A century ago, a young unmarried woman called Ella left her rural home in the West Country to work in London, where she met a man and fell pregnant.

Ella returned home to her immigrant German mother, and Ella’s child was integrated into their big family, regarded as the youngest daughter rather than the grand-daughter she truly was.

Ella died soon after – apparently of a broken heart. The identity of the child’s father was never known – though it has been rumoured he was an American.

The illegitimate child was my maternal grandmother, Sybil Ella.

This story must have been common in those times and every family in the country will have similar tales of love and secrecy, of unexpected or missing family members, unknown siblings or lost parents.

What is new in the 21st century is our ability to harness the power of science and the internet to discover more about our families and ancestry, and to connect with members of our wider family all across the globe.

So, when offered the chance to try the Ancestry DNA test I wondered what I might find out about the long line of ancestors behind me, and the web of relatives I am part of.

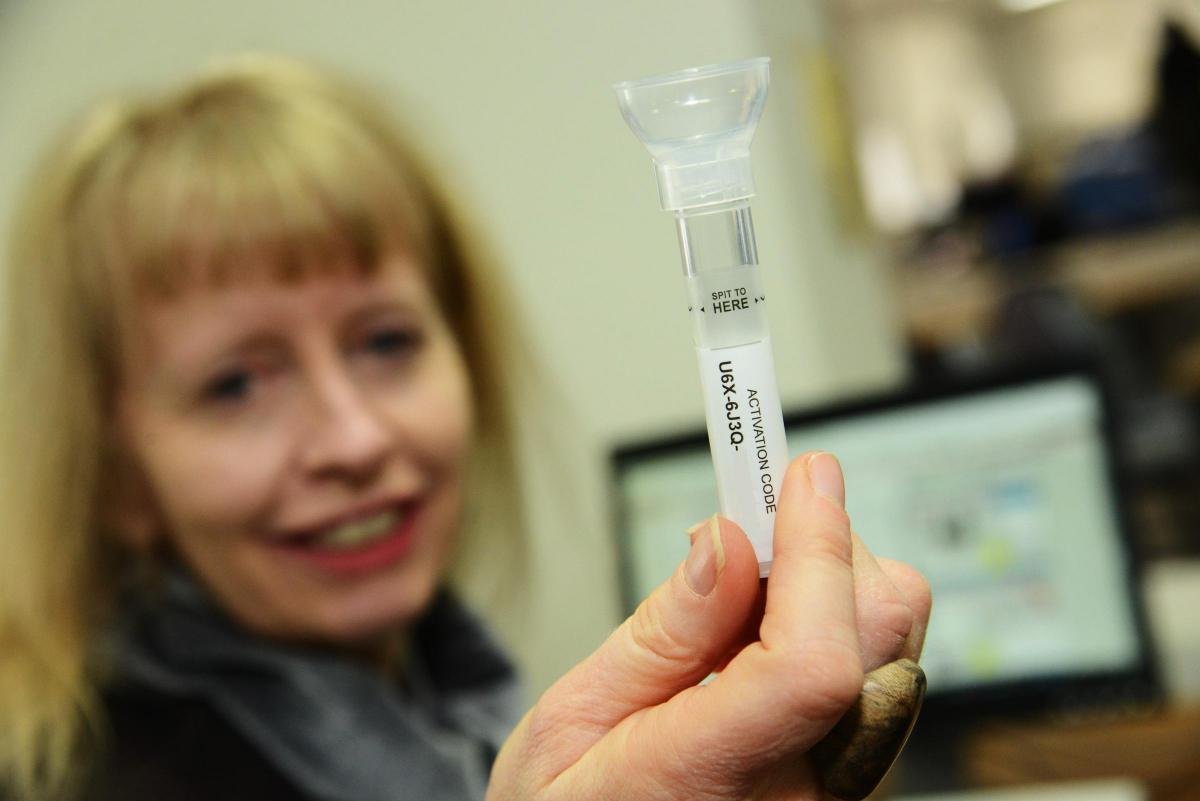

Ancestry DNA sends you a small cardboard box, with a plastic tube and a funnel, and all you have to do is fill the tube with saliva, put it into the small return box, and pop the box into the post. You also have to sign up online with Ancestry, read the permissions carefully and decide how much you wish to be available to other Ancestry members who might be related and wish to get in touch. Then you sit back and wait.

AncestryDNA uses autosomal testing technology to map ethnic origins going back many generations and offers insight into the regions your ancestors are likely to come from.

The process is called microarray-based autosomal DNA testing – which surveys your genome at over 700,000 locations – and uses the data to link you to others who have taken the test.

The company has built a database of genetic profiles for regions around the world, called a reference panel. This panel is made up of people known to have deep-rooted ancestry in a particular area, which creates a genetic profile for a region against which your profile can be compared.

The results of your test may help you make new discoveries about your family’s past or confirm information in your family tree.

It targets your family history over a few hundred or even 1,000 years. Both women and men can take this form of DNA test, unlike some which only analyse the Y-chromosome and follow the paternal lineage, or mitochondrial DNA which only looks at maternal lineage.

It can take six to eight weeks for the results to arrive, but when an email arrives to notify me the results are ready and waiting, I am excited to see what they say.

I log into my AncestryDNA account, and the results are clear to see. The geographical roots of your family are displayed as an easy-to-understand pie chart, with a colour key that links to areas on the map. The map is interactive, so you can click, zoom and find out more details. If you are an Ancestry subscriber you have other options such as linking results to your family tree.

It turns out my ancestry is 62 per cent British, 15 per cent Irish, nine per cent Iberian and eight per cent Scandinavian – with trace amounts (three per cent) from both the Caucasus (the region at the border of Europe and Asia) and southern Europe.

I am not surprised by the Scandinavian link, since (apart from being blonde) my paternal grandfather and his forefathers came from the north-east of England, where they worked in the shipyards, and I can speculate the Scandinavian connection comes from the many incursions of Vikings into the region.

Neither is the significant Irish connection a revelation – but what does impress me about the test results is that zooming in, the Irish result is specific to southern Ireland, and zoom in again, the very south west corner of Ireland, in West Cork.

That is quite amazing – because I know that my great grandparents, Eileen Croft and Duckett Young, did indeed come from that very area. Duckett came from a place called Schull, and Eileen from Bantry Bay. Both were born in the 1880s and emigrated to Britain in the 1900s.

Recent research by my father revealed the sad story that Eileen, his grandmother, later spent decades of her life, never spoken of, in an asylum in Abergavenny, where she died.

I am most surprised by the significant Iberian result. Ancestors from Spain or Portugal?

No immediate candidates spring to mind and I wonder, could this come from my mother’s unidentified grandfather, the maybe American? Who knows?

The topic has, however, generated lots to talk about with my parents and family. It sets up plenty of new questions and presented the tools to find out much more.

Already the test results have offered up the names of several second cousins and third cousins, as well as literally dozens of fourth cousins and beyond from West Cork.

Already I am encouraging other members of my family to take the DNA test. Since everyone inherits 50 per cent of their DNA from each parent, and the assemblage each child inherits is random, this might give us more information.

Perhaps one day it might even enable us to work out who my mother’s missing grandfather was – and introduce us to a whole new branch of the family.

What is so fascinating about the whole process is the complex and moving human story we are all part of, the individual struggles and loves and losses, the migrations and connections, and the links that join us into a great web of relationship with one another.

For more information on finding out more about your own family saga, visit www.ancestry.co.uk.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here