“I’LL take you on a little walk,” says Steve Rosier, writes BARRY LEIGHTON. Seconds later we are behind the mesh security fence and brushing our way through a tangle of weeds, bushes, nettles and trees while tramping over fragments of masonry and assorted rubbish. It is like entering some tumbledown, long-abandoned mansion that is being eagerly reclaimed by nature.

Myself and Adver photographer Tom Kelsey are decked in fluorescent safety jackets and hard-hats but Steve’s been here so many times he doesn’t bother anymore.

“Nothing’s going to fall on us,” he shrugs, surveying the chaos. “I’m bored with coming in here and seeing it in this state…”

But he soon perks up.

“That’s my favourite part of the building. Once it had a glass dome ceiling held up by cast iron columns and also an artistic fountain,” he says.

How wonderful it would have been, we muse, to have seen it in its heyday more than a century-and-a-half ago.

Steve is referring to the Butter Market, an oddly triangular-shaped structure of which only the walls remain. But what fine arcaded stone walls they are, if a tad unloved.

In his head Steve can see these arches stylishly illuminated as part of a dramatic renovation that he has been planning for a decade.

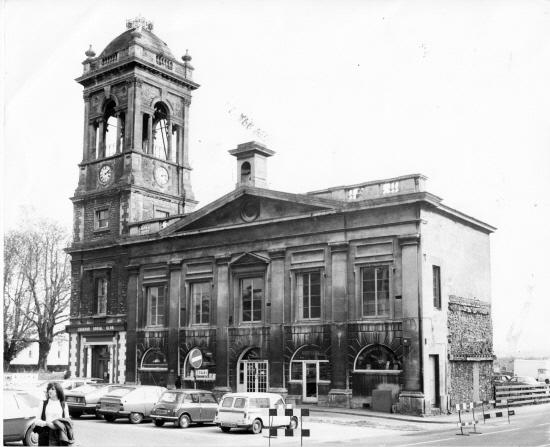

The Butter Market forms the smallest section of the Town Hall/Corn Exchange complex that sits in the heart of Old Town, adjoining Swindon’s 750-year-old Market Square that is now a grubby car park.

Pretty much everyone in Swindon knows this formidable, once elegant building that is boarded-up, fire-ravaged, partially collapsed and weed choked.

It has been derelict for 32 years, has twice been catastrophically assailed by arsonists and is unquestionably one of Swindon’s most important heritage buildings.

Steve is the project manager behind a £35million plan to restore it.

Our 25-minute recce on a sunny August morning provides a graphic illustration of what happens when a structure is locked up and left to the elements, the vandals, the graffiti-kids and the fire-starters for more than three decades.

We press on and find ourselves at the base of the 80ft Italianate clock tower, craning our necks to see a square of sky shining from above.

The top of Swindon’s citadel is crowned with an ornate clock chamber complete with Venetian windows and Corinthian pilasters.

Its domed roof and floor, however, have long since collapsed and bunches of weeds sprout from the pinnacle, as if to emphasise its abandonment.

“It’s the highest view in Swindon,” enthuses Steve.

“We are planning a viewing platform so the public can walk up and enjoy looking out.”

Steve has never been up the tower – the last to do that were the contractors who made it safe following a second fire 12 years ago.

But the views are “unbelievable,” he asserts, having seen Swindon and its surrounding countryside from the top floor of the adjoining, though much lower, HSBC Bank.

“We plan to install four new clocks in the tower,” he says. The original, which once chimed every 15 minutes, was made in 1866 by Swindon jewellers Deacons – as will be the new quartet of public timepieces.

Now Steve is leading us up some metal steps.

“This is the Corn Exchange Hall… mind the hole.”

We peer over a jumble of rampant wild flowers and nettles and try to imagine the scenes in this roofless space when it thrived during the post-World War Two years as the Locarno Dance Hall – first hosting jazz and jive action before Sixties pop upstarts such as The Who, The Small Faces and The Yardbirds ripped the joint.

The fine Canadian maple wood dance floor that once graced The Locarno is “right down there,” points Steve, it having collapsed into the basement along with its lofty roof.

We progress up more railings to a graffiti afflicted corner converted almost a century ago into the projection room for The Rink Cinema, which in 1919 replaced the earlier roller skating rink at the Corn Exchange.

Films were projected through square holes in the wall, delivering movie magic to wide-eyed Swindonians in an era that saw silent flicks evolve into the talkies.

The racks where reels of film were once stored are still there.

It later served as a cloakroom for The Locarno and a heap of wooden coat hangers litter the floor amongst other junk and debris.

Discarded red and white bingo tickets bear witness to the building’s final incarnation as a bingo and social club until 1984.

We descend into the earliest part of complex, the 1850s-built Old Town Hall.

I was last here about 35 years ago, acquiring a bottle of plonk when it served as an off-licence.

Today there is virtually nothing to see except a rude intrusion of bushes and trees amidst fire-scorched timber that crashed into an already derelict building during the first fire.

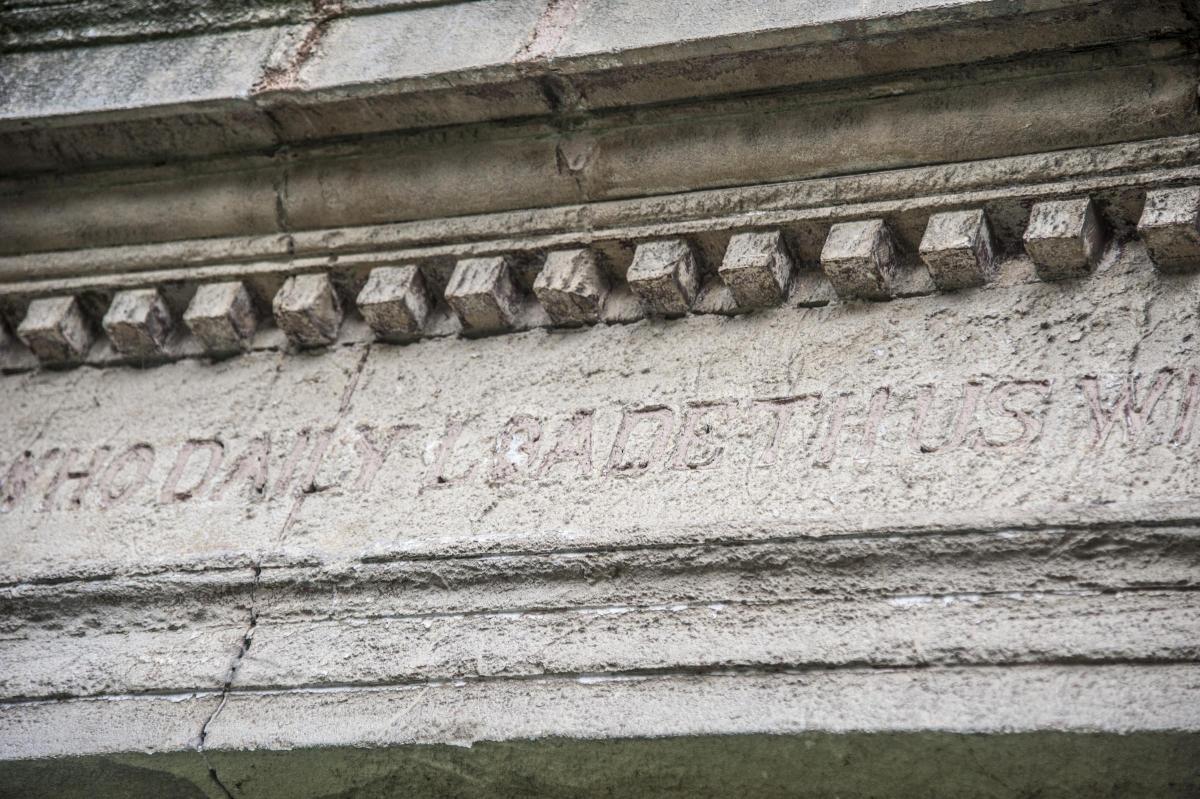

As we make our way back through the foot of the clock tower we can make out the 1867 inscription above the original entrance: “Blessed be the Lord who daily loadeth us with benefits.”

The craftsmanship applied by Victorian builders and architects to Old Town’s most distinctive structure is obvious, in particular the admirable but now tree-encroached Ionic – or should that be ironic – columns.

It is a view that reminds me of some ancient, once dignified structure that has been re-discovered after decades in the wilderness… only this happens to be in the middle of 21st Century urban Swindon.

- IT is difficult not to walk past the boarded-up shell of The Exchange without experiencing a range of emotions: sadness, anger and embarrassment that such a scenario should have been allowed to occur, writes BARRY LEIGHTON.

Swindon was never blessed with a surfeit of grand old buildings but some of the more worthy examples are, for various reasons, now history.The Baptist Tabernacle, The Empire Theatre, The Old Market, The Hermitage, Lawn mansion and McIlroys department store only exist now as images in local history books and on nostalgia websites.

And look at the Mechanics Institution – a Grade II* building central to the emergence of New Swindon and thus of the town we know today, whose future continues to remain uncertain well over 30 years after its doors were closed.

There have been successes where tasteful redevelopment or refurbishment of our Victorian heritage has been achieved: the Railway Village, a large chunk of the Railway Works and Old Town’s former Belmont Brewery (converted into The Mission nightclub), that is now a restaurant.

In my view it would be a crime of sorts if today’s £35million “mini Covent Garden” project which has been hit by a string of set-backs over the last ten years was not wholehearted backed and allowed to proceed.

OK, the tricky issue of public parking needs to be addressed and options are being examined.

However this is nothing less than Old Town’s most important regeneration scheme and if it doesn’t happen then that will probably be that for this crucial slice of Swindon heritage.

- FOR more than three decades umpteen redevelopment schemes have been earmarked for the building that is now officially known as The Exchange.

But for various reasons – until now – they have all collapsed.

There was a more literal collapse in 2003 when most of the structure was reduced to a shell as a result of a devastating arson attack.

The clock tower escaped largely unscathed but this too was seriously damaged when fire-starters struck again a year later.

However, the stone walls are of such sturdy nature that they have weathered years of dereliction and fire damage without wilting and will now form the basis for The Exchange’s dramatic and long overdue comeback.

- SWINDON’S neo-classical Old Town Hall arose next to the Market Square between 1852 and 1854. The ground level served as a market hall and for storage.

The upper floor was used as civic offices and a court room while an adjoining wine store was later added.

Swindon’s rapid growth and prosperity required a larger Corn Exchange which was completed in 1866 in “Grecian architecture” and boasted an 80ft, four-stage clock tower and an ornate triangular Butter Market.

But a disastrous drop in corn prices due to cheap imports resulted in the Corn Exchange’s large hall being converted in 1888 into a 1,000 seat auditorium for theatre, banquets and bazaars.

The cellars were deployed by wine merchants Brown and Nephew. During the early 20th century the theatre was transformed into The Rink roller skating rink before it was supplanted in 1919 by The Rink Cinema.

The post-World War Two years saw it reemerge as The Locarno Dance Hall where the likes of the Johnnie Dankworth jazz band performed. The venue later hosted wrestling matches and gigs by a new generation of pop groups such as The Who and The Small Faces.

Bingo later arrived and there was a brief revival of roller skating. A Seventies photograph shows the sign “Dancing, bingo, skating, wrestling” above the entrance of the Grade II listed structure which most people knew as The Locarno.

By 1984 bingo’s number was up while time had also been called on its other occupants, wine merchants Brown & Plummer, leaving the once noble landmark to endure decades of neglect

- FOR more than three decades umpteen redevelopment schemes have been earmarked for the building that is now officially known as The Exchange.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel