THE road was crammed with a diverse range of conveyances – from relatively new-fangled motor cars and horse-drawn carriages and carts to bicycles, hundreds of bicycles, many having been breathlessly peddled uphill from the Great Western Railway factory by men who had just clocked off and were frantic not to miss the action.

Others had cycled from towns and villages clustered around Swindon – including one youngster who more than 60 years later recalled in this newspaper perching on his dad’s crossbar during the 12-mile ride from Faringdon.

Thousands more – from elderly folk to mums with babes-in-arms – made their way to the allotted spot by foot on this memorable summer’s evening.

And when they were all there – some 30,000 of them – and it all began to happen, they simply could not contain themselves.

At one climatic point and as though with a single mind, the ecstatic mob charged from the field in which they were gathered to the adjoining meadow, swarming through a hedgerow as if part of some thunderous, migrating herd of wildebeest.

All except one enterprising chap who had shinnied up a railway signal along the Old Town line for a bird’s eye view, while a handful of able-bodied others also sought a better vantage point by scrambling up trees to peer squinty-eyed from the branches.

They were there to see and to greet Henri Salmet whose arrival was destined to become a truly unique and historic occasion in the Annals of Swindon. And the Frenchman, it has to be acknowledged with an appreciative tip of the town’s collective hat, did not disappoint.

His appearance was, to a quote the Swindon Advertiser of more than a century ago, a “beautiful and exhilarating spectacle”.

Attempting to describe Salmet’s miraculous contraption as it honed into town from a great height, our man-at-the-scene wrote that it brought to mind “an enormous dragonfly.”

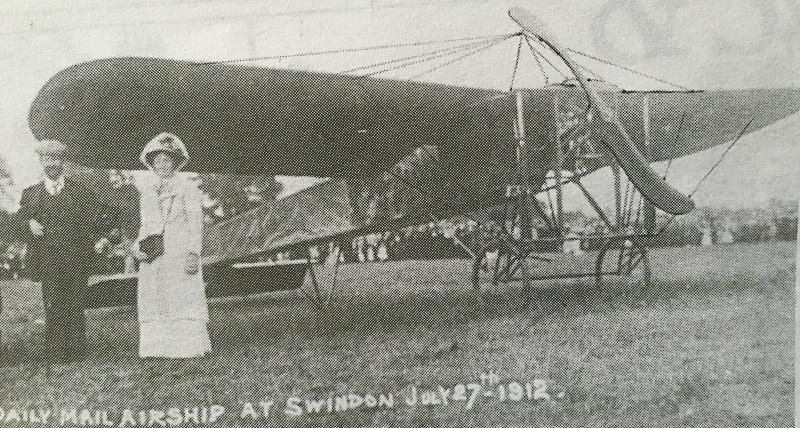

The date – July 27, 1912. The time – around 6.30pm. The occasion – the first aeroplane to land in Swindon. Or at least, the first ‘official’ touch down here… and most certainly the first air display ever given in or near this town.

A buckshee treat for our Edwardian ancestors that none of them were ever likely to forget!

For a town steeped in cutting edge railway innovation and technology, Swindonians were used to witnessing – and indeed, manufacturing – vehicles that were faster, fitter and stronger than those which had gone before but none of these locos actually flew – not in an off-the-ground sense. A Flying Frenchman changed all that… Seven years earlier in 1905, the Wright Brothers, Orville and Wilbur, had built and flown one of history’s greatest inventions – a “practical fixed winged aircraft”.

Fascinated at the thought of attaining flight, Paris-born mechanic Henri Salmet arrived in Britain in 1911 specifically to learn how to fly under the tuition of the French master aviator Pierre Prier, chief instructor at the Blériot Flying School in Hendon.

Henri would later tell a packed, attentive and enthusiastic Empire Theatre in Swindon: “Flying is easy, anyone can do it – it’s easier than steering a car.”

It was just a matter of weeks, then, before Henri, 32, gained his wings at Hendon in the form of an Aviator’s Certificate.

He didn’t hang about. Within a few weeks he broke the British altitude record of more than 8,000ft before shattering his instructor’s non-stop flying record from London (Hendon aerodrome) to Paris – 171 miles/three hours, 16 minutes.

In July and August the following year the personable, showman-like Salmet, with his dashing good looks and slicked aviator moustache, embarked on ground-breaking tour of England to further promote public interest in aviation.

In his two-seater Bleriot XI-2, the Parisian pilot – sponsored by the Daily Mail – visited 121 towns, performing thrilling, never-seen-before-stunts for countless open-mouthed spectators below.

The monoplane maestro’s descent in Swindon, following an appearance at Cirencester, occurred on fields adjoining Coate Road – now Marlborough Road – known as Piper’s Corner (after a local family who once lived there), between today’s Piper’s Way roundabout and Broome Manor Road.

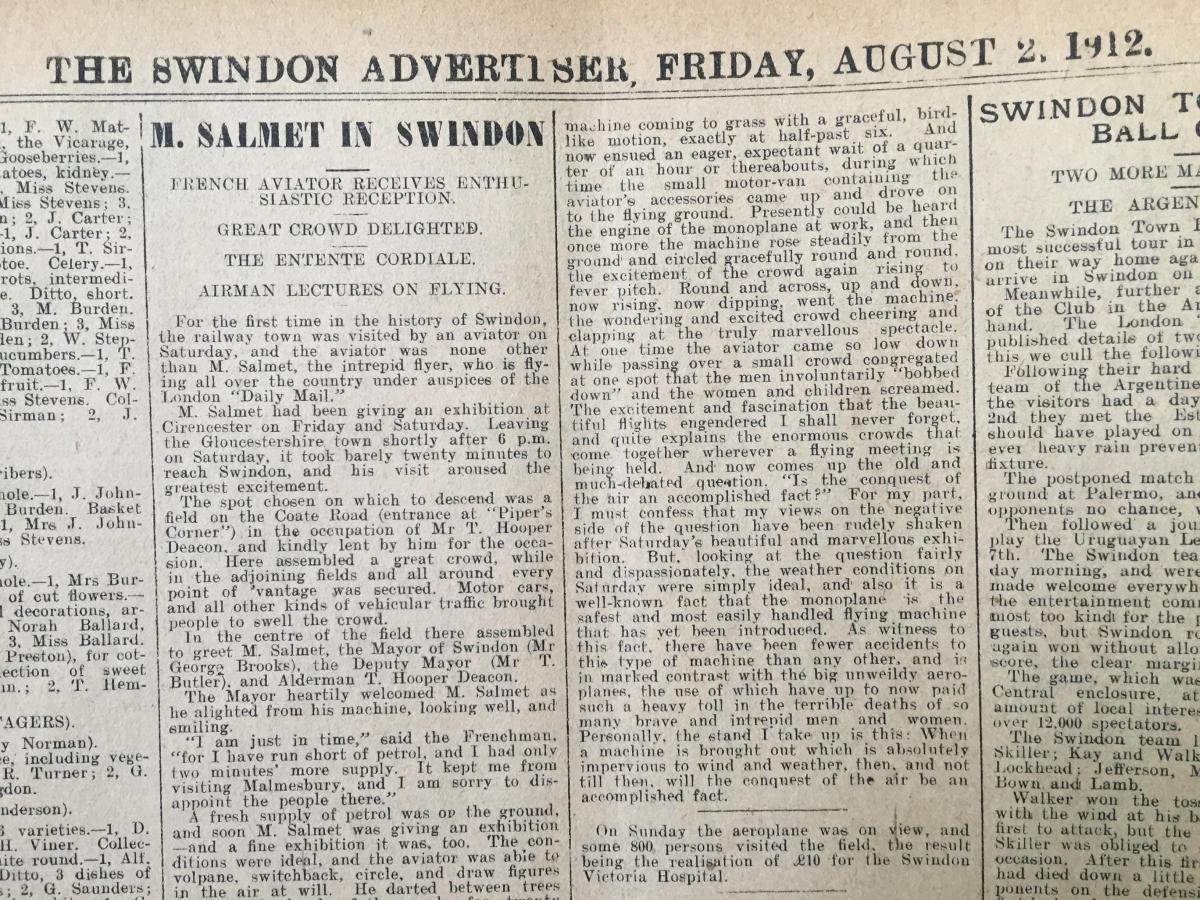

The Advertiser graphically captured the excitement and furore generated by the “intrepid flyer’s” arrival.

Coate Road was a mass of “excited, eagerly expectant people,” we reported, before going on: “The roads were thickly dotted with men, women and children all moving in one direction, together with bicycles by the hundred, motor cars by the dozen and vehicles of every description.”

Scouring the skies for that tell-tale speck in the wide blue yonder, Salmet’s Blériot was spotted at about 6pm.

“As it grew nearer and assumed a shape it gave one the idea of an enormous dragonfly,” our man reported. “The vast crowd grew enormously excited, craning their necks and standing tip-toe to catch a view of the aviator.

“Indeed the excitement was so intense that the crowd broke through the hedge, and hundreds raced across the intervening meadows towards the spot where Monsieur Salmet was to descend.”

The machine we reported, came to grass “with a graceful, bird-like motion at exactly half-past six.”

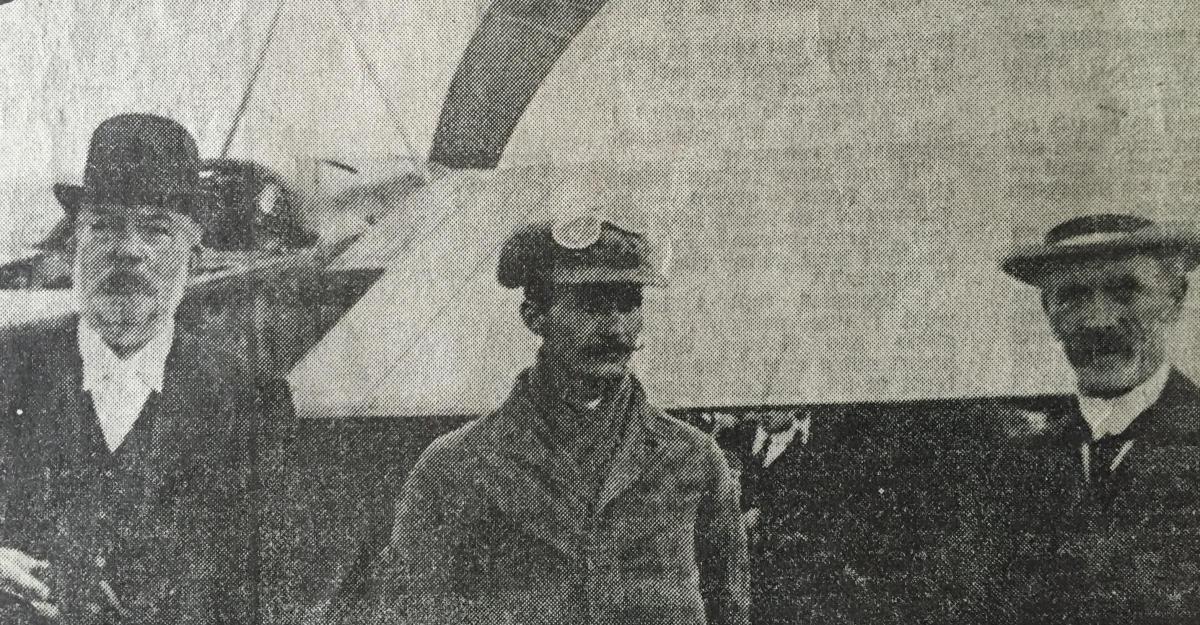

His aircraft was quickly cordoned off before he was officially welcomed to Swindon by Mayor George Brooks and a party of civic worthies. “I’m just in time,” quipped the unflappable Frenchman. “I’ve just run short of petrol and only had two minutes left.”

This forced him to hastily scrap a flying visit to Malmesbury, ironically the home of Britain’s first aviator – Elmer the Flying Monk who chucked himself off the abbey roof strapped to a pair of home-made wings 1000 years earlier before crawling back to the drawing board with a couple of broken legs.

Having refuelled, the natural-born showman – Henri, not Elmer – was airborne again 20 minutes later whereupon he managed to “switchback, circle and draw figures in the air” climbing, circling and diving… pre-dating next month’s Royal International Air Tattoo at Fairford by almost 75 years.

The finale saw the presumably grinning Salmet “dart through trees” and swoop just above the heads of the enthralled masses. No elf’n’safety back then.

“They laughed and cheered themselves hoarse,” said the Adver.

Was Henri Salmet's plane the first over Swindon

TIME can plays tricks with the memory and perhaps this is why 63 years after Salmet’s dramatic descent our more mature readers were busily debating whether his flimsy Bleriot XI-2 really was the first plane to land in and fly over Swindon.

The Adver of August 2, 1912, had no doubt. “For the first time in the history of Swindon the railway town was visited by an aviator.”

But in 1975 reader Bert Wilks asserted that an aircraft had sailed over town a year before the go-cart like wheels of Henri’s aircraft hit our green fields.

However, his pal HV Osborne of Exeter Street reckoned a bi-plane landed at Coate as early as 1908, recalling that his brother and a pair of school-chums saw the huge “box kite” like object dip and touch down.

“Within half-an-hour of it landing there were upwards of 1,000 people in the field,” he informed us.

He was convinced the pilot was none other than pioneering German/British aviator Gustave Hamel who vanished in an aircraft over the English Channel, aged 25, in May, 1914.

However, a flying visit to Wikipedia – which was not available to Mr Osborne, alas, in 1975 – reveals that Hamel never learnt to fly until 1910.

AG Harris, of Purton, was quick to poo-poo HV’s contention 41 years ago, insisting that famed aviator Samuel Franklin Cody, the first man to pilot a powered, sustained flight in Britain in 1908 was the mysterious Coate flyer.

Almost year after Salmet’s celebrated arrival, two men in a monoplane underwent a somewhat less than dignified experience at Lydiard Tregoze.

Taking off on May 10, 1913, their aircraft clattered firmly onto terra firma having turned a somersault while attempting to lift-off.

Its’ occupants from the Netheravon Flying School staggered away dazed, relieved and largely unscathed.

Laughter as Henri Salmet tells Swindonians of his exploits

HAVING left Swindonians wide-eyed and breathless, Henri Salmet pointed his flimsy Blériot northwards to perform some whirls and twirls over Blunsdon before returning to Old Town.

At some stage he dropped a letter over Swindon containing the words Entente Cordiale, denoting a friendlier understanding between France and Britain.

It floated gently towards the garden of Adver reader WJ Hatter of St Paul’s Street, Gorse Hill who professed to have caught it before it reached his lawn.

A few hours later Henri was holding court at Swindon’s now long demolished Empire Theatre cheerfully regaling the audience with tales of aeronautical adventure.

“When I’m in my machine,” he explained in broken English.

“I’m much more safe than you are in your motor cars. There’s no dust, no dangerous corners and the police can’t say ‘you go too fast’.”

Amidst hoots of laughter, the affable aviator told how he shattered the British altitude record of more than 8,000ft just two months after learning how to fly.

“It took me one hour, 15 minutes to go up… then my carburettor froze and I came down in ten minutes.”

What happened next...

FOLLOWING his exploits during the Wake Up England tour of 1912, Henri Salmet undertook a similar escapades with the additional attraction of some bonus landings in a water-plane.

In October 1913, Salmet displayed his trusty Bleriot XI-2, and also operated passenger flights in the two-seater, during the build-up to the Wars of the Roses air race in Yorkshire between an Avro bi-plane and a Blackburn mono-plane. (The mono won.) After the outbreak of war, he joined the French Army Air Service flying reconnaissance bombers for which he was twice cited for his actions.

One citation said: “This impulsive and audacious pilot did not hesitate on a scouting expedition to approach a German warplane within 37 yards, so as to permit the observer to shoot at it.”

Another told how the recipient of the French Military Medal “fulfilled many perilous missions, showing the greatest coolness under critical conditions.

“On August 23 1915, flying alone, he dropped 30 shells on an important railway station beyond the Rhine. Overtaken by fog, he returned by compass and landed safely on French soil.”

Sadly Salmet appears to have flown into obscurity following the war.

However, one unconfirmed report says that he died in 1929 aged 51.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article