IT is easy to imagine Horace Thompson breaking into a smile as he recalled nearly 70 years later that rare, wonderful moment of comfort and joy which magically materialised amidst the carnage and suffering on that most infamous of thoroughfares

Lined with skeletal trees and located amidst a sea of mud, dead horses and shattered vehicles just outside of Ypres, the Menin Road could easily have been described as the highway to hell, even by the horrific standards of the trench-laden Western Front.

“It was awful,” remembered Horace, then in his late 80s. “Shells were bursting all over the place.” The worst section was nicknamed Hell Fire Corner, a crucial junction that British and Commonwealth troops had to negotiate before reaching the battle zone.

The spot was covered by heavily armed German positions which showered deadly shells and unremitting machinegun fire upon our boys. “The Germans had their guns trained on it. You had to run for your life as you passed.”

Marching to battle along the Menin Road one day - and this really clung to the memory - the British battalions were in for a pleasant surprise. “Who should be there but the Salvation Army giving every soldier a cup of cocoa before we went off to the battle line.”

Horace paused for a second before adding “how glorious,” as if still savouring that steaming, welcoming mug.

There is a certainly poignancy here – how a simple cup of cocoa should stick so vividly in the mind of Swindon pensioner Horace so many decades later.

Horace endured four years of warfare on the Front having watched many of his pals perish. He fought in some of the greatest/worst encounters of the 20th Century – Ypres, Passchendaele, the Somme….the latter of which was raging exactly a century ago.

By sheer luck he escaped death on several occasions. A lifetime later, Horace did something remarkable. Urged on by daughter Sheila Marcer of Swindon he recorded his memories of The War To End All Wars.

Over two or three taping sessions during the mid-1980s, retired male nurse Horace, who died at 95 in 1991, provided in an undramatic, matter-of-fact sort of way a fascinating, evocative account of one private’s war.

Horace, a Sheffield lad whose grandson is Swindon publican Andy Marcer of The Beehive in Prospect Hill, was 18 when he volunteered for the 4th York and Lancs in September 1915 – largely to escape the hardship of long hours and low wages.

After six months training “we were packed off to France to fight The Bosh” - and was almost blown-up within weeks. Carrying a wounded soldier he recalled: “We were going along a trench when a shell burst between us.” But “it was a dud, so we escaped being killed.”

Deployed at various strategic locations along the Front in Belgium and France, Horace’s battalion was under constant rifle fire with “shells dropping all the time.”

On one occasion “it was very, very hot. We had no water. There was a river at the bottom of a ridge that we were firing from. But we couldn’t get any because every time we sent someone down to get water they’d get killed.

“We put our ground sheets out to catch water but there was no rain at all. We were absolutely going mad with thirst.”

They eventually retrieved some liquid relief although many of the poor mules that carried the precious supplies were “blown into the trees” by enemy shells.

The utter futility of this particular episode, setting a familiar pattern, was not lost on Private Thompson. “We were relieved after a month having done nothing at all…..we captured nothing.”

Men, meanwhile, were constantly dying around him including his officer who he had been at school with a few years earlier.

Night patrols were a regular duty, sneaking towards the enemy either to check out their positions or fire on them, occasionally from behind German lines.

Before one such nocturnal escapade Horace remembered: “One of my pals asked not to go on this raid because he was going on leave the next day to get married.

“Low and behold, the poor devil got killed. That upset us all. We couldn’t do anything about it…an order’s an order and you have to do it.”

Daylight raids to destroy machine gun posts were another regular occurrence. One time “we killed all the Germans and dismantled their machine gun.”

They captured around 75 prisoners and Horace was recommended for a bravery medal, having led a bayonet charge down the street, prompting The Bosh to come out waving white flags.

“I never got it. The officer that recommended me got killed. But that (the medal) didn’t matter,” he shrugged.

Years later his local postman told him he got his arm blown off during the same encounter.

In the trenches of the Somme “the Germans were only about 50 yards away from us. We used to throw bombs at one another.”

Potato mashers, they called the German grenades. ”They looked like potato mashers with strings attached. You pulled this string and threw it and it blew up. But many a time they threw it and it didn’t go off, and we threw ‘em back…”

“Our grenades – shaped like eggs – were marvellous,” he enthused.

You had to keep your head down in the trenches, said Horace, who witnessed many-a-casualty from enemy snipers. “A friend of mine put his head above the trench and got picked off.”

A particularly horrific image continued to haunt Horace for the rest of his days - “legs and arms sticking out of the trenches” at the Somme.

Before one British attack, the lads were ordered to ignore any of their pals who were hit and to carry on regardless - “which I thought was awful,” he said.

“I had a friend and I said ‘if you hit I’ll stop with you’ and he said he’d stop if I got hit, too. Luckily, neither of us got it.

A mate, however, died when a piece of shrapnel pierced his helmet. “It was no more than needle and it killed him.”

Outrageous fortune struck when Horace briefly left his post only for a German shell fall on the exact spot where he was standing minutes earlier. “I was really fortunate,” he remembered with some understatement.

Another encounter in the woods saw many of his colleagues fall. “I escaped, as luck would have it….”

At Arras they went over-the-top with fixed bayonets in broad daylight. Once more Lady Luck smiled upon Private Thompson.

A German bullet smashed into his upper leg. But instead of leaving Horace lying in the mud bleeding to death, it struck his cap badge and knife that he kept in his pocket. “It saved my life,” he said (see panel.)

Another time one of the officers threatened Horace’s battalion: “If anyone leaves the trench I’ll shoot him.”

Experienced, war-hardened Horace bellowed back: “If you shoot anyone here I’ll shoot you.”

Later they were in a captured German dug-out when a shell exploded. Burned on the face and hands “my clothing was on fire, it was put out by pals…”

That was it for Horace. Shipped back to Blighty he was recovering in hospital when the news came through…..the war was finally over.

- WHEN all leave was cancelled during early summer of 1917 Horace and comrades knew “something big was up.”

The “big do” was Passchendaele – a murderous and lengthy slog later lambasted by Lloyd George as “one of the greatest disasters of the war...no soldier of any intelligence now defends this senseless campaign.”

This is how Horace remembered it: “Awful, terrible….

“I was a Lewis Gunner, number one on the gun – they fired 500 rounds a minute. Number one fires it. Number two puts the bullets in.

“We went in 800 strong and came out with 80 odd. I was one of the lucky ones…. again.”

Horace continued: “Six months at Passchendaele. There were hundreds of soldiers wounded but nothing could be done about them because they couldn’t get them away. They hadn’t enough Red Cross men or stretcher bearers.

“Moaning and groaning, a terrible state they were in.

“Passchendaele was mud and still more mud,” added Horace who remembered being “up to the waste in water, firing my gun…”

- “IF it wasn’t for that I wouldn’t be here.” Pub landlord Andy Marcer is examining some scraps of steel that a century ago belonged to his grandfather.

They were once Horace Thompson’s army knife-and-fork combo that was shattered when it was struck by a German bullet.

Horace kept it in his trouser pocket and it saved his life. “It’s a remarkable story,” said Andy, 57, of The Beehive in Prospect Hill, referring to Horace’s recordings of his World War One exploits.

His grandfather occasionally recalled the war but only when prompted, said Andy. “It wasn’t that he didn’t want to talk about it, he just didn’t think anyone was particularly interested.”

Andy was “absolutely gobsmacked” when he heard the recordings. “I saw him in a different light.”

During the 1920s Horace married Andy’s grandmother Edith and spent his working life as a male nurse and strong union man in Yorkshire before later joining his family in Swindon.

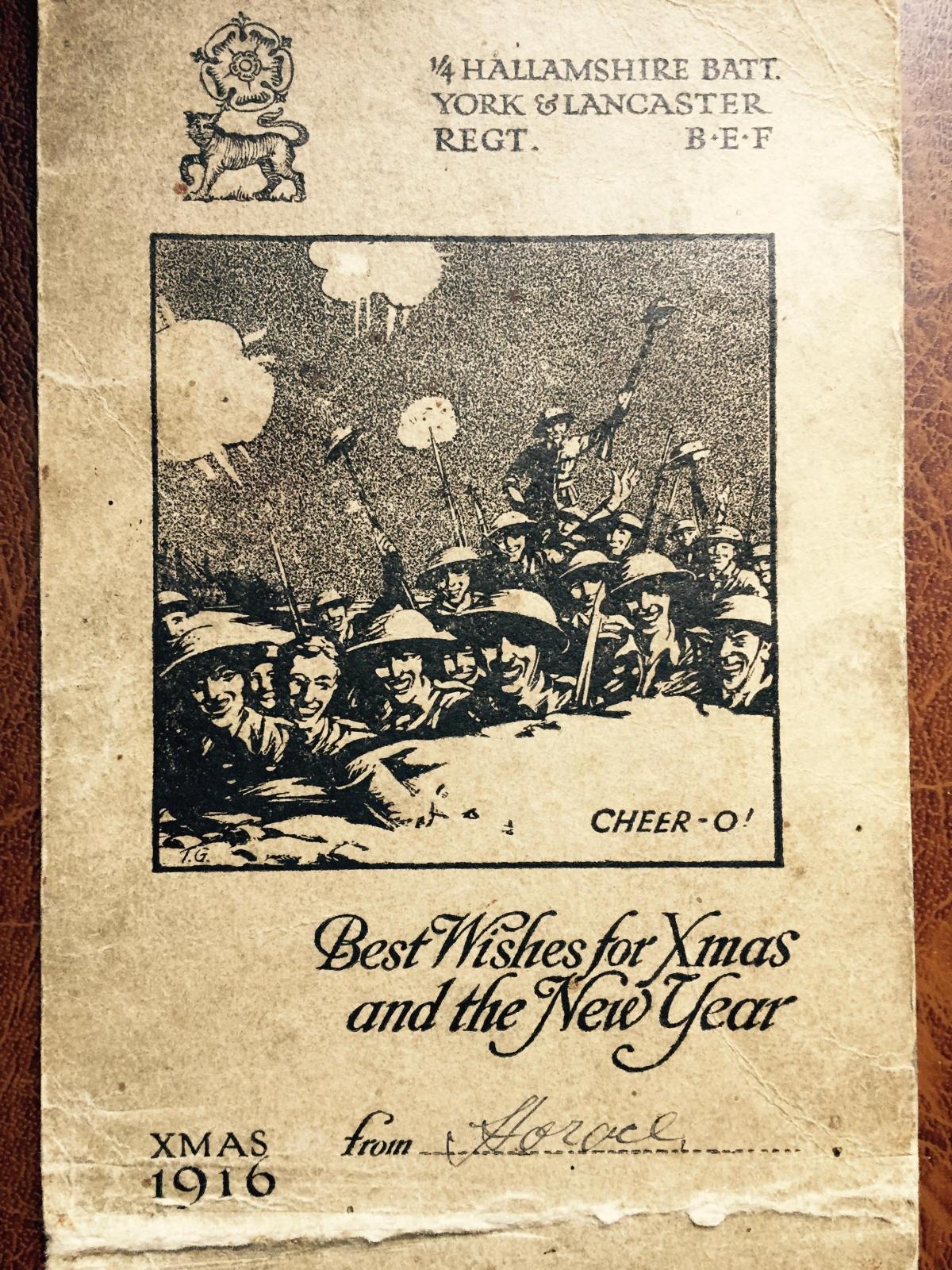

Horace left a number of Great War ‘souvenirs’ when he died – including his service medals and a 1916 Christmas card mailed from the trenches.

“I’m so glad mum taped his war-time memories. It’s a wonderful family heirloom.”

- WHEN Horace was demobbed on March 26, 1919 he was given a war gratuity of 20 pounds and ten shillings – equivalent to around £1,300 today.

They also issued him with “a ready-made suit which was rubbish.”

When he began looking for work he applied to become a tram conductor but was turned down because he wore glasses.

That’s right, he fought for four years in one of the worst wars in history but wasn’t deemed fit enough to issue trams tickets.

Bet the little squirt who rejected him saw out the war from safety of his tramways office!

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here