AS campaigns go, it certainly had legs – if not quite winning ones – lasting the best part of a decade and incorporating the likes of Queen Victoria, Elizabeths I & II, Charles I and royalty of a more localised variety – Diana Dors, Billie Piper, Melinda Messenger….

Naturally, there was the controversy. There usually is. “It stinks of a stitch-up,” our council leader snapped while “snide, ignorant and ill-informed,” was the irate response of one of our MPs.

Tempers flared and the corridors of the Home Office echoed with complaints from indignant Swindonians.

Oh yes, let’s not forget a perceived competition with our “rivals” along the M4 corridor, Reading. As it happened, we both lost out, but neither went down without a fight.

At the start of this month Swindon Borough Council unveiled at new ‘vision for the future,’ stating that “by 2030 Swindon, while not formerly becoming one, will have the feel of a city.”

The statement reminded me of our admirably ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful bid, which ran from 1993 to 2002, for our town cum borough to be reborn as The City of Swindon.

In the early Nineties, as the Millennium approached, all sorts of feverish schemes to mark the arrival of a New Era were in the air – from creating something called The Eden Project and a National Space Centre to a bridge, a dome and, in Wales, a sports stadium. And also – it was revealed to much excitement – a batch of new cities. It doesn’t happen that often. Towns are towns and rarely get the chance to climb into the premier league of British conurbations.

Sunderland was the most recent recipient of city status, having been elevated in 1992 to mark the 40th anniversary of the Queen’s ascension. Aspiring civic leaders across the nation, in towns which had come on a bit in recent decades, were mad for it – including Swindon.

Hold on, some of us thought, we haven’t got a cathedral, a traditional prerequisite for city status. But no, that wasn’t a mandatory requirement anymore.

Swindon threw itself into the fray and even sought the seal of approval from the populace by way of a circular despatched to all of its 73,000 homes.

Of the 7,500 who bothered responding, 65 per cent were in favour of Swindon running for city status, 25 per cent said “don’t be daft” while the obligatory ten per cent wanted more information.

It was good enough for the council and in a rare show of unity all four parties staunchly supported the city slicker crusade. (Saying ‘no, we don’t deserve to be a city,’ on the other hand, would have been political suicide.) Enthusiastically backed by the business community, a bid was meticulously put together and the phrase “Swindon – City for the 21st Century” was cheerfully banded about, provoking many a heated pub debate, often polarising beery opinion.

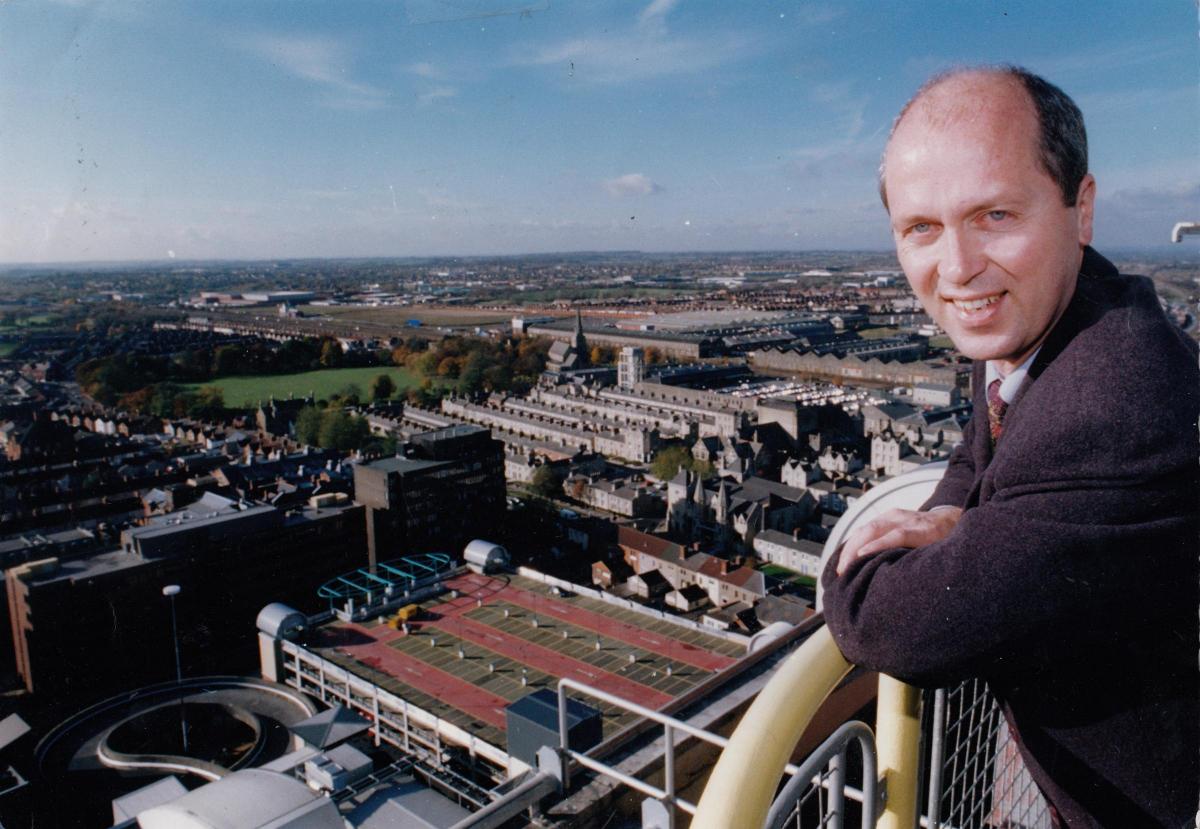

According to council leader Tony Mayer, city status would recognise Swindon’s remarkable transition from dying railway town to fast growing, economically booming metropolis.

The arrival of 2000 would also crown an important local milestone – 100 years since Queen Victoria rubberstamped the founding of a new Swindon council, joining Old Town on top of the hill with New Town at the bottom.

OK, so we haven’t got a cathedral, we haven’t got a university and no concert hall to speak of, either. Even our central library, back then, was a laughing stock collection of huts.

So what does Swindon – from a mid-Nineties standpoint – have to offer to be reconstituted a city?

A lot of worthy but somewhat unsexy stuff about a thriving economy with top firms like Honda, Nationwide, Motorola, Allied Dunbar (now Zurich) and Burmah calling Swindon home.

The ongoing regeneration of the railway works, some royal connections (see panel), an outstanding collection of modern British art, and bits and bobs more. Oh yes, we’ve got an Anglican Bishop now, too.

A reasonable bid, if a little unspectacular. Such was Swindon’s zeal to become a city that it was the first of the 39 claimants to submit its application. And then the bombshell…. As the Millennium approached, and the pros and cons of contenders were weighed up, a leaked report penned by some anonymous bureaucrat laid into our ambitions with a vengeance.

He (or perhaps she) dismissed Swindon as having “very little history” until the 19th Century, and reckoned our application gave the impression of a “materialistic town rather than a rounded community.”

We were also accused of being embroiled in a “well documented rivalry” with Reading for the title of city – pretty much kicking both bids into touch.

Cue the outrage. “I think this document is appalling. The whole thing stinks of a stitch-up,” fumed council leader Sue Bates.

Our two MPs Michael Wills and Julia Drown were positively bristling and speedily fired off angry missives to the Home Office.

Michael Wills (Swindon North) personally confronted Home Secretary Jack Straw while striding the corridors of power, having been “surprised and extraordinarily disappointed at how ignorant and ill-informed the anonymous author of this report has been.”

Swindon made the shortlist but it was party town Brighton, Wolverhampton – home to the UK’s first set of traffic lights – and Inverness, which is somewhere in Iceland, that the Queen named as Cities for the New Millennium.

All was not lost, however. Four more cities – one from each of the home nations – would be created in 2002 as part of the Queen’s Golden Jubilee celebrations. Bruised but unbowed, Swindon’s bid would be bigger, better and, as it happened, sexier.

Chief executive Paul Doherty announced: “Swindon is positively moving forward in its bid for city status” and revealed that a task group had “put their heads together to meet the Lord Chancellor’s criteria.”

Our Three Fab Blondes – Dors, Messenger and Piper – were named in Swindon’s dossier, highlighting our local lasses made good. Diana, in particular, had been the nation’s very own sweetheart – a bodacious blonde bomber who brighten the dour post war era.

Swindon’s Royal Heritage in the criteria’s Section B was keenly researched and even mentioned our avuncular Golden Lion, erected in the town centre for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977.

As it happened Preston came up trumps, prompting a headlines such as: “Fury of a town spurned….again.”

Julia Drown insisted: “We are a city in all but name” before adding: “One day I feel sure that here in Swindon we will be celebrating city status.”

Either in a fit of pique or as an “up yours” to the decision-makers, those cheeky chaps in Reading inserted the words “city centre” on their buses and car park signs. So there.

Personally, I can’t imagine ever hollering “Come on you City” from my berth in the Don Rogers Stand.

<li>CITY status in the UK is granted by the monarch. Britain currently has 69 cities – 51 in England, six in Wales, seven in Scotland and five in Ireland.

City status gives no special rights other than the prestige of calling itself a “city.” The last towns to become cities were Chelmsford and St Asaph in Wales in 2010 to mark the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee.

With a population of 3,355 St Asaph is Britain’s second smallest city (St David’s Peninsula is the smallest) – so size doesn’t matter after all.

In 2010 Swindon’s then council leader Rod Bluh poo-pooed the idea of mustering the troops for another city status campaign if the opportunity arose.

“I’m more interested in tackling the real issues facing Swindon, rather than chase titles such as this,” he declared.

<li> HERE are some royal connections the Swindon task group included in its 2002 city status bid:

l Elizabeth I visited Lydiard House with her privy council in 1592

l Charles I granted a charter to Thomas Goddard to hold a market and fair in Swindon in 1627

l John St John of Lydiard House was a staunch Royalist who lost three sons in the Civil War.

l Queen Victoria signed the charter that amalgamated Old Swindon with New Swindon in 1900.

l Prince Charles was taught steeple chasing at Wroughton Stables and also opened the STEAM Museum.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel