THE era of big hair and Care Bears was still part of the unknown and exciting future this week in 1980.

Into the 80’s - complete with errant apostrophe - was the name of a 16-page Adver supplement devoted to likely trends in everything from fashion to technology in the years to come.

The latter was covered in an article by Tomorrow’s World presenter Judith Hann, whose suggested, among other things, that houses would become more energy-efficient as fuel prices increased.

“At one extreme,” she said, “there are a group who call themselves the Gentle Architects, who want to make tomorrow’s homes much kinder to the natural world.

“Instead of concrete blocks and acres of glass, they want homes built so that the land still looks green - which demands a new kind of camouflage.

“This means houses built underground and into the sides of hills. Or when vast housing areas are finished, soil and plants are put on top of them to make man-made hills.”

Solar and wind-power were also mentioned in the article, although the author was careful to point out that solar panel technology was still fairly primitive.

So were robots, which meant people hoping to have electronic domestic servants were likely to be disappointed.

Lovers of television were assured that within a couple of years there would be a new terrestrial TV channel in Britain, bringing the total to a breathtaking four.

The new channel - it would eventually be called Channel 4 - was described as likely to be a sort of BBC2 with adverts. It would eventually launch in November of 1982 with the first edition of Countdown.

For a Swindon man called Paul Lavelle, the decade would conclude with his claiming a place in history as the first human to take off from the North Pole in a hot air balloon.

The remarkable feat, which included enduring temperatures of 40 degrees below freezing, was one of the earliest high-profile attempts to highlight climate change.

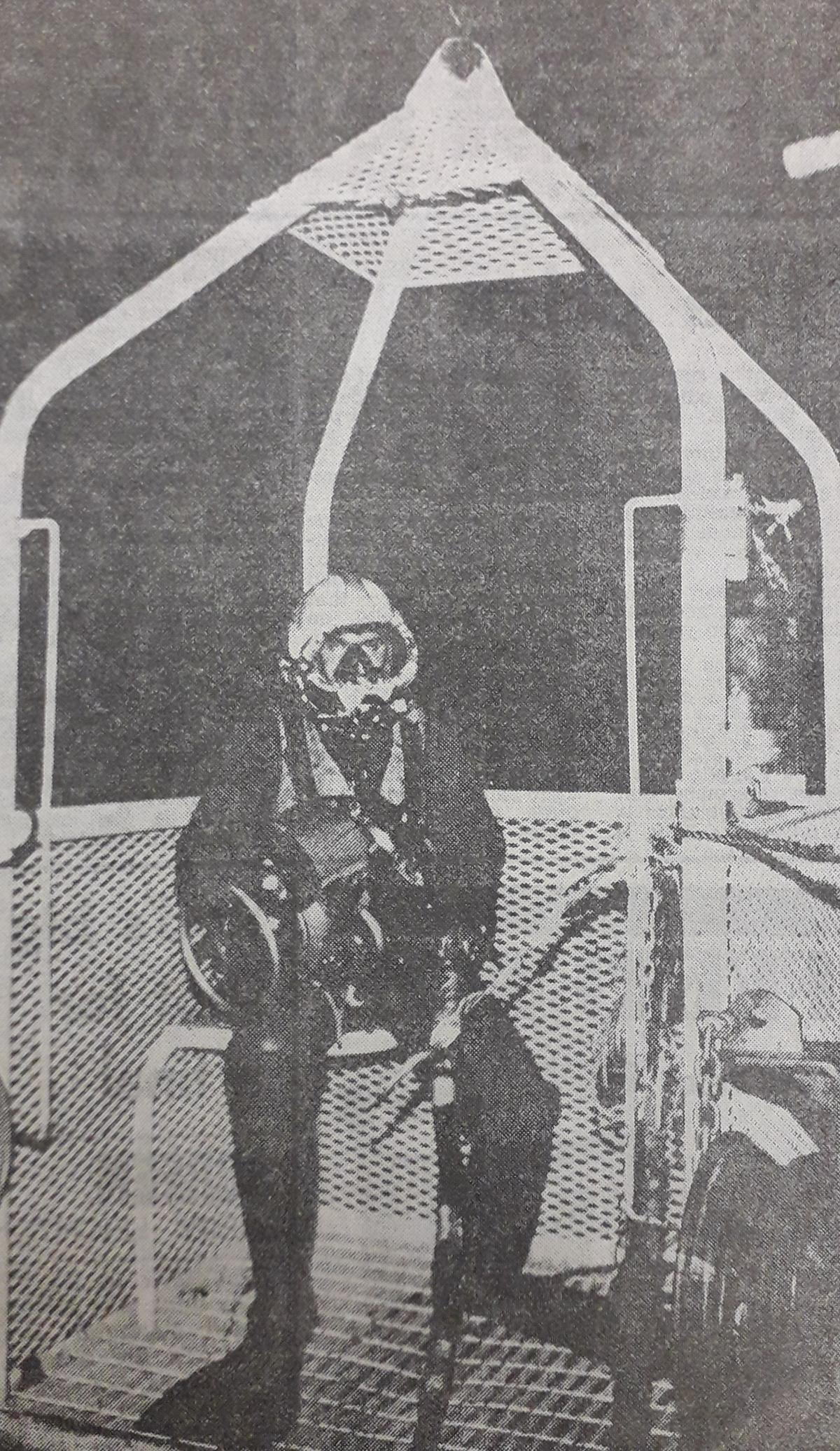

When we spoke to him in early 1980, he spent much of his life exploring in the opposite direction.

Already the veteran of a Swindon expedition to search for the wreck of a warship lost off the Channel Islands in 1744, the 23-year-old was an oil rig diver - a member of one of the world’s most dangerous professions.

He compared the working and living environment to being in prison: “You sleep two to a room and all the rooms are identical with no windows. There’s no real radio or television and you only get out-of-date newspapers.

“We work at night because there is less danger of anybody dropping something heavy on top of us. It’s always dark in the water and this makes the work more difficult.”

There was the odd amusing moment - assuming one found enormous undersea beasts with razor-sharp teeth amusing.

“The divers,” we said, “had quite a laugh about a character they nicknamed Colin the conger.

“They were inspecting a mooring point when they found a large conger eel that had been trapped there during construction - and it grew too big to get out.

“Although it was pitch dark the divers were aware that there was something in there with them.”

Colin said: “It was a bit of a joke but none of us was very keen to go down there. The conger once ate a light we lowered down - when it was pulled back up there was only a frayed cable.”

Colin’s more recent projects include founding an e-bike firm.

Rather less alarming creatures were encountered by a 39-year-old Chiseldon mum-of-four called Wendy Standfast.

In 1980 many more professions were associated with one gender or the other than happens today, so a woman becoming a shepherd was unusual enough to merit a front page picture story.

Wendy worked for local farmer Max Hughes, who rated her highly.

Pausing during preparations for a busy lambing season, Wendy told us: “I love children and when it comes to mothering ability I think it is the same whether you are nursing lambs or babies - the love and attention have to be there.”

Swindon was touched by a phenomenon which arguably had its roots in the recent invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union, which ramped up the Cold War and diminished faith in currency markets.

Investors turned to gold, just as they would during subsequent crises including the crash of 2008, and prices promptly went through the roof.

Jewellers’ shops including a Bridge Street business called Goldfinger were swamped by people hoping to cash in.

We said: “Glittering prices have tempted hundreds of people to sell their precious metal pieces.

“People are selling everything from broken chains to wedding rings and family heirlooms.

“Housewives clutching their gold trinkets crowded the counters to get the best prices for them.”

Gold had reached a value of about £280 an ounce by that time, which was more than its value 25 years later.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here