THERE have been whispers of a purpose-built Museum and Art Gallery to replace the original ever since the 'temporary' turned long-term SMAG opened its doors in the early 20th century.

And every few decades or so, the pipe dream would be back on the table, the promise of a shiny cultural hub dangled as a beacon of hope for the art community, only to be scrapped again. Until now.

Concrete plans are in for a £22m ultra modern building to house the museum's feted collection, most of which has never been displayed on the Old Town gallery's hallowed walls. It is no doubt a highly ambitious project with a breath-taking price tag - but a vague castle in the sky, it is no more.

"The museum [in Bath Road] was temporary from the beginning," says Linda Kasmaty, chairman of the Friends of Swindon Museum and Art Gallery.

"This was promised for years and years. And it's been going on behind the scenes for a long time. Seeing the design is a big step."

The concept and blueprint are a major step forward for the committee and tangible proof of what could be achieved - as early as 2021.

But they are also a reminder of the mammoth task ahead. Aside from the immediate concern of securing £10m of Heritage Lottery Funding - after a bid for 12.5m was rejected by the body in 2015 - and persuading the public to dig deep into their own pockets to scrape together £4.5m towards the project, there is the rather tricky matter of convincing the most recalcitrant, at a time when culture is under unprecedented threat (the undignified library closures being a perfect example), that it is not only a viable proposition but could prove a game-changer for the future growth of Swindon.

"We want to start those discussions, see what people have to say, what their objections are and hopefully we'll be able to convert them to the idea," she adds.

"This would just be fabulous for the collection and for the town."

"The time is right and Swindon deserves to be as culturally important as anywhere else," agrees museum director Hadrian Ellory-van Dekker, who was the Science Museum’s head of collections and chief curator before coming on board to head the project back in June.

"And the burgeoning cultural quarters will have a really beneficial impact on the daytime and night-time economy of the area and on the wider town centre."

As part of his role as director, he was given carte blanche to dream up a versatile and multi-purpose "landmark destination" not only for Swindon but the region, able to finally display a significant collection of British modern art, including works by Lucian Freud, Henry Moore, L S Lowry and Graham Sutherland, act as platform for renowned and fledgling local artists and repository for the town's heritage.

The extensive 'wish list' in place, came time to come up a design worthy of Swindon's new cultural quarter, on the site of the old Wyvern carpark.

After a thorough vetting process, the Swindon Museum and Art Gallery Trust chose Make Architects' contemporary butterfly design.

Make’s proposal, created with Arup, Steenson Varming and Alinea, includes learning centres, event spaces, a cafe and dining area, and viewing gallery.

"They've thought about the building and its position in the town, the surrounding buildings - there's Swindon Dance, the Central Library, the Wyvern - in such a way that it's not just a beautiful idea that could have been dropped down anywhere," says Hadrian.

"We didn't want it to be a relocation project and move it into a brand new shiny box.

"The relocation is just a by-product. It's about having a Museum and Art Gallery that has a beneficial impact on the culture, social life and economy of Swindon and becomes a real community space. It all came together. It's really exciting."

Having a solid plan in place, and strong vision backed up by a cutting-edge design, Hadrian explains, will no doubt give the HLF funding application, due to be submitted in November 2017, the weight and substance it lacked the first time around.

Hadrian says: "£10 million is a lot to ask, its one fifth of the national budget, so we had to make sure this time we were ready.

"They rejected the first submission but the HLF are very supportive of what a museum and art gallery can do for the cultural and wider life of Swindon.

"They were really encouraging but they thought that the case hadn't been made strongly enough; so they came back with some very useful feedback and we will be taking it into account as we move forward with our second submission."

All being well the council has pledged £5m towards the project while the Swindon & Wiltshire Local Enterprise Partnership it is poised to plough £1.5m into the venture. The trust will also bid for other grants but the rest will be raised through a huge public appeal, which will launch in January.

Swindon-born artist Ken White has thrown his full support behind a new museum, which he insists, cannot be built soon enough.

"We've been missed out on the cultural map," says the 73-year-old, who was Richard Branson's artist in residence.

"It's the right thing for Swindon. They've been talking about it for years and I want to still be around when it happens."

"It is something that will bring prosperity to the town and it's a win-win for us in Swindon," adds Linda. "If we can get the community behind it, there's no stopping us."

Hidden collection full of forgotten gems

THE Swindon Collection of 20th Century British Art – its official title – was founded by visionaries and carefully nurtured, writes BARRIE HUDSON.

The seed came from a successful Aldbourne-based businessman, HJP Bomford, who in 1941 donated 21 works from his own collection.

According to a family tree prepared by some of his relatives, Herbert James Powell Bomford was born in 1896 and died in 1979.

His career included farming in South Africa, working on the stock market and dealing in property.

He was also a passionate collector of many types of art, and the pieces he gathered can be found not just in the Swindon Collection but also Oxford, Bristol and Australia.

Swindon’s first borough librarian, James Swift, is usually credited with beginning the work of curating and adding to the collection, which has grown to more than 280 pieces.

With the blessing of his bosses, he began acquiring pictures, and early financial support came from a local philanthropist FC Phelps, who also offered some works from his own collection.

These included pieces by Gerald Gardiner, one of the country’s greatest painters of nature subjects.

Swift’s successor was Harold Jolliffe, who served for more than two decades from 1946 and whose legacy includes much of the modern local arts scene. He was instrumental, for example, in the conversion of a Devizes Road dance hall into the Arts Centre, and a prestigious annual theatre festival is named in his honour.

Under Jolliffe’s supervision, the collection steadily expanded. Each purchase was carefully chosen by Jolliffe and his successors.

They remained focused even when their decisions proved controversial, as happened in the 1970s when a piece called Two Walks by Richard Long generated lively debate in the Swindon Advertiser’s letters pages.

The work, now acclaimed as visionary, consists of a map on which the artist drew two straight lines charting the course of walks he had taken. There is also a photograph of a mist-shrouded stone monument which stands at the point where the lines cross.

The artists represented in the collection range from superstars to respected but less famous practitioners.

The former category includes Lucian Freud, whose Girl with Fig Leaf is instantly recognisable.

Other iconic pieces includes Vanessa Bell’s Nude with Poppies, Howard Hodgkin’s Gramophone and Henry Moore’s seated figure.

One piece of art in the collection carries a double dose of local interest, as it was created by one famous Swindonian and shows another.

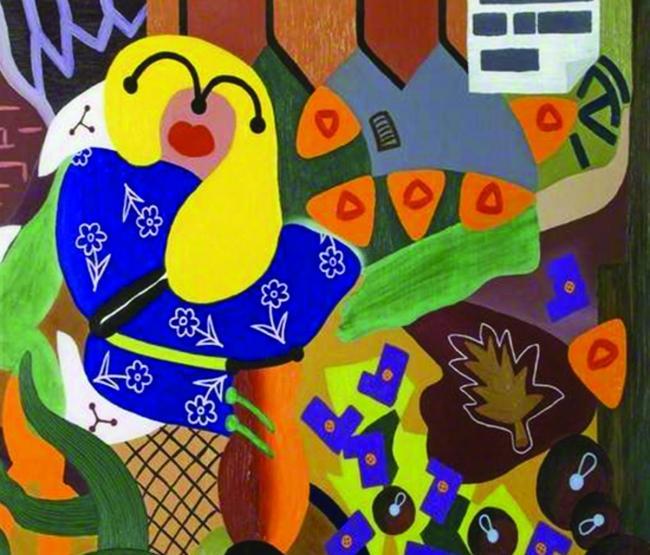

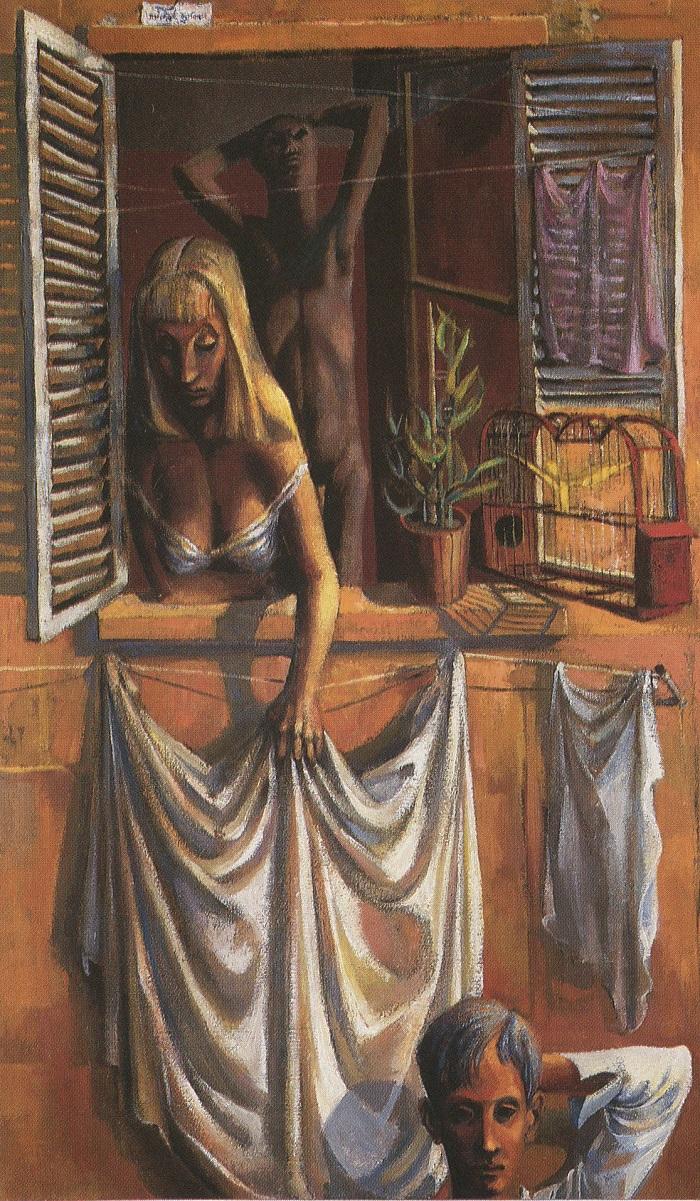

Desmond Morris is best known as a zoologist and author of worldwide non-fiction best sellers such as The Naked Ape and Manwatching.

Few people realise that he is also an acclaimed surrealist painter, whose images of strange life-forms he refers to as biomorphs have won favourable comparisons with the great Joan Miro.

Early in his painting career, when he was just 18, Morris created a piece called Girl Selling Flowers. The young woman is shown in a semi-abstract style, but her shock of blonde hair and ruby-red lips are clearly visible.

The woman was Morris’s girlfriend at the time, a young woman called Diana Fluck who would change her name (to Dors, of course) and do quite well for herself in showbusiness.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel