at getting them right. A more honourable epitaph I cannot conceive.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here