MARION SAUVEBOIS talks to the recently appointed coordinator helping with the demands of Motor Neurone Disease and its consequences for patients

FROM the root cause to its relentless progression, motor neurone disease remains a cruel mystery – not least to GPs and nurses across the world.

While patients and neurologists are getting to grips with the crippling march of the condition, and despite the ground broken by the Ice Bucket Challenge to raise awareness of the fatal disease or high-profile sufferers like Stephen Hawking, the medical profession is still largely ignorant of the debilitating symptoms, scrambling to support patients and leaving families to muddle through virtually alone.

But there is no room for error; and, with a disease which kills a third of patients within a year, time is of the essence to ensure they spend their final months as comfortably and independently as possible.

Now, in a pioneering move, the Motor Neurone Disease Association has appointed Swindon’s very first MND clinical care co-ordinator to train and educate health professionals in the town and ease sufferers’ burden.

Dorinda Moffatt has only just taken up her post but is already breathing a fresh wind of change through the town, spreading the word about the disease and putting a solid structure in place to make sure practical help, and the right equipment, are available to families struggling to cope with a loved one’s rapid loss of movement and eventual paralysis.

“Because MND is progressive you must always be one step ahead. My role is to know what’s out there and make sure people with MND know what is available to them, the equipment they will need before it’s too late,” says the 36-year-old physiotherapist.

“And my role is also to help healthcare professionals with their caseload – it could be a GP, an occupational therapist, physiotherapist, community nurse. Many GPs will see only one person with MND in their career and they’re not familiar with the disease. I’m their port of call for support.”

MND is a fatal, rapidly progressing disease which attacks the nerves that control movement so muscles no longer work. It leaves people locked in a failing body, unable to move, talk and eventually breathe. It kills more than half of patients within two years of diagnosis. There are currently 27 people with MND in Swindon and Wiltshire.

The MND Association chose Swindon for the year-long pilot because of its relatively limited and sporadic access to community support. While there is expert help available at the Great Western Hospital, GPs, physios, nurses and a number of healthcare professionals on the ground are far less likely to have encountered MND, let alone have any in-depth knowledge or understanding of the condition.

The charity used a share of the funds raised through the Ice Bucket Challenge and commissioned Swindon-based social enterprise SEQOL to appoint a coordinator.

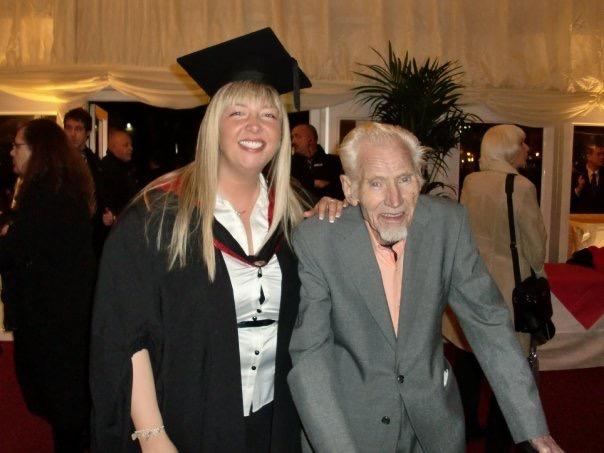

Dorinda, who lost her father and aunt to MND, has more experience of the condition than most.

She was just 15 when her father John was diagnosed and supported him through his steady deterioration. He was initially given two years to live but survived 16. He died in 2011 aged 81.

Her personal ordeal prompted her to devote her life to caring for others and assisting people going through lengthy physical rehabilitation. She trained as a physiotherapist and worked at the Great Western Hospital before joining Prospect Hospice six years ago.

The co-ordinator post is funded for two-and-a-half days a week and she continues to work as a physio at the hospice the rest of the time. Alongside her busy roles she is taking a masters module online with Birmingham University in specialist practice and MND.

As part of the role, she is training and sharing her expertise with community nurses, and any other therapists who may be called upon to support someone with MND to help them manage patients’ complex needs including respiratory problems and panic attacks – which could in turn reduce the number of unplanned hospital admissions.

Much of her work involves making minor alterations to care routines, flagging up useful information or services and arming teams with simple checklists.

While MND is a highly complicated and rare condition, a large part of helping patients requires relatively common-sense steps from healthcare professionals – provided they know what is required of them.

“It doesn’t have to be very technical,” explains Dorinda, who raised £570 for the North Wiltshire branch of the MND Association at the Swansea Half Marathon in June. “But, if they have had no experience of MND, it’s just things they would not know, or had have any need to know.”

Changing negative perceptions of MND and assuaging GP and nurses’ fears is also key for Dorinda. “It’s not just with MND, but any kind of neurological condition,” she adds. “A lot of the feedback I’ve had is that healthcare professionals can be worried supporting people with MND; they are not sure how to deal with it or with respiratory problems, or know how to react to a panic attack. It can be terrifying.”

Shan Mills and her partner Colin Moss, who has been living with MND for 14 years, have experienced their fair share of prejudice or lack of empathy from professionals.

“People with MND often get a bad rap, they’re labelled as challenging or awkward,” says Shan from Foxhill.

“They don’t understand what it’s like, how annoying it is not to be able to use your arm, or scratch your nose, do basic things we take for granted. MND takes over your life; it’s not easy.”

Tireless campaigning from the North Wiltshire group of the Motor Neurone Disease Association was instrumental in securing a coordinator for Swindon. Among those who pushed for more community support is Heather Smith, from North Swindon, who lost her partner Steve Atkinson to MND back in 2012. He died less than three years after being diagnosed, at the age of 51.

She did not seek help at the time, choosing to care for Steve herself, but she admits co-ordinating doctors’ appointments, home alterations while still working was a struggle. Like her, most partners are thrust into a caring role and forced to learn on the hoof – constantly trying to stay one step ahead of the condition.

“As a carer you become project manager,” confides the 42-year-old access specialist at the National Trust.

“You have all these individuals – the GP, occupational therapist — you have to coordinate, you have appointments — and if they don’t know much about MND you have to deal with their reaction. Then you have all the things you need to alter in the house. It’s not like it’s done forever; that first adaptation might not work in a couple of months. It’s constant.

“We really wanted to get someone in post to help with this co-ordinating. To help people so they don’t end up in the position myself and others were in and make sure health and social care professionals are given support and more confidence to work with families with MND. We pushed for it for a long time and it’s brilliant we finally got there.”

But bringing about lasting change in Swindon in just under a year is a tall order.

“It’s not a lot of time to do it,” concedes Dorinda. “But there are things we can start doing straight away – raising awareness, education. It is my chance to do something to help.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here