IT was in the mid-1990s that work on the North Swindon moved into high gear.

The best part of a decade earlier, in 1986, the group of house builders who formed an organisation called the Haydon Development Group issued a brochure outlining their plans.

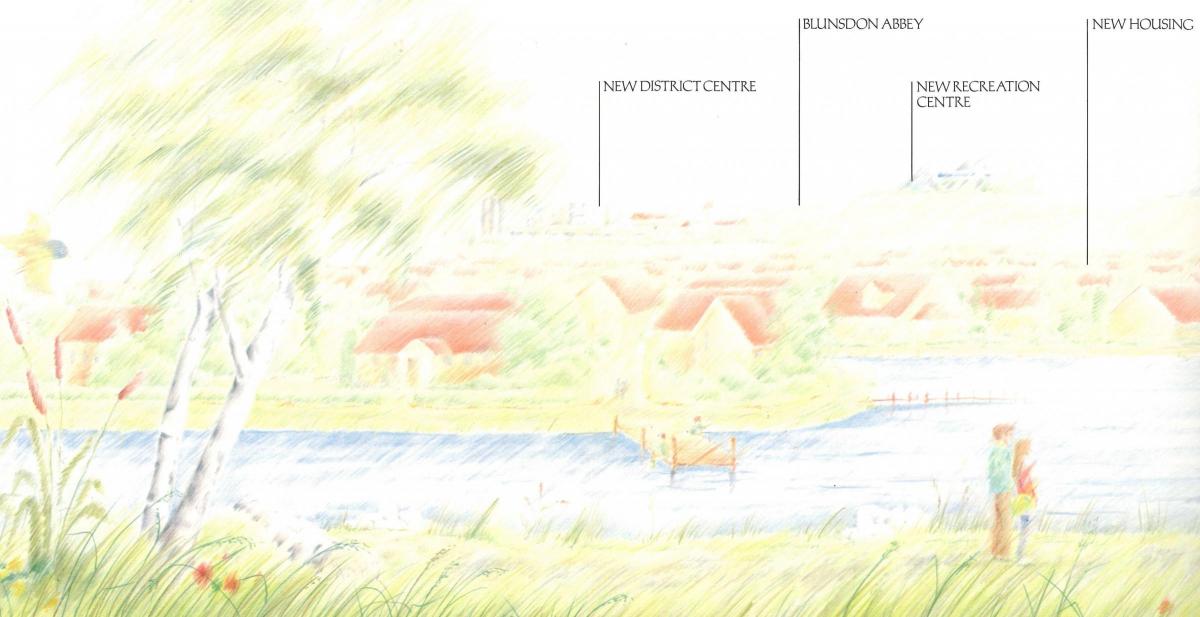

Called Building for the Community, it was filled with brightly-coloured pencil drawings of the future the companies envisaged.

Two examples are reproduced here. The larger one is part of a large fold-out panorama showing the view across a stream toward housing, a district centre, a recreation centre and, in the distance, Blunsdon.

The smaller shows a family enjoying a picnic, undeterred by the fact that they are sitting next to a road.

The introduction to the brochure notes: “The proposals continue, and consolidate, Swindon’s role as an expanding town.

“They a venture for jobs, better social and community facilities and continued economic activity, which is necessary at the present time.”

The authors strike a balance between enticing readers with happy visions of what will happen should the development go ahead and bleak ones of what might happen should the area remain untouched:

“Many parts of the country desperately need such schemes for their communities, while in others their natural economic advantages continue to create opportunities.

“Competition from other areas is fierce and, while relatively prosperous, Swindon needs to ensure that its future is secured.

“If it does not other areas will attract the commerce and industry that Swindon continues to need.”

Driving home the point rather ruthlessly, the introduction concludes: “The town’s expansion objectives were embarked upon in the early 1950s to avoid reliance on the railway works as the sole major employer.

“In March 1986, 2,300 jobs were lost when the works closed. Swindon must not be complacent.”

The rest of the brochure is divided into sections explaining the timescale of development, promising to provide excellent community facilities and detailing the size of the planned new community.

The initial planning application was for up to 9,000 new homes across 1,500 acres.

The architectural theme is described as based around the urban village concept, with houses, shops and public spaces designed to give people a sense of being in a place with its own distinct identity.

“This,” the authors rather opaquely proclaim, “means the creation of physical focal points that are also social entities.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here