DEVISED to celebrate the historic union of the Old Town on the Hill and the New Town below, Swindon’s motto – revealed in 1901, a year after the twain were finally spliced – was simple, unpretentious and to the point...‘ Salubritas et industria’ – ‘Health and industry.’

Some of the more cynical among us, however, may subscribe to the idea of a modern-day alternative...‘ Nescioquid lets pulso eam’ – ‘I Know, Let’s Knock It Down.’ Never a Bath, Bristol, an Oxford or a Cheltenham, we have not been blessed with a surfeit of historic, architecturally outstanding structures. To use John Betjeman’s oft-quoted observation from Studies in the History of Swindon (1950): “There is very little architecture in Swindon but a great deal of building.”

However, some of the fabrications that were consciously designed to please the eye or artfully avoid the norm that we actually did possess have fallen victim to the ball and chain only to be replaced with... well, you can make-up your own mind, the evidence is there for all to see.

Now plans are afoot to demolish the Big Top, our tented market. “What’s the problem,” you may remark. “It’s only been there a smidgeon over 20 years.” That’s right, but during its existence our five-peaked canopy market has become a distinctive element of, let’s be honest, a fairly ordinary town centre.

It has character, it catches the eyes, it is different. If you didn’t know Swindon you’d think the circus was in town, or that there were some dodgems noisily bumping into each other beneath its ski-slope, helter skelter canvas roof.

Importantly, it also continues a market tradition dating to the 13th Century when our old settlement was known as Chepyng (meaning ‘market’) Swindon, and later Market Swindon.

Do the developers behind moves to flatten our fairground-like attraction give a fig about tradition – or that the market provides a welcome, you could say vital alternative to the wares dispensed at the generic High Street chains that dominate the town centre? We all know the answer.

They want to build some restaurants which of course, we desperately require – especially after half-a-dozen of them recently opened a few hundred yards down Commercial Road at the old college site.

As market traders angrily fight for the right to earn a living while their tented home faces the chop, it is worth examining some of the other interesting, attractive and endearing Swindon buildings that have been reduced to rubble in the name of progress...

Erected in 1875 at the behest of ambitious Irish draper William McIlroy, for 123 years it dominated the heart of Swindon. McIlroys – “The House For Everything” – was a Swindon institution, second only to the Railway Works and possibly Arkells Brewery. With its distinctive clock tower, added in 1904, this imposing department store became one of our most familiar landmarks as it gazed upon horse-drawn carriages, trams, all manner of motorised conveyances and then simply hordes of pedestrians.

When our very own Grace Brothers surprisingly and sadly announced its imminent closure in 1998 how many of us, perhaps naively, thought the building, with its delightfully sweeping staircase, would at least survive?

Like key structures at the Swindon Railway Works, surely other uses could be found for such a prominent town centre feature – perhaps that it could be compartmentalised into traditionally styled independent units.

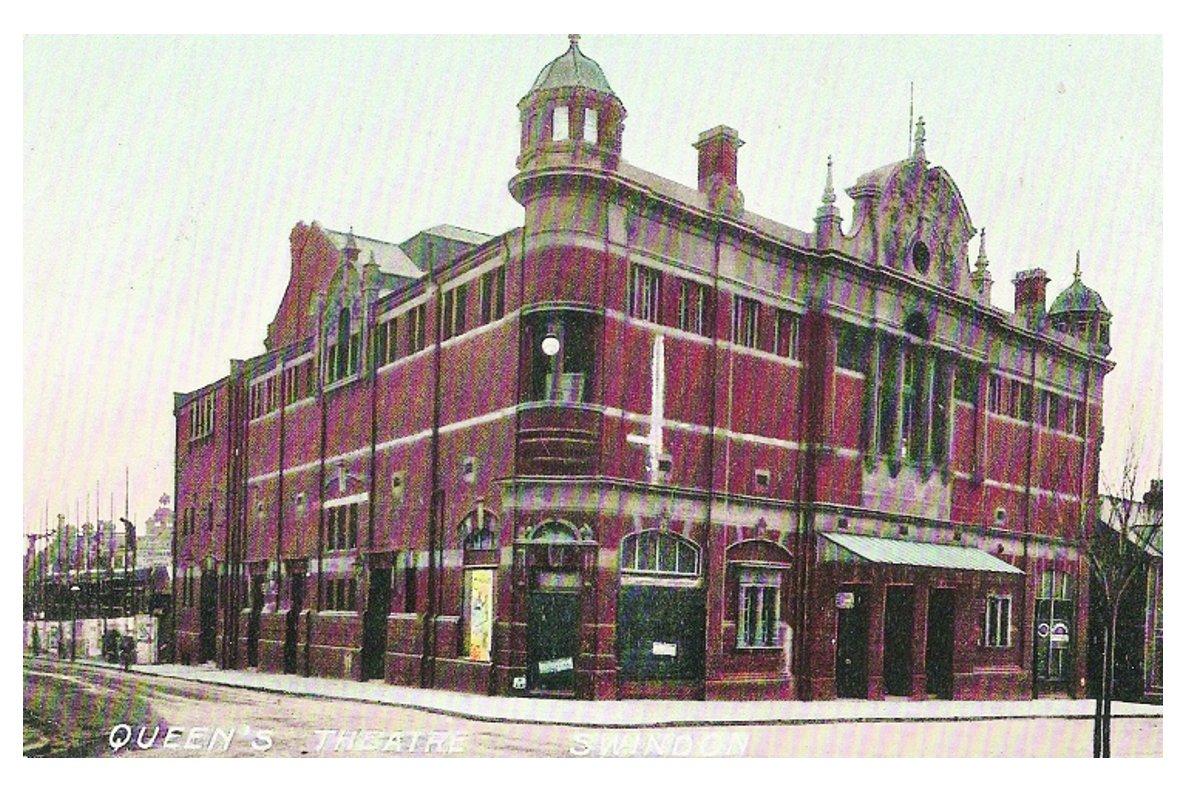

Nah, they pulverised it before putting up something, well, mediocre (but at least it has a clock tower.) As towering edifices go, they didn’t come any more impressively towering – for Swindon anyway – than the Empire Theatre, with its “free Rennaisance style” façade, fancy turrets, stone columns and ornate auditorium.

Built in 1897/98 at the foot of Victoria Road where it meets Groundwell Road, the aim was to achieve an “architecturally inspirational property commensurate with the aspirations for the developing Swindon.”

That they did, but when the End of the Empire arrived in 1959, the wrecking crew moved in to tear down the house.

Arising in 1960 from a sorrowful cloud of redbrick Swindon dust was an office block called Empire House that is so bland and faceless that, it is rumoured, even those who work there have no idea what it looks like.

Described in 1847 as “the only mansion in the neighbourhood” and of the “Elizabethan order of architecture,” stately Kingsdown House, with its oak staircase and fine embellishments was – to quote this newspaper in the early 1950s – a “mellowing mansion whose quaintly designed chimneys have weathered a century and more…”

Somewhat ignominiously, it was razed to make way for Kingsdown Crematorium in 1955.

Outrage still lingers over the fate of the Baptist Tabernacle nearly 40 years after it was dismantled amidst waves of anger and controversy.

Acclaimed architectural guru Nikolaus Pevsner lauded it “remarkably purely classical” while Poet Laureate Betjeman loftily compared its architecture to London’s St Martins in the Fields.

But demolished it was and today 260 tons of its once grand colonnaded facade lay under wraps at Wroughton airfield hoping for a return to the town centre, the council having purchased it for £360,000 in 2007.

When Lower Stratton realised that its children needed a school during the 1860s local menfolk quite literally put their backs into it.

Voluntary workers in 1869 created something not just fundamental to a modern society but – with its traditional bell tower and ecclesiastical school hall – a structure of immense charm and elegance.

Just over a century later the National School in Swindon Road was flattened to be replaced with two houses. “Another landmark falls to the demolition experts,” rued the Advertiser in 1974.

You can’t help feeling that today it would have been saved and converted, a la Grand Designs.

Sadly, we can’t confine the bulldozing of Victorian schools to a long gone era. Barely two years ago, conservationists understandably saw red when another of our 19th redbrick structures, Even Swindon School in Rodbourne, received a one-way ticket to oblivion.

“Derelict, dangerous and fire damaged – it has to go,” proclaimed the council.

But as the Swindon Civic Voice declared: “It is part of the town’s heritage... part of the character of Rodbourne… the council are launching a new heritage strategy but they are tearing this building down.” Which, of course, they did.

Perhaps some of the vanished structures mentioned in this article were beyond salvation – or at least, had been wilfully allowed to go beyond salvation.

With a bit of vision, a bit of planning and a nod towards our history and built heritage, some – without question – should still be standing.

So when Swindon’s esteemed planning committee debate the fate of the Tented Market, with historic links harking back 800 years, don’t be surprised if the conclusion is: “I know, let’s knock it down.”

- WITH elements of Gothic and neo-Tudor architecture, The Hermitage – as we were keen to point out more than 20 years ago – was “one of Swindon’s best loved buildings.”

When that phrase appears in the Adver you can usually assume that the demolition boys are about to don their hard hats and rev-up the bulldozers.

Erected just off Market Square around 1830 – a stone’s throw from the stately but long gone Lawn mansion – The Hermitage was a private house that was acquired in 1964 by the council.

They ran it as a nursing home before it was pulled down 30 years later after falling into disrepair.

Naturally, there was a hoo ha which at one stage saw Environment Secretary Michael Howard side with campaigners attempting to prevent its destruction.

Gwenda Barnes of the Pipers Area Residents Association said they were “very much against the Hermitage being destroyed… so much of Old Town has been destroyed this century, especially during the last 20 years.”

They were, she added, “trying to preserve what little we have left.”

But flattened it was, to make way for a private elderly people’s complex.

Perhaps the “elegant but crumbling landmark” should not, however, have been allowed to slide into such a ruinous state in the first place by its civic owners who faced a barrage of criticism over its “philistine attitudes.”- For almost 40 years from the 1850s an octagonal market, built for the people of New Town, adjoined the today almost four decades’ derelict Mechanics Institution that was replaced with a fine, triangular redbrick Market Hall in Market Street in 1892.

Down it went in 1977 in favour of a grim, soulless hall that was swept aside – no tears here – by the House of Fraser.

Our quirky Big Top – now in danger of being toppled – went up amidst a great fanfare in 1994.

- For almost 40 years from the 1850s an octagonal market, built for the people of New Town, adjoined the today almost four decades’ derelict Mechanics Institution that was replaced with a fine, triangular redbrick Market Hall in Market Street in 1892.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel