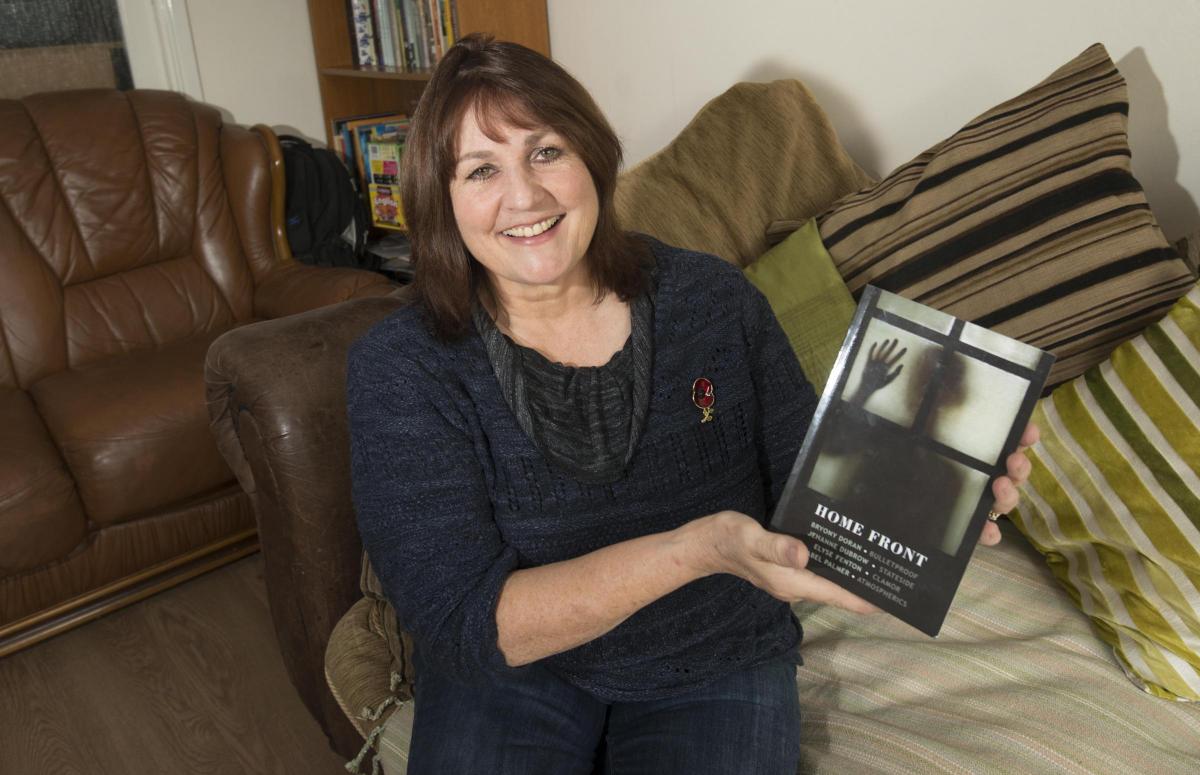

When her son Harry was deployed in Afghanistan, Isabel Palmer from Toothill began to write poems capturing key moments of his tour. Now the co-author of a new book of poetry, Home Front, the 62-year-old recalls her fears, doubts and hope waiting for her son to come home safely.

LIKE most mothers, I had a few ideas about what my son, Harry, might do with his life: a career in sport, marriage and children. Going to war was never one of them.

Admittedly, he joined the Army Reserve at 17 and shared a name, birthday and regiment with my father, who would have been a hundred years old on his twenty-first birthday. However, I didn’t expect that, just three months later, Harry would be a frontline soldier in Afghanistan, leading foot patrols and operating the device for detecting Improvised Explosive Devices, one of the most dangerous jobs in the British Army.

I was proud, of course, but fearful. I had grown up in the shadow of the Second World War. My mother lost her first husband in that conflict, leaving her with a small child, my sister, to bring up. My father and all his brothers fought and all came home damaged - physically, mentally or both. My father’s youngest brother was a Normandy veteran, fighting all the way from Gold Beach through France and Belgium to Berlin. My grandmother died, not knowing if her youngest son would ever come home and, when he did in 1947, he spent a year in hospital with PTSD, which my father always described as ‘trouble with his nerves’. My uncle’s experiences haunted him all his life and, when he returned to France fifty years later, he was still able to point out where all his comrades had been killed by American bombers, as he took cover in a crater. He spent many hours searching for the grave of a young German soldier he’d buried, whom he knew only as Gunther, with his rifle to mark the spot, a story that inspired one of the poems in the collection.

I was fearful too, once Harry had deployed, every time someone knocked on the door: postmen, charity collectors, trick-or-treaters and there is at least one postman who probably changed his round after delivering a parcel that the BFPO handlers had sent back because it contained ‘dangerous items’ – Babybel cheeses. I tried to adopt the soldier’s use of black humour but I was too superstitious and even when, talking to the Welfare Officer at the pre-deployment briefing, I gave him some trivial reason (yoga, the weekly shop) for not being at home to receive bad news any day of the week, he wasn’t sure if I was joking or deranged.

Every Monday of the tour, I packed parcels and wrote a poem: the first to raise his morale and the second to give myself something to focus on, to stop me from following every item of news about the war. It didn’t always work. Writing the poems required me to imagine what he was going through, which rasped my nerves raw. Just as some people see the shapes of doves, dragons, dancing cats in clouds, I saw reminders of war in everything. A donkey in a field reminded me of stories I’d heard that, in Afghanistan, they sometimes tied branches to donkeys’ tails to trigger pressure plates on IEDs. Discarded carrier bags made me think of Harry checking for signs and signals to locals that a bomb had been planted there. His vigilance meant life or death to him and the men following him. My vigilance was my way of willing him to keep safe. Passing a pop-up shop reminded me of the young wife who nearly drove herself mad sending a hundred parcels in one week, mostly cheap decorations, colouring books, pocket-money treats and games. I can only imagine the reaction from her husband’s comrades when he opened them, turning the sand pink with cheap glitter. In any case, the marriage didn’t survive long after the post-tour celebrations.

I wrote poems about key moments in the tour: the airport send-off, the struggle to fit as many useful, funny, uplifting items into a 2kg shoebox parcel, the Medals Parade, places I visited to re-connect with the history and heritage soldiers have always fought to protect: Big Ben, Westminster, Windsor Castle, Kew Gardens, even Downton Abbey and Longleat – anywhere that made his war seem worth fighting. I wrote poems about the difficulties for soldiers of adjusting to civilian life, of the battle shock that affects so many, from my uncle’s generation until today, when it can take eight years for a veteran to seek help. Some poems tell of the often unrecorded victims of war, especially the children and the animals, like sheep and goats with gunshot wounds. Other poems reflect on my father’s war service; others on events that have happened to other soldiers in the last few years: the conviction of a soldier for the murder of an insurgent, the deaths of soldiers on exercises on the Brecon Beacons. One poem describes a repatriation through Royal Wootton Bassett, where everyone was so quiet and still, I could have been looking at a painting.

Along with three other women writers, whose collections feature with mine in the four-poet book, ‘Home Front’, I have tried to tell the truth about what happens to the people left behind in war. My son came back whole but others didn’t come back at all or sustained terrible injuries. I chose to write poems rather than any other form because we are bombarded by the visual impact of war on our TV screens every night. Poems are more private, more personal, and allow time for the details to sink in. I have never seen combat first-hand but writing these poems has allowed me to tell the stories I know about war and what it means.

Home Front will be released on November 11. It contains four poetry collections by women left behind when their sons and husbands went to war.

Home Front, Bloodaxe Books, £12.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here