CHRIS Tarrant, the future presenter of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?, was in brass monkey mode up on top, being exposed to a constant barrage of fresh air. His ears were ringing too. It was as if fellow ex-Brummie residents Black Sabbath were tuning up alongside him.

But inside, I was happy to report, it was far cosier. We were bumping and jolting along at a fair old pace, clip-clopping a well-trodden route while waving with as much regality as we could muster at hundreds and hundreds of people clogging the sides of the road.

I felt like the Queen Mother… only I was supping a pint of Wadworth 6X, careful not to spill any in transit.

It was a strange experience the other day, flicking through a newly published book* to be suddenly confronted with a long forgotten photograph of myself of 32 years ago.

I look a bit of a pillock really, resembling some bumbling, beery, incidental character from the pages of The Pickwick Papers – which was an appropriate look as we were outside The Waggon & Horses at Beckhampton Wednesday, August 1, 1984, was a momentous occasion.

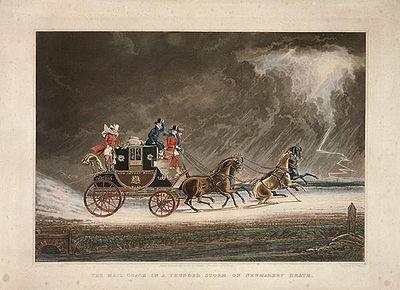

At least it was for the Royal Mail. Exactly 200 years earlier in August 1784 its first ever mail coach – indeed, the world’s first ever mail coach – hit the road.

The pioneering Bristol to London excursion paved the way for the fastest long distance ride-of-the-day, creating a ground-breaking service that lasted more than half-a-century.

The Royal Mail marked the occasion by re-running the inaugural escapade along the same stretch of the king’s highway – now the A4 – complete with a shiny stage coach usually reserved for BBC costume dramas, a la Dickens and Austen, along with some fine steeds to haul the whole shebang along.

Just as it did a couple of centuries earlier, the coach set off from Bristol at 4pm, heading east via traditional mail drop-off/pick-up points such as Bath, Chippenham and Calne to recreate as near as dammit that Billy Whizz-like 131-mile Georgian Jaunt.

I was tasked to cover the spectacular bi-centennial bash for this newspaper and instructed to head for Beckhampton, post-haste.

“So, who’s here from the Swindon Advertiser then,” asked the Royal Mail press officer (which is what they were called in those days).

Oh, it’s me, I responded, from the traditional wooden bar of the splendid and historic hostelry that is The Waggon & Horses.

Next thing I’m being fitted-up with some 18th Century clobber including a Dickensian cloak and a tricorn hat – Dick Turpin chic – much to the amusement of some colleagues who’d tagged along for a laugh and a drink.

Sadly, we were not issued with pistols or blunderbusses to ward off highwaymen as mail guards once were (see panel.) The report which appeared on the front page of the following day’s Adver said: “The grinding of wooden coach wheels, the clattering of horses’ hooves and the stirring blast of a post-horn… it was like something out of a Dickens novel.

“It could have been two centuries ago as the Bristol to London mail coach pulled gamely over the downs.

“Only the constant flashing of camera bulbs and some vehicles of a more modern nature spoiled the illusion…”

Sitting in the carriage with Councillor James Read, the Chairman of Kennet District Council, we were grinning insanely, savouring our 20 magical minutes and waving cheerfully at endless spectators as we clopped from Beckhampton to the next traditional watering hole/coaching inn along-the-line, The Castle and Ball in Marlborough High Street.

Totally exposed to the elements, the seven-mile haul was said to have been the most punishing stage of the entire passage back in the day. “There are many pleasanter places even in this dreary world than Marlborough Downs when it blows hard,” wrote Dickens.

But our quartet of magnificent Hungarian greys managed their leg of the 1984 excursion at a seemingly effortless canter along what was admittedly a far smoother surface.

The reception in Marlborough – and I’m sure it wasn’t entirely for me – was positively carnival-like… as it was at many other towns and villages on the road to London.

Check out the photo of the Royal Mail bi-centenary coach forging through Chippenham and look at the hordes of wildly cheering onlookers encroaching into the road… Tarrant, an old hero from his Saturday morning Tiswas shenanigans, endured a less comfortable outing over several stages of the historic run on top of the rumbling conveyance.

It must have been a hoot up there, what with views and the crowds and the historic vibe. But it became something approaching glacial as the summery August evening evaporated into the chilly dusk.

Not only that, but his aural faculties were receiving a severe and regular trashing, courtesy of coach guard John Drane’s incessant and hearty efforts on post-horn.

“He blows it at every village we pass through,” Tarrant later groaned. “And always right into my ears...”

*Produced by Newsquest Wiltshire, Yesterdays has been published to mark the 200th anniversary of the Advertiser’s sister newspaper the Wiltshire Gazette & Herald, and comprises hundreds of images from its archives. Price £5.95, it is available from 15 Duke Street, Trowbridge, BA14 8EF, Tel: 01225-773600

- BI-CENTENIAL coach driver John Parker, who was in the hot seat for the entire 131 miles, wore out several pairs of gloves grappling with the reins.

The coach arrived at the Postal Headquarters in London on the morning of Thursday, August 2, 1984, 17-and-a-half hours after setting out from Bristol – 30 minutes later than expected.

Two drivers were traditionally used but Mr Parker, 44, completed the trip solo. After a somewhat stiff climb from his seat, he said: “It was like a Christmas card come to life.

“My hands feel like they’ve been put through a mangle. I don’t think it’s a romantic way to travel.

“To look at it, it is. But to ride all night was something else.”

The 96-year-old record for changing four horses on a Royal Mail stage coach in 46 seconds – set by James Selby in 1888 – twice tumbled during the 1984 re-run.

At Pickwick near Chippenham it was broken by a single second before being shattered some hours later at Chiswick in London by five seconds.

- IT wasn’t called The Waggon & Horses then but a young Charles Dickens is known to have stayed there several times while journeying by coach between London and Bath.

His first novel The Pickwick Papers, charting the adventures of a rotund, wealthy, and endearing busybody, was originally published in monthly instalments between 1836 and 1837.

Dickens was inspired to set one of the “stories within the novel” at the thatched 17th Century coaching inn at Beckhampton. The Bagman’s Story is a short yarn concerning commercial traveller Tom Smart – a “bagman” - who stumbled upon the inn “on a raw winter’s night…”

It was, wrote Dickens, “a strange old place built of a kind of shingle…with gabled-topped windows projecting completely over the pathway.”

They are still there today…

- THE instigator of the Bristol-London mail coach was Bath theatre owner John Palmer (1742-1818.) He felt that a fast-track coach service, similar to the one he operated to transport actors and materials, could be adapted by the postal authority.

Ever since Britain’s post service began in 1635, mounted carriers had ridden between “posts,” but the system was inefficient and a frequent target for robbers.

In 1784 the Post Office eventually gave Palmer’s idea a go and undertook a trial run from Bristol to London.

Under the old system the journey had taken up to 38 hours but the coach, funded by Palmer, left Bristol at 4pm on August 2 and arrived in London 16 hours later. THE mail coach was a carriage drawn by four horses that delivered the post in Britain from 1784. Four paying passengers were allowed inside while others were later permitted to sit on top with the driver. The mail was held in a box to the rear next to the guard – the only Post Office employee on board. It was faster than the stage coach as it only stopped to deliver the mail at ‘post houses’ along the way. Passengers were obliged to dismount from the carriage when going up steep hills to spare the horses – as described by Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities. The coaches initially averaged seven to eight mph in the summer and about five mph in winter though they made better time during the early 19th Century as the roads improved.

-

Fresh horses were supplied every ten to 15 miles while mail stops were like pit stops – ‘blink and you miss ’em’ brief.

Sometimes the coaches didn’t stop at all with the guard chucking the mail off the coach and snatching the new deliveries from the postmaster.

Travelling by mail coach was more expensive – a penny a mile – than by private stage coach, but it was faster and generally less crowded and cleaner.

They usually travelled by night to make better speed as the roads were less busy.

In Post Office livery of scarlet and gold, the guard was armed against potential attack from highwaymen with a blunderbuss and two pistols.

He was also issued with a timepiece to ensure the coach was on schedule and a post-horn to alert post houses and tollgate keepers of their imminent arrival.

Any snoozing tollgate keeper who didn’t have the gates open was liable to be fined. The guard was also entitled to honk if a slower coach hampered their progress as the mail had right-of-way.

Mail coaches were phased out during the 1840s and 1850s

- THE instigator of the Bristol-London mail coach was Bath theatre owner John Palmer (1742-1818.) He felt that a fast-track coach service, similar to the one he operated to transport actors and materials, could be adapted by the postal authority.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here