“DEATH lurks in North Star’s glowing depths,” ran a Swindon Advertiser headline on Monday, October 22, 1973.

In those days the most prominent features above ground there were the old Swindon Group of Hospitals central laundry and the new Swindon College extension.

And below the surface? A quarter of a million imperial tons of burning ash – which covered about 20 acres to a depth of 15 feet.

The buried fuel was a legacy of the site’s previous incarnation as part of the vast railway works complex, when it had been a dump for spent and partially spent fuel.

After remaining inert for decades, the remains had probably been ignited during demolition work in 1960 and burned ever since.

Our headline was no exaggeration.

We said: “Scores of children have been seen playing on the site, which smoulders and steams like the surface of a planet in a science fiction film.

“Old air raid shelters add to its attraction as a playground. Parents seem oblivious of the danger.”

A British Rail technical expert called RR Dallis told us: “The place is a death trap.

“There is serious danger to anyone walking over it. There is a hard crust on top and it is sometimes white hot underneath.”

That crust, he added, might break at any time, plunging the walker two or three feet into the burning material beneath.

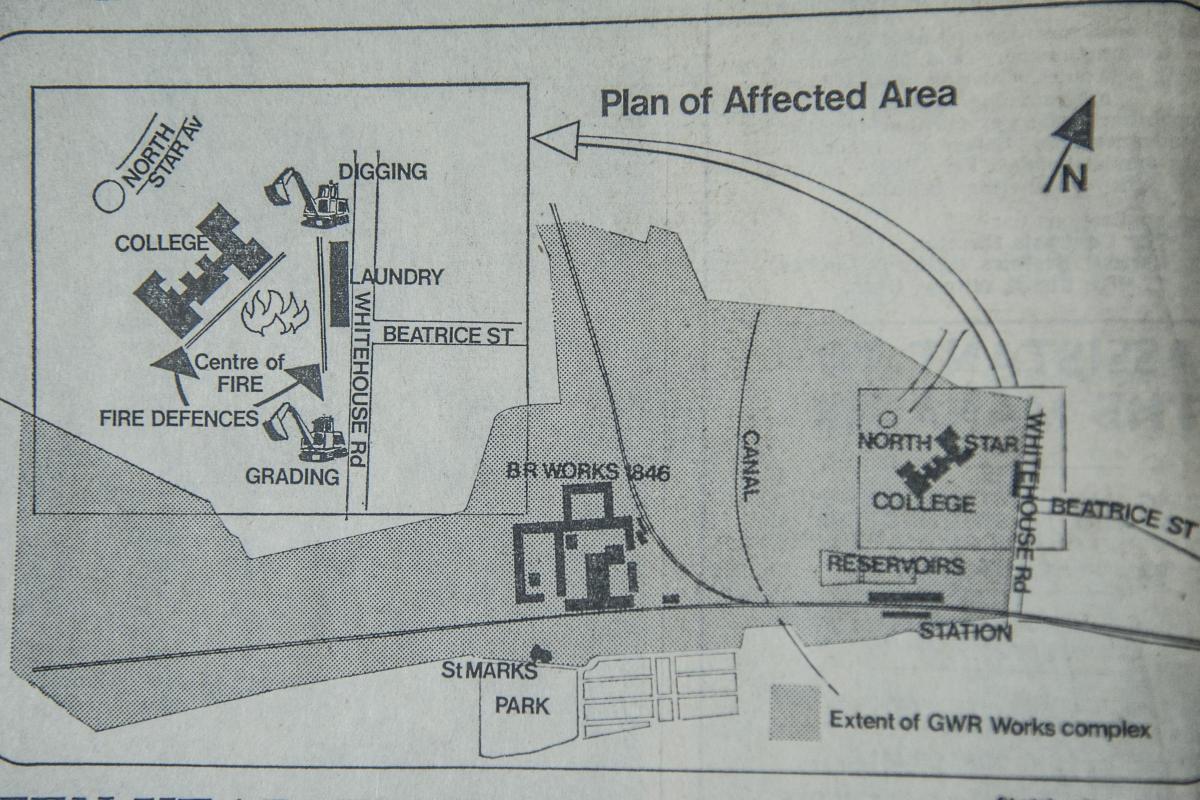

To protect the college building from the hidden inferno, it was fronted by a 400-yard underground concrete wall, 15 feet thick and in places 15 feet tall. A similar fire break had been placed near the laundry.

We printed a helpful diagram of the safety measures.

The story was a little like that of Centralia, the Pennsylvania mining town troubled by a years-long fire in a coal mine, although unlike Centralia there was no need for evacuation.

By October of 1973 a contractor had been employed by the county council to shovel out the dangerous material at North Star, with a bounty paid for each ton disposed of.

Not everybody living and working in the surrounding area was happy, though, and especially not when the wind whipped the freed ash into the air.

A builder working on a house in Beatrice Street reported: “I went home looking like a coal delivery man.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel