“THERE it was - a complete health service!

“All we had to do was expand it to cater for the entire nation.”

So said Aneurin Bevan, the Minister for Health who oversaw the birth of the NHS, as he recalled a series of visits to Swindon.

The scheme which inspired Bevan and his colleagues was already older than the health service is now.

The GWR Medical Fund Society was founded in 1847 by workers and management of the railway company.

Opinions vary as to whether the bulk of the impetus came from bosses or their staff, but according to late and much respected Swindon author and historian Trevor Cockbill the latter were the driving force.

Interviewed when the NHS marked its 50th anniversary, he said: “The credit for the Great Western Medical Fund Society rests almost entirely with its workers.”

Another expert interviewed for that occasion was Tim Bryan, an author and founding manager of Steam.

He said: “The railway works changed Swindon dramatically. They took it from a small market town to an industrial complex.

“And the medical fund grew out of a determination for workers to look after themselves. It was an organic thing. The workers had to create their own health service. It’s a great example of self-help, and the NHS made that available to everyone.”

In the mid-9th century, life for manual workers in industry was tough and dangerous, and medicine fairly primitive.

Something as trivial by today’s standards as an infected cut or even a bout of flu might prove fatal.

When injury or illness kept people from working, they and their families had little option but to rely on charity.

There was a widespread – and justified – horror of the workhouse, where desperate people and their loved ones were split up and subjected to grim regimes in exchange for food and shelter.

The GWR Medical Fund Society grew from an earlier organisation, the Yard Club, organised by workers who chipped in part of their wage to pay doctors’ fees for colleagues who were laid off when times were hard.

That scheme came to the attention of locomotive, carriage and wagon superintendent Daniel Gooch, who urged directors to provide company doctor Stuart Rea with a rent-free house in exchange for providing unemployed men with medical care.

The doctor was the company’s first medical officer, and his brother, Minard, was Gooch’s first pupil.

Although they both died of tuberculosis in their thirties, they played a major role in establishing the medical fund society.

Railway workers agreed to put deductions from their wages toward medical care for themselves and their families.

The deductions were intended to be affordable. A married man earning more than £1 a week, for example, would pay four old pence, the equivalent of less than two percent of his wage.

According to Mr Cockbill, GWR workers became the committee stalwarts who pushed the society to ever greater achievements.

The GWR itself had a more enlightened approach than many Victorian employers, and certainly realised that a healthy workforce was a profit-generating workforce.

In addition, Daniel Gooch publicly stated that he had a moral responsibility for the wellbeing of workers.

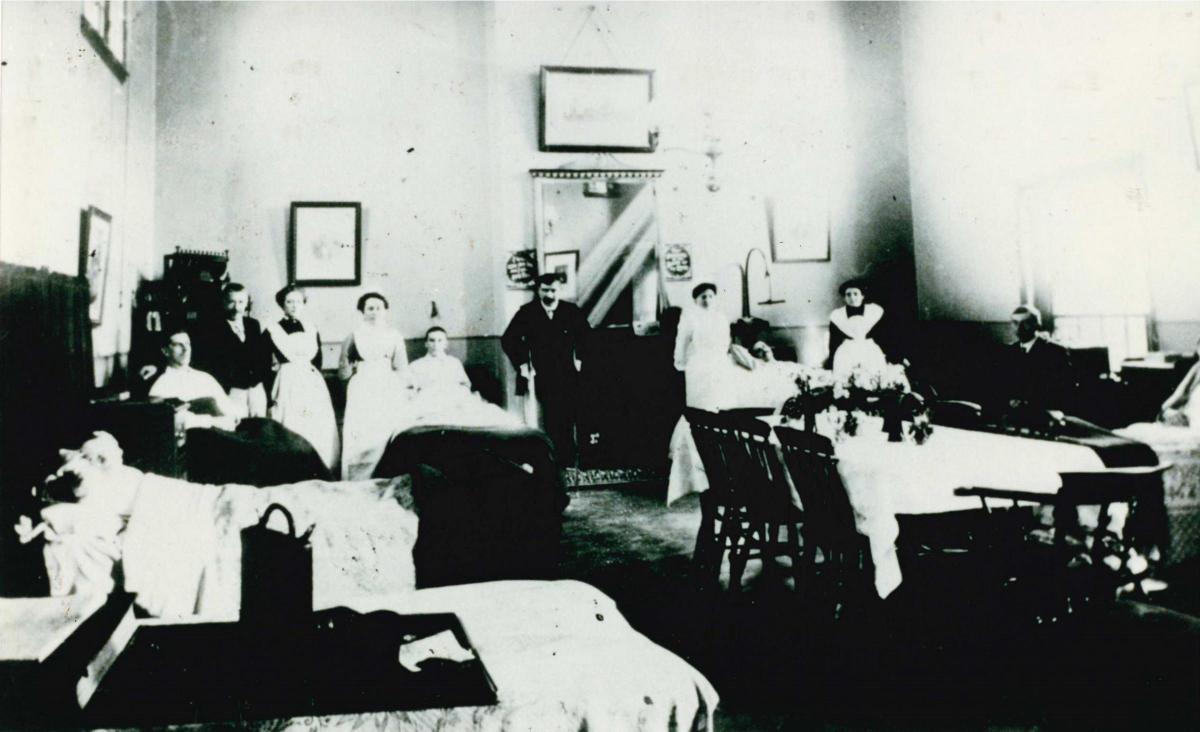

The company’s early contributions to that wellbeing included handing over the old Volunteer Force Armoury and three cottages to be converted into the society’s cottage hospital.

Opened in 1971, the hospital treated patients until the 1960s, and the structure is now the Central Community Centre.

The nearby building now known as the Health Hydro followed in 1891.

More than half a century before most people, let alone people from ordinary backgrounds, had any idea of what a health centre was or why using one might be beneficial, railway workers had reliable washing facilities and a place to exercise and receive medicine.

In an era when maternity hospitals were usually reserved for people who could afford them, railway workers’ wives experiencing difficult births were cared for at a house in Milton Road.

It is little wonder that Bevan and his colleagues were so impressed all those years later.

As Tim Bryan said of the works: “The men who worked there say it was a hard place to work, but most of them say it was the best place they ever worked because of the camaraderie and sense of community.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel