The Great Western Railway mounted a very successful campaign to sell itself to the public by creating a demand for its seats and excursions.

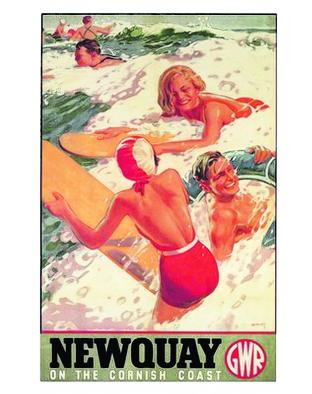

So much so that it created a vision of an idyllic countryside communicated through eye-catching, gaily-illustrated posters.

They were all aimed at tempting people away from their humdrum lives and the daily grind of factory and office work to such wonderful places as Torquay.

It worked well and a whole industry of artists, publishers and printers grew up to feed the railway’s insatiable demand to sell its tickets to “Speed To The west.”

Using terms like the Cornish Rivera express or Shakespeare country gave the people of the British Isles a tempting view of far away places and beauty spots.

Bob Pixton, from Swindon, in his latest book entitled Great Western In Shakespeare Country, writes of the marketing that the GWR carried out in America in the 1920s and 30s on the radio and in publications to sell to the professional class.

It created a branded GWR mirage of rural England by using catchy phrases such as The National Holiday Line or The Line Of The American Pilgrim. It worked and Americans flocked to the area, bringing in a much-needed boost to tourism.

What is interesting is that the posters are now much sought after railwayana and originals change hands at auction for large sums of cash.

The artists have become famous and the style has endured, though today no one in the New Railway World bothers with such unique marketing ploys.

Railway painters produced posters well into the latter days of British Rail, before being stamped upon by package holidays, and the British penchant for Dr Scholl sandals, Watney’s Red Barrel and fish and chips in Torremelinos, so typified in a Monty Python sketch from about 1970.

Package holidays abroad replaced cockles, candyfloss, kiss-me-quick hats and saucy postcards with indecent haste.

Indeed, the change was so fast that it left the seaside resorts of this country well and truly beached.

They were quickly viewed as some sort of embarrassing Victorian curiosity.

Why had so many people deserted Torquay for Torremelinos? It can’t all have been sun, sea and sangria.

The reason was that it, like many other resorts and the railways, had had its day.

A new generation of people could fly cheaper than they could travel by overcrowded, tired railway rolling stock.

Under-investment in railways helped to strangle our thriving resorts and holiday destinations.

But one thing that remains as an iconic image of lost summer holidays is the 900-yard Barmouth Wooden Viaduct which still meanders along the Cambrian Coastline. You can actually pay a toll to walk cross this bridge – well you could last time I went.

If you want to read more from the Bob Pixton book mentioned, it costs £15.95 from Kestrel Railway Books.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here