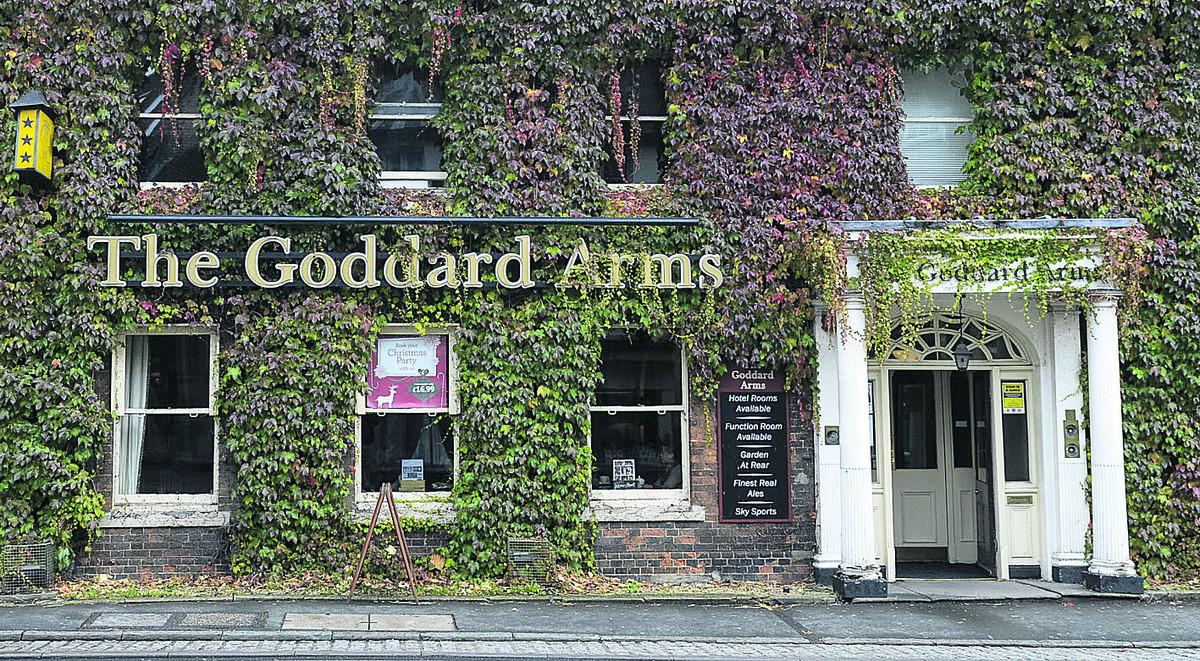

ONE hundred years ago yesterday evening Walter James White, a 22 year-old Swindon house decorator, visited his sweetheart Frances Priscilla Hunter at the Goddard Arms Hotel in Old Town, where she worked as a maid.

Accompanying her to the coalhouse in the yard, he produced a six-chambered revolver, raised it to her face and fired two shots at point blank range. One of the bullets entered her right ear, the other the left-hand side of the neck.

A woman “of quiet and unassuming disposition” Frances, 24, died instantly and – according to her killer – willingly. “For God sake do it then,” she cried to her murderer, and kissed him, said White, seconds before he pulled the trigger.

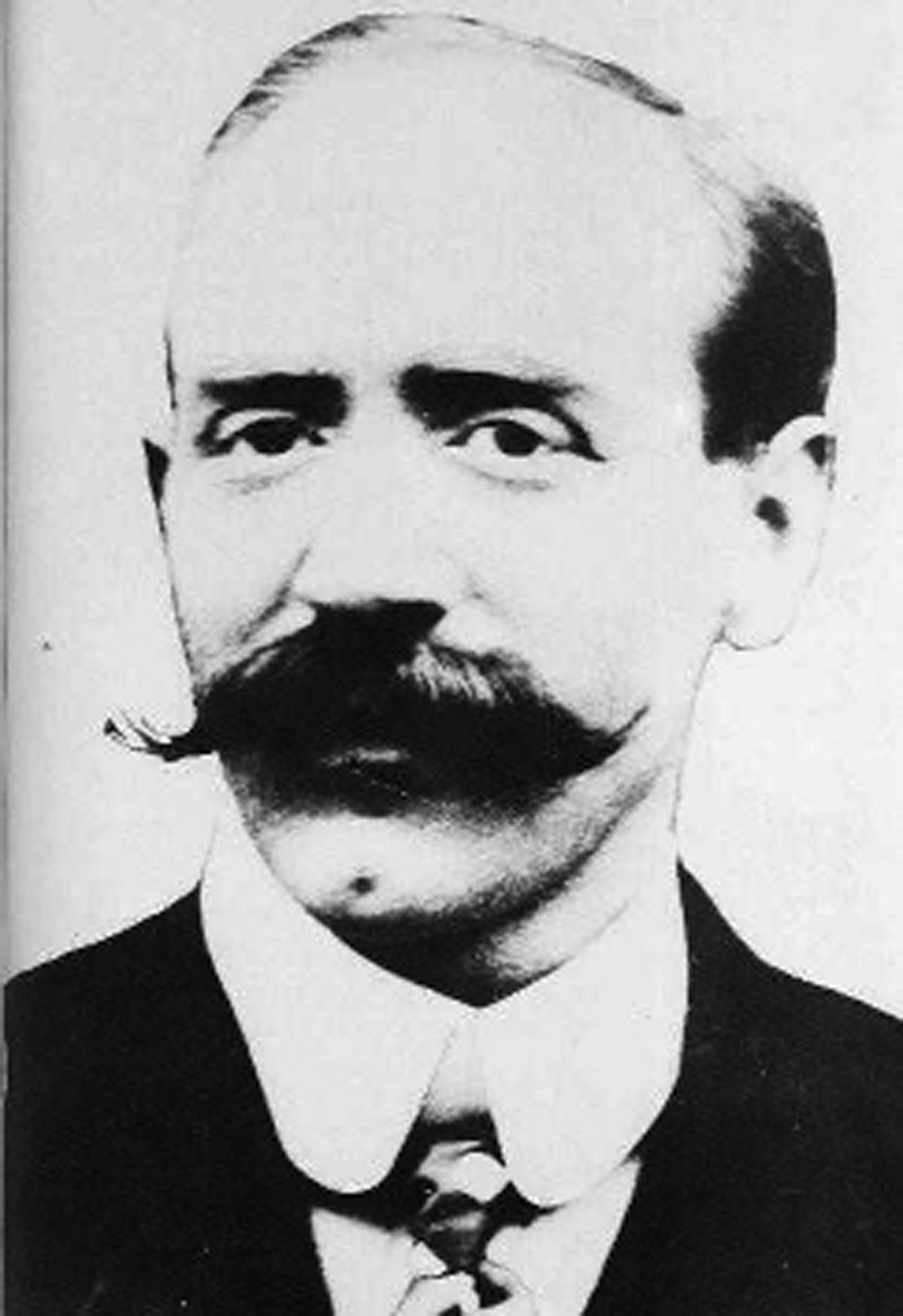

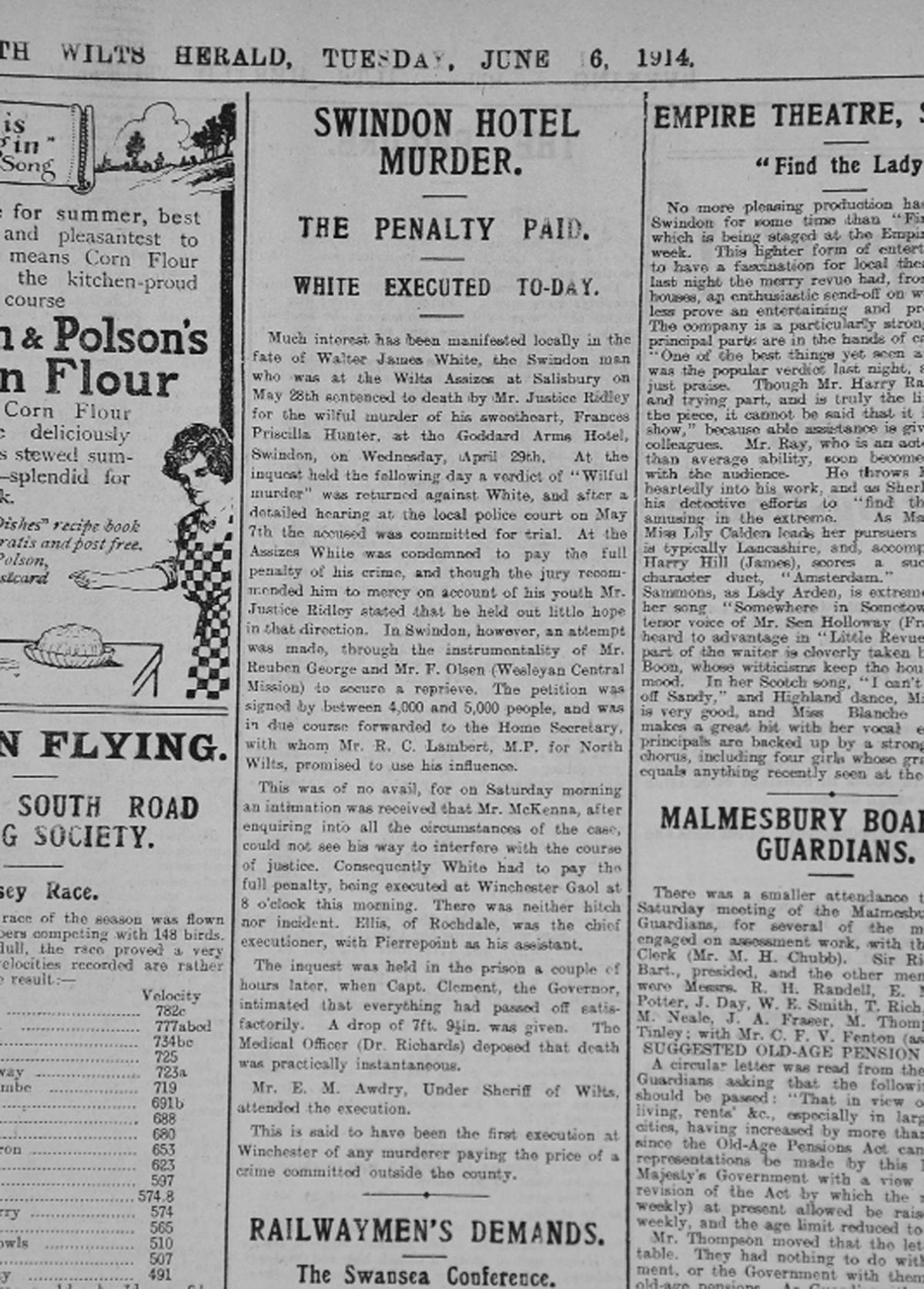

Two hours after dawn broke at Winchester Prison just six weeks later, public executioner John Ellis of Rochdale placed a cloth over White’s head, tightened the noose around his neck and flipped a lever, ensuring a clean and “practically instantaneous death” with a carefully calculated and measured drop of exactly seven feet, nine-and-a-half inches.

As the day of the execution approached the people of Swindon – or, at least, nearly 5,000 of them – signed a petition calling for the intervention of George V to save the young man’s life. However, the young man did not wish his life to be saved and he gladly met his maker. Living would have been unendurable, he had declared.

It was, in every sense, a shocking crime – but also a crime of passion as poignant as any you are likely to see in today’s newspapers, read in a novel or hear in a Johnny Cash murder ballad. This “lamentable affair,” as the Swindon journalist covering the case described it, polarised opinion in a community bracing itself for a world war.

But what prompted an apparently honest, upstanding citizen to murder the woman he intended to marry? It was an act, by today’s standards, that would probably be viewed as fairly commonplace and would hardly register a second thought.

Nearly a year before she met White, Frances had an affair with a married man.

If ever a story demonstrated the difference between morals of life in the early 21st Century to the morals of life in the early 20th Century it is “The Swindon Hotel Tragedy.”

The daughter of Richard Hunter, a Great Western Railway employee, and his wife Mary, Frances lived with her parents at the now demolished Holbrook Street in Swindon town centre. The son of GWR labourer Thomas White, Walter was the youngest of four children, who resided at the family home in Turner Street.

The couple had been keeping company for around six months and the smitten White, described as a “somewhat eccentric” fellow, entertained hopes of an engagement.

On April 25, 1914 they made a fateful trip to the village of Bargoed in South Wales to visit Frances’ two brothers, who were working there, and where she had earlier briefly resided.

At the brothers’ lodgings, White was taken aback when the house keeper, Mrs Eliza Blewitt – who sadly would live up to her name – was disinclined to admit Frances.

She eventually let her into the house but while pouring the tea sternly told the young woman: “Whatever made you bring Mr White here as he is a gentleman. You ought to be ------ ashamed of yourself.”

Frances fled in tears while the upstanding Mrs Blewitt – who, you may conclude, was something of an interfering busy body – immediately felt compelled to write to White telling him “there is something you ought to know.”

White returned to Bargoed four days later where Mrs Blewitt informed him, no doubt believing she was acting in proper and christianly manner, that Frances “had run away with a married man for three months.”

Fifteen months earlier Frances had lived “as man and wife” with a chap called Williams who had employed her as a maid.

“That very much upset me,” White later told the police, as the image of his sweetheart’s chastity and purity lay in tatters. “I could not stand the strain. I loved the poor girl dearly, but she had deceived me.”

White’s reaction was to buy a revolver and a box of cartridges from a general store in Bargoed, catch the next train back to Swindon, write some letters explaining his predicament and, as the evening set in head for The Goddard.

He told police: “I asked Frances if the tale was right. She confessed she had disgraced me and hoped God would forgive her. I told her she would never disgrace anyone else as I was going to kill her.”

Frances’ tearful response, was, according to White: “For God’s sake do it, then! She kissed me goodbye, and I then shot her and waited for somebody to come.”

Frances was found in a pool of blood on the floor of the coal house while hotel manager Amos Church was confronted with the offender firing the gun into the air before coolly asking him to “fetch the police.”

Several letters were found on White, and in one he wrote: “I have been ruined by my sweetheart.”

There were dramatic scenes a few weeks later at the Wiltshire Assizes in Salisbury as White fainted while giving evidence and had to be carried back to his cell. The Times reported that the accused “wept bitterly,” and buried his face in his hands as his statement was read out.

He had committed “a cruel, thought-out and deliberate deed,” said the prosecution. The jury did not buy the defence’s case that White was in “such a perturbed state that he was not responsible.”

The local headlines went: “Swindon Murderer, Sentence of Death, Jury’s Recommendation to Mercy.”

Swindon’s “man of the people” Reuben George, our leading civic figure of the day, mounted a petition to save White from the noose. But Home Secretary Reginald McKenna found no sufficient grounds to advise the King to interfere with the sentence.

At the hour of White’s execution Alderman George received a letter from the prisoner thanking him for his efforts, but saying: “I would have chosen death. I shall go like a soldier and a man.

“If they had granted me a reprieve it would only have been 25 years of suffering, and I shall be more happy where I am going.

“Remember me, but not my shame.”

FINAL FAREWELL

An hour or so before shooting his sweetheart in the face White wrote a letter saying: “My darling mother, brother and sisters I must now tell you that I am going to meet my God.

“I cannot carry this affair any longer. Frances Hunter had ruined me and I hope this will be a lesson to all.

“I hope mother that you will forgive me: I know you will never forget me. But oh, my mind. There is nothing but the grave for me now.

“I cannot face Swindon people again after that. So, goodbye dear mother and all… I cannot bear to face my own respectable brother and sisters again… Goodbye till we meet in peace above.

“Your broken-hearted son, Walter.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here