WHEN Isaac Fowler’s heart gave out without warning five years ago, his family were left grappling with the unbearable reality of a life without him.

Little did they suspect that his death would be the key to uncover a genetic disorder passed down through generations and save not only his mother but spare four of his relatives.

"We were completely lost without him,” says his mother Helen. “What happened was horrible. But if he hadn't died no-one in the family would have known, unless somebody else had died of it. What happened to Isaac could have happened to any of us. It's meant that thanks to him we've been able to protect other members of the family. That's the positive in this sense."

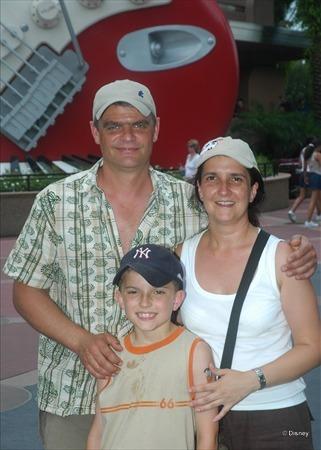

Isaac was 14 years old when he collapsed in his room one Saturday night in June 2011.

"He was upstairs in his bedroom getting ready to go in the shower," recalls the 48-year-old from Haydon Wick. "He was meant to do be doing some revision because he was doing some GCSEs early. I shouted up to him but didn't get a response."

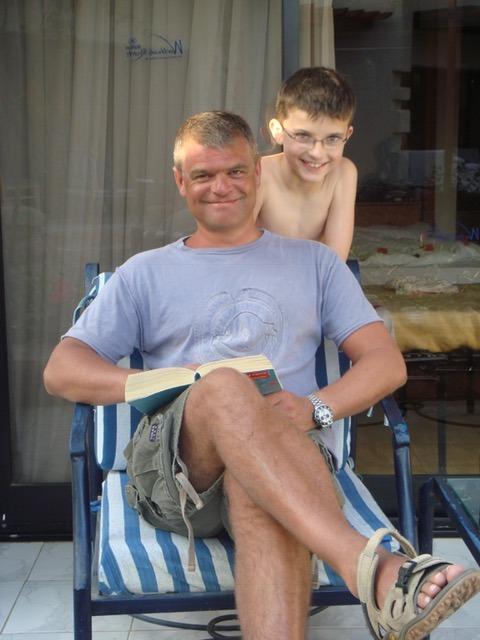

It was already too late by the time his stepfather Sean Warren hurried up the stairs to the bedroom. Isaac lay unconscious splayed on the ground. Sean performed CPR until the paramedics arrived and rushed their son to the Great Western Hospital. The memory of breathing air into the inert teenager's lungs, pressing down on his chest to jolt his heart back to life still haunts him today.

"Helen went upstairs and there was just a big scream," says the 52-year-old owner director of an engineering firm. "She called me up and I could see him from the landing. It was just as if his body, his heart just turned off.

"I started to do resuscitation. When this happens your lungs can fill up with blood and when you do mouth to mouth some of it can come out. I still get that metallic taste in my mouth sometimes, on anniversaries, birthdays, anything that triggers the memory. All I kept thinking was, ‘It’s too late, it’s too late’."

And yet, by their own admission, at no point did either of them, nor Isaac's father Paul Fowler, who joined them soon afterwards at the hospital, ever abandoned hope their son would come round. The paramedics were still "working on him" and showing no signs of giving up on their boy. But to their dismay, 65 minutes after they discovered Isaac's listless body on his bedroom floor, the 14-year-old was pronounced dead.

"They never got his heart going again," says Helen, her voice trailing off. "Until then I don't think I could have thought that he might die," adds certifications and compliance manager. "He was rarely ill. He was just 14."

"Isaac was in the room next to us," continues Sean, still disbelieving. "We were all sat around in silence but it's as if the biggest conversation was going on."

Beside themselves with grief, they were immediately subjected to police questioning - a formality to ensure nothing sinister was at play. They were held in hospital until their home was thoroughly searched by investigators.

"I just wanted to get out of there," confides Helen. "We were just numb sitting there, not believing it. And I was just shocked when the medical staff said that police would have to come and interview us because, why would they? But they had to do their job."

Distraught and dazed, they were unable to mourn their son or begin the agonising process of picking up the pieces of their shattered life until the post mortem results finally lifted the uncertainty shrouding the cause of his death.

"We needed to be able to draw a line and be satisfied with the explanation," adds Sean.

But far from the step to closure they were yearning for, the report's findings left them dumbfounded and desperate for answers. It suggested Isaac had succumbed to a severe asthma attack. But the teenager, his parents insist, had not suffered from the condition since childhood. The facts simply did not add up.

"The three of us thought, 'This is absolutely not what he died of.' We were aghast that they had put asthma down. He had been running around the afternoon before he died and he was a little puffed out. But we found him on the floor, there was no sign of struggle. There would have been a struggle with an asthma attack. At that point, the focus shifted on finding out why he died."

Another possible hypothesis according to the post mortem was arrhythmia - or abnormal heart rhythm. Helen, Sean and Isaac’s father reached out to the British Heart Foundation, which arranged for genetic testing to be performed at the Oxford Medical Genetics Laboratory and shed light on their son’s unexplained collapse.

He was found to be carrying the Long QT gene, which increases the chance of a dangerous heartbeat rhythm and affects around one in every 2,000 people.

"The more we found out about it, the more it made sense," says Sean. "We felt we could move on once we'd found out why."

But it was not quite as simple for Helen. As Long QT is passed down by parents and runs through families, she was riddled with guilt at the prospect of having transmitted the gene which eventually claimed her son's life, she admits.

One by one, the family underwent genetic testing. She was found to carry the gene along with four of he relatives, including her father and uncle. Thankfully the condition was easily treatable with beta blockers.

“We were worried after we lost Isaac that it might happen to someone else in my family; we didn’t want anyone else to go through that pain,” she says fixing her gaze on Sean. “My brother had just had another baby. In my head all I kept thinking was, ‘If I have it, my brother could have it and then one of his children could die.

"It’s horrible knowing that I passed it on to him. It was a mixture of emotions because it was because of me that Isaac had this condition. But there was no way of knowing whether I had it or he had it. And I was relieved to know that my family and I could be treated.”

Throughout, meeting their son's schoolmates and teachers at Nova Hreod, and glimpsing a side of him they never would have been privy to otherwise, was a huge comfort, Sean explains.

"I was very proud of Isaac because we ended up learning the secret life of a teenager, and how extremely popular he was. I was blown away by that."

Helen smiles thoughtfully. "He was very laidback. He didn't bother with all the cliquy-ness at school. He didn't have friends in one group. Although yes he was a teenager and we had seen the occasional moodiness, we didn't get stropping and door slamming. He loved watching sports. He toyed with the idea of being a sports journalist for a while. In the end he decided to be a primary school teacher. He had arranged to do some work experience at Haydon Wick Primary School but he never got to, unfortunately."

After receiving counselling and facing head on the loss of their son, Sean and Helen made the decision to adopt two vulnerable children. They felt, they admit, an unfulfilled longing to parent again. Ensuring they were taking them in for the right reasons, not as substitutes for Isaac, was essential.

"It would have been so easy but so wrong to try to replace Isaac," says Sean firmly. "So we waited awhile. We made sure we went through the grieving process - and we still are. But they've given us a life. They’re not Isaac, they have their own personalities. With Isaac we had a path and suddenly that path was no longer there. We still had some parenting left in us. Such a huge part of your life is suddenly not there anymore. Your children are your biggest reason to get up in the morning."

Isaac's memory endures and pervades their lives each day. Songs playing on the radio, even flipping pancakes on Shrove Tuesday - "he loved pancakes," Helen chimes in fondly - are bittersweet reminders of the boy that was snatched away from them. Sirens still fill Sean with dread.

"It puts shivers through me," he says, his whole body tensing up. “When I hear the song we played at his funeral, I have to pull over when I'm driving. It's Christmas, birthdays, Father's Day."

"They say that time heals, well it doesn't," sighs Helen. "You learn to live around it. You still have a hole and you grow your life around it but it will never go. But something like this makes you appreciate life more. You wake up in the morning and you think, 'I'm alive' and that's a good start to the day."

Sean and Helen are urging people in Swindon to support the British Heart Foundation’s Miles Frost Fund, which aims to raise £1.5 million to help make genetic testing available to all families affected by the deadly heart condition hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. To find out more go to www.bhf.org.uk.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here