He may struggle to communicate but former semi-pro footballer Colin Moss, 65, from Foxhill, won’t let motor neurone disease silence him. Here, he opens up to MARION SAUVEBOIS about his daily battle for independence and dignity

I remember looking into a mirror and thinking, ‘I look OK and I am not ready to die yet’.

I will always remember too, what my brother Alan said to me when I first told him I had motor neurone disease and there was no cure: ‘One day they will find a cure; you just need to make sure you are still here when they do!’

Whilst I have gained much experience of MND and suffered most of the effects, I am not a typical case - I have had much slower progression than average.

I was diagnosed in January 2002; which means I am one of only approximately 10 per cent who have survived beyond 10 years. I consider myself very fortunate to be one of the longer survivors.

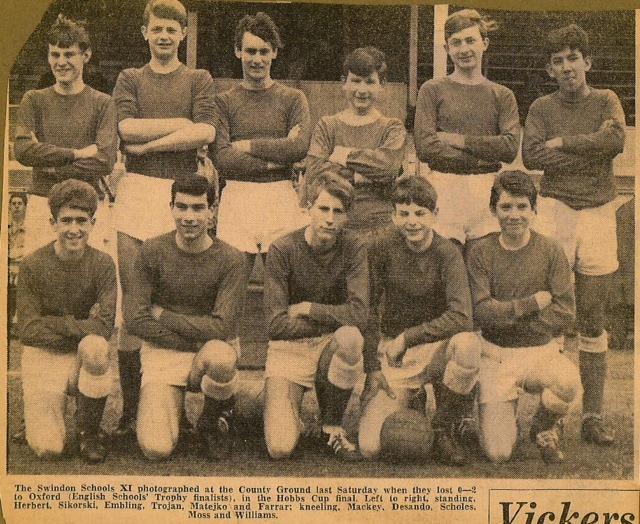

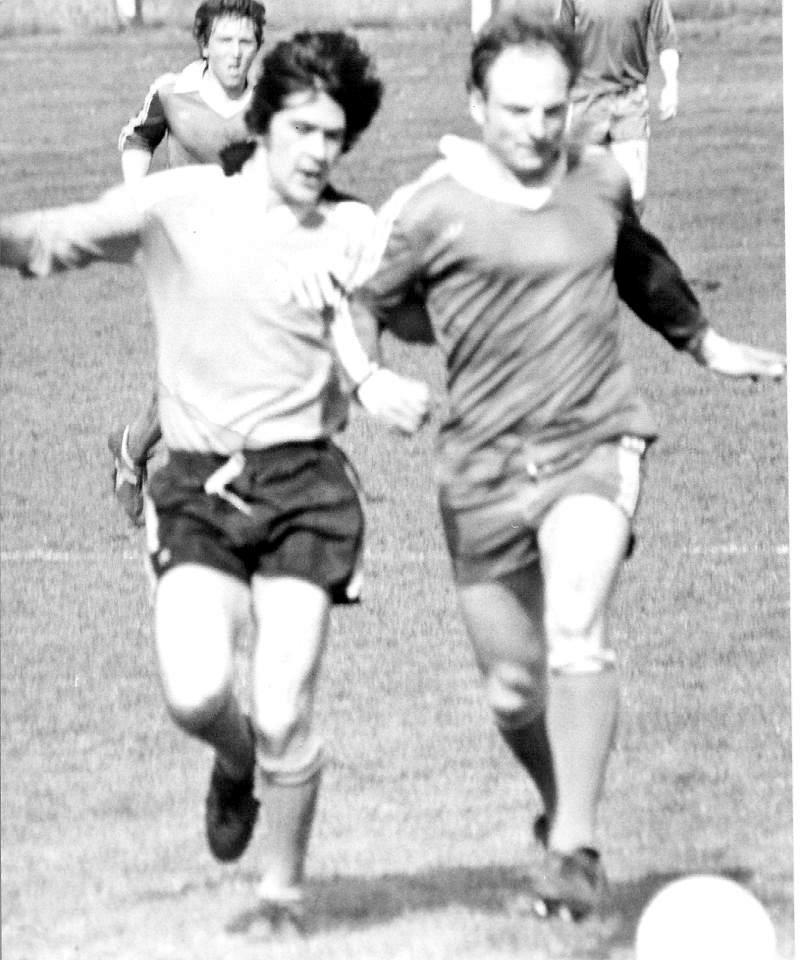

Before MND, I was still very fit and a keen sportsman. I played semi-pro football for Andover and as an amateur for Devizes Town, Chippenham Town and Wiltshire. I finally retired from football at the age of 48, less than three years before I was diagnosed with MND.

The first indication that all was not well was when I noticed very slight co-ordination problems such as having to think about which foot to lead with when stepping over a kerb. I tended to drag my foot a little and had difficulty running. I also realised I had lost the ability to sing in tune.

A few months later I noticed fasciculations - muscle twitching - in my legs and went to my GP. He immediately referred me to a neurologist in Reading who, after examining me, said he was concerned that I may have something that he wouldn’t be able to treat. He arranged an MRI scan and EMG tests and about a week later gave me the news that I had MND.

It was a massive shock to be told the average life expectancy was only around 14 months from diagnosis and that 50 per cent of people with MND died within two to five years from the onset of symptoms.

I suffered from fasciculations, muscle cramps and areas of muscle atrophy very early on, particularly affecting my calves and ankle movements.

I had several falls, two of which required visits to A&E to stitch up head wounds, but thankfully no broken bones and I gradually became more adept at falling without hurting myself.

Within two years I needed a foot brace and started using a walking stick. The distance I could walk and the time I could stand up reduced quite rapidly despite the fact I was still exercising. I also suddenly lost the ability to lift my right arm above my waist.

For about 15 months after diagnosis I managed to continue my work as a project leader of a mechanical design team but, by the end of 2003, I was struggling to even write or stand up for more than about three minutes without needing to sit.

I had purchased a transportable mobility scooter, that, at the time I could disassemble and lift into my car but as time went on I required help. By 2007, I was retired, divorced and had moved house. I was no longer able to walk safely using a stick and had to use a rollator. The only way I could climb stairs by 2008 was to crawl up on all fours.

Fortunately for me I met my present partner Shan and we moved back from Newbury to my birthplace, Swindon, in 2010. We had to install a stair lift and various other aids such as grab rails and shower stool.

Courtesy of the MND Association we also replaced the toilet seat in our cloakroom with a bio bidet to help maintain my independence and dignity.

By 2012, I started to struggle breathing, particularly lying down at night. This led to a few panic attacks, which was very scary. I learned to control these by using distraction techniques, fans and decongestant sprays.

In summer of 2013 I had a PEG feeding tube fitted to supplement my food intake as my swallowing had worsened. I can still eat and drink with care but eating a meal takes much longer.

Speaking has become much more difficult over the past three years too. My speech is hampered further by the fact that MND affects the part of my brain that controls my emotions. This can lead to mixed or excessive emotions - laughing or crying inappropriately. This is called emotional lability.

My mobility continues to decline very slowly but surely. For safety I now use a power wheelchair all the time, although I am still able to transfer and shower independently.

Over the past two years I have suffered progressively with insomnia and sleeping discomfort. I often awake with a dry mouth and struggling to breathe. I overcome this by drinking water from a bottle on my bedside table and using the fan and Shan opens the window or door to let fresh air in. I have a ventilator but would have to wake Shan

each time to put the mask on or take it off, which is not ideal as the mask itself can set off a panic attack.

Whilst I accept there is nothing I can do once the signals to the muscles are lost, I work on the basis that the stronger I can keep my healthy muscles the better I can overcome the weak ones.

I think my ability to stay fairly calm and remain positive has helped me to cope.

The fact that I have received fantastic support from my partner and our families and friends makes a huge difference too.

In contrast to my ex-wife, Shan is totally supportive of me and if it wasn’t for her help I would need to employ a carer virtually full time now.

But over the years I have become increasingly frustrated by my physical decline and not being able to do the things I once enjoyed such as playing football, golf, tennis and snooker or even just walking through the countryside or swimming. There have been a couple of studies into a possible link between football and MND. And there was an exceptional incidence of Italian pro-footballers with the condition. But the causes are not known although it is thought to be a combination of certain genes and environmental factors.

I used to love looking after my classic cars, gardening, decorating and DIY. What really irks me is the need to pay other people to do jobs I used to enjoy doing myself. Having said all that I have realised that there is no point worrying about things I can do nothing about. MND has taught me to make the most of every day and appreciate life more. It has also given me the chance to meet two members of the royal family and learn a new skill - I took up oil painting at Prospect Hospice day care centre.

Despite my frustrations, to date I still enjoy a quality of life - although this will change if I become unable to transfer or if my left arm weakens; in which case I would lose all my independence. Or if I lose my speech completely and my breathing deteriorates further. Although I try to put these thoughts to the back of my mind I am dreading what may lie ahead.

What is MND?

· MND is a fatal, rapidly progressing disease that affects the brain and spinal cord.

· It attacks the nerves that control movement so muscles no longer work. MND does not usually affect the senses (sight, sound and feeling)

· It can leave people locked in a failing body, unable to move, talk and eventually breathe.

· Some people may experience changes in thinking and behaviour, with a proportion experiencing a rare form of dementia.

· It kills a third of people within a year and more than half within two years of diagnosis.

· Six people per day are diagnosed with MND in the UK.

· It affects up to 5,000 adults in the UK at any one time.

· It kills six people per day in the UK, just under 2,200 per year

· It has no cure.

For more information about MND go to www.mndassociation.org.

Colin's friend Tony Vines will be running the Loch Ness Marathon on his behalf to raise funds for the North Wiltshire branch of the MND Association. To make a donation go to www.justgiving.com/fundraising/COLIN-MOSS4

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel