NINE hundred and thirty years ago something quietly momentous occurred in Swindon, something that would echo through the centuries although it probably didn’t seem such a big deal back then. The name of our town was written down and recorded for what was almost certainly the first time.

It is interesting to imagine the conversation between William the Conqueror’s scribes as they traipsed regally around the kingdom compiling The Great Survey of 1086, and the good folk of this modest AngloSaxon settlement that is perched on a limestone mound.

“So, what exactly do you call this place then… this hill?” Err, we call it after them porkers snorting over yonder. So, it is swinedown then – pig hill – Suindune. At least, that’s the popular consensus, be it a reference to domestic pigs or perhaps hordes of grunting wild boar.

A less subscribed theory is that our moniker derives from Sweyn Forkbeard, Danish King of England and brutish father Canute who took a liking to our hillock and claimed it for his own while on his way to brawl with some Saxons in Bath in 1013...thus Sweyn’s Hill – Sweyn-Dun.

I prefer the pigs: there’s something gritty and down-to-earth about it... much like Swindon today.

Before the Conquest, Swindon Hill – the future Old Town – had been known as ‘Thanesland,’ which sounds suspiciously like Thamesdown. Who was Thane? Some long forgotten Saxon, maybe.

Twenty years after The Battle of Hastings, however, the word Suindune was officially agreed upon and inscribed half-adozen times in that doorstep of a Medieval Latin manuscript, The Doomsday Book.

Lords of the six estates of post-Conquest Suindune included William the Conqueror’s half-brother Odo Bishop of Bayeux – a thug in liturgical vestments who, paradoxically, is said to have commissioned that enduring snapshot of Hastings, the Bayeux Tapestry.

Other nouveau riche Suindunians included Miles Crispin who was also the Lord of Wootton, a knight called Wadard (who like Odo has been immortalised in action on the Bayeux Tapestry) and a certain Odin The Chamberlain. All had acquired their slice of Suindune as booty for helping vanquish Harold in 1066.

“So far as is known The Doomsday Book has the oldest record of Swindon’s name,”

wrote historian HS Tallamy in the 1950 publication, Studies In The History of Swindon.

Frustrated at not being able to reveal more concerning Swindon’s misty past, he complained: “History has yielded grudgingly sources for the history of the town.”

Medieval records, he stated, were so few that “the majority of its ancient townsmen and townswomen must be left to sleep amongst the ranks of the great army of the anonymous.”

It would be another three centuries, Tallamy pointed out, before “the humble Swindon peasants get their names into the records.”

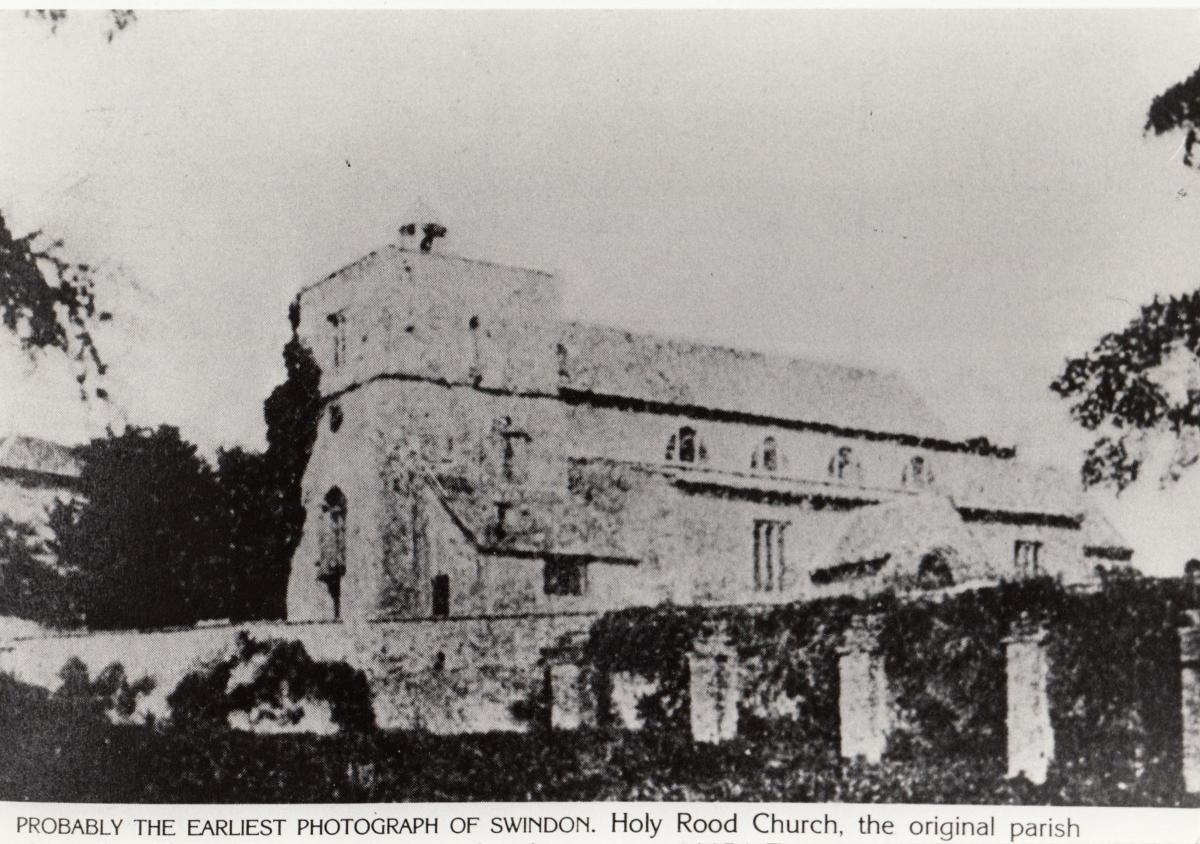

The only remnants from Swindon’s early medieval era when our Norman overlords ran the show are located amidst the atmospheric, verging-on-spooky-at-dusk ruins of Holy Rood.

Located in Lawn parkland and now padlocked against modern-day invaders (vandals, graffiti scrawlers, individuals seeking a secluded refuge to get high), Holy Rood, it can be argued, is The Very Heart of Swindon.

It is felt there may have been a wooden Saxon church on the spot where the more permanent Holy Rood (rood meaning cross) later took root centuries before the arrival of the Normans.

There is some dispute over whether any remnants of a stone church from the late 11th Century still exists. If it does it was almost certainly built upon during later construction.

At a lively meeting of the Swindon Local History Study Group at the Central Library in March, 1963, Norwegian-born PR Broderstad, a retired grocer of Prospect Place, asserted that it was Odin who began work on Holy Rood.

Of Norse descent himself, Mr Broderstad, a Swindon resident since 1914, claimed that Odin, who owned around 1,500 acres here, built the church to “make amends for his Viking sins.”

But he never completed the job because “he probably died” after being recalled by William to help quell a Saxon rebellion.

Swindon photographer/historian Dennis Bird said in his booklet The Story of Holy Rood that no-one knows – or indeed, was ever likely to – when the original church was built.

It may, he felt, have been erected by the Pont de l’Arche family – the Normans who became lords of the manor after swallowingup Odin’s turf.

The earliest reference to Holy Rood is from 1154 shortly before the Pont de l’Arches gifted it to Southwick Priory in Hampshire.

The oldest accepted part of the church dates to 1280 when the priory re-fashioned it, which makes Holy Rood Swindon’s oldest structure by a country mile (although neighbouring St Michael’s in Highworth and St Mary’s at Lydiard are also 13th Century.) A 730 year-old arch in the chancel (the area near the alter) features badly eroded stone heads of a king and queen – possibly Edward I and Eleanor of Castille.

Holy Rood was revamped several times over the centuries, acquiring some fine architectural additions and embellishments courtesy of the Vilett family, who snapped it up in the 16th Century, and later the Goddards, our lords and masters until the early 20th Century.

It was doomed, however, by Swindon’s growth, having become “woefully small”

and in 1851 made way for the spanking new Christ Church which itself is now considered The Old Lady On The Hill.

Even its bells were ignominiously carted off to chime from the lofty tower of Christ Church – the highest point in Swindon.

Holy Rood’s demise was a slow, arduous affair interspersed with occasional attempts to at least stop the rot, including some crucial restoration (see panel.) The tower and nave (its main body) were demolished more than 160 years ago. The chancel which represents about 15 per cent of the old structure today stands as a unique reminder of Swindon’s medieval past but has become an exclusive playground for squirrels after being locked inside Holy Rood’s craggy, ivy-clad outer walls.

The remnants of the nave arcade, meanwhile, cut a striking, skeletal figure that approach the realms of romantic ruin come the JOHN Alexander may not be a familiar name to most of us but the inscription on his tombstone at Holy Rood suggests he was a remarkable man… because he lived until he was 117.

John was born in 1580 and passed away in 1697. His wife Ann died young – she only made 98.

The hardy old fella was around for the reign of six monarchs – from Elizabeth I to William III – plus Oliver Cromwell sandwiched in between.

That, of course, is if the inscription is to be believed… Many memorial tablets that have been re-positioned at Holy Rood over the years, are today indecipherable through age and corrosion.

Others have been restored, such as a 200 year-old stone bearing the partially eroded inscription “Eliz.”

Swindon’s master stonemason Ron Packer, who revived the tablet in 1977, said the 18th Century memorial was “so well done, so graceful and wellproportioned that it wouldn’t disgrace Westminster Abbey.”

leightonbarry@ymail.com Barry Leighton HE WRITES WHAT HE WANTS ... EVERY WEDNESDAY “IT is absolutely pathetic. A blind tramp could get in there.”

Captain John Goddard, a member of the family that once held sway in Swindon, was having a right old pop at our council.

His gripe? That vandals had once more desecrated the Goddard Family Vault at Holy Rood, having gained access “far too easily.”

On this occasion, in 1990, they had smashed up the stone slabs on top of a sarcophagus – no easy feat – where the remains of various Goddards had been entombed for centuries.

“The coffins are completely exposed. There is a whole load of broken bones and human remains inside,” complained Captain Goddard, of Cirencester, with understandable ire.

Despite the upping of security it was, alas, a familiar tale over the years.

Our own medieval monument ONE hundred years after Holy Rood ceased to exist as Old Swindon’s parish church it had become an unrecognisable eyesore.

The chancel was littered with broken monuments and crumbling masonry, as pictured in the Swindon Advertiser on November 25, 1954.

“I cannot put out of my mind the appalling present state of the churchyard,” complained the Chancellor of the Bristol Diocese.

Things didn’t improve when Swindon Corporation started work on its restoration.

“The font in which many Swindonians of past generations were baptised is being used by workmen as a block for sawing wood,” we grumbled with due outrage.

It is a picture, added the Adver sadly, of neglect and desolation.

But it all came good eventually when in May, 1971 hundreds of people stood in the rain to celebrate the project’s completion in an outdoor ceremony filled with moments of “quiet drama,” as we described it.

right atmospheric conditions.

Cracked and weather-beaten tombstones also abound, some lying in pieces on the grass, others artistically re-positioned along the walls while the Goddard family vault that has been sporadically trashed by the intelligentsia over the years, is pure Hammer Horror.

Increasingly infrequent services have been staged at Swindon’s first church which, as author/historian Brian Bridgeman pointed out, were always “a moving experience at a spot hallowed by centuries, if not millennia, of worship.”

Holy Rood’s significance in Swindon’s history and heritage, then, cannot be underestimated.

Dennis Bird wrote: “To say that ten thousand people may have been buried here may be no exaggeration.

“For although the population of early Swindon may have numbered no more than a few hundred souls at any one time, it was here that nearly all found their last resting place, generation after generation, for perhaps more than 700 years.”

- JOHN Alexander may not be a familiar name to most of us but the inscription on his tombstone at Holy Rood suggests he was a remarkable man… because he lived until he was 117. John was born in 1580 and passed away in 1697. His wife Ann died young – she only made 98. The hardy old fella was around for the reign of six monarchs – from Elizabeth I to William III – plus Oliver Cromwell sandwiched in between. That, of course, is if the inscription is to be believed… Many memorial tablets that have been re-positioned at Holy Rood over the years, are today indecipherable through age and corrosion. Others have been restored, such as a 200 year-old stone bearing the partially eroded inscription “Eliz.” Swindon’s master stonemason Ron Packer, who revived the tablet in 1977, said the 18th Century memorial was “so well done, so graceful and wellproportioned that it wouldn’t disgrace Westminster Abbey.”

- “IT is absolutely pathetic. A blind tramp could get in there.” Captain John Goddard, a member of the family that once held sway in Swindon, was having a right old pop at our council. His gripe? That vandals had once more desecrated the Goddard Family Vault at Holy Rood, having gained access “far too easily.” On this occasion, in 1990, they had smashed up the stone slabs on top of a sarcophagus – no easy feat – where the remains of various Goddards had been entombed for centuries. “The coffins are completely exposed. There is a whole load of broken bones and human remains inside,” complained Captain Goddard, of Cirencester, with understandable ire. Despite the upping of security it was, alas, a familiar tale over the years.

- ONE hundred years after Holy Rood ceased to exist as Old Swindon’s parish church it had become an unrecognisable eyesore. The chancel was littered with broken monuments and crumbling masonry, as pictured in the Swindon Advertiser on November 25, 1954. “I cannot put out of my mind the appalling present state of the churchyard,” complained the Chancellor of the Bristol Diocese. Things didn’t improve when Swindon Corporation started work on its restoration. “The font in which many Swindonians of past generations were baptised is being used by workmen as a block for sawing wood,” we grumbled with due outrage. It is a picture, added the Adver sadly, of neglect and desolation. But it all came good eventually when in May, 1971 hundreds of people stood in the rain to celebrate the project’s completion in an outdoor ceremony filled with moments of “quiet drama,” as we described it

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel