IT was, as Roger Gale, eminent member of the Society of Antiquaries of London so eloquently and tantalisingly put it in 1728 “the finest pavement that the sun ever shone upon in England.”

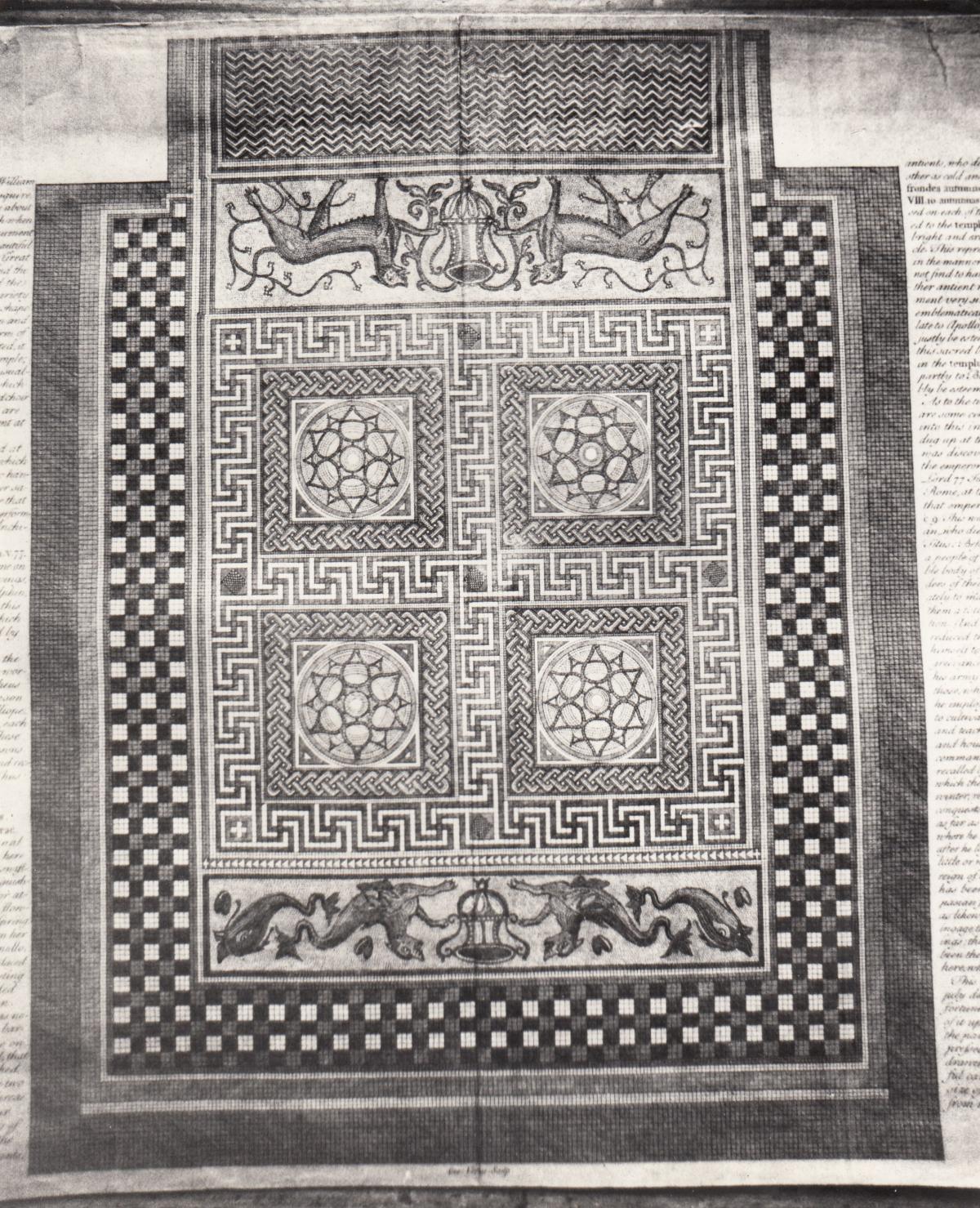

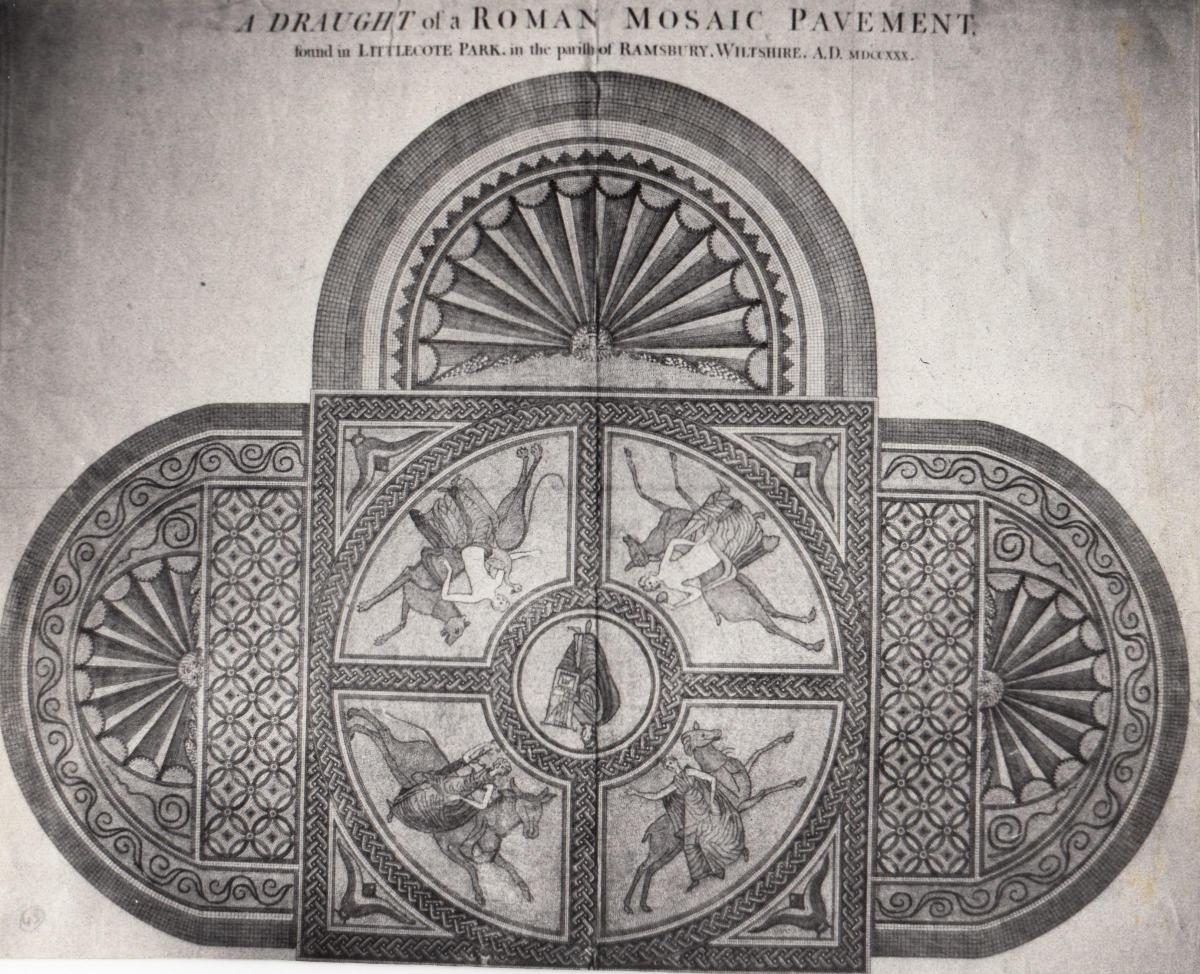

Such was its significance, so exquisite its craftsmanship, that no sooner had it been found after well over a millennium beneath the Wiltshire soil than an engraving was scrupulously made by a leading artist of the day to convey its splendour to the outside world.

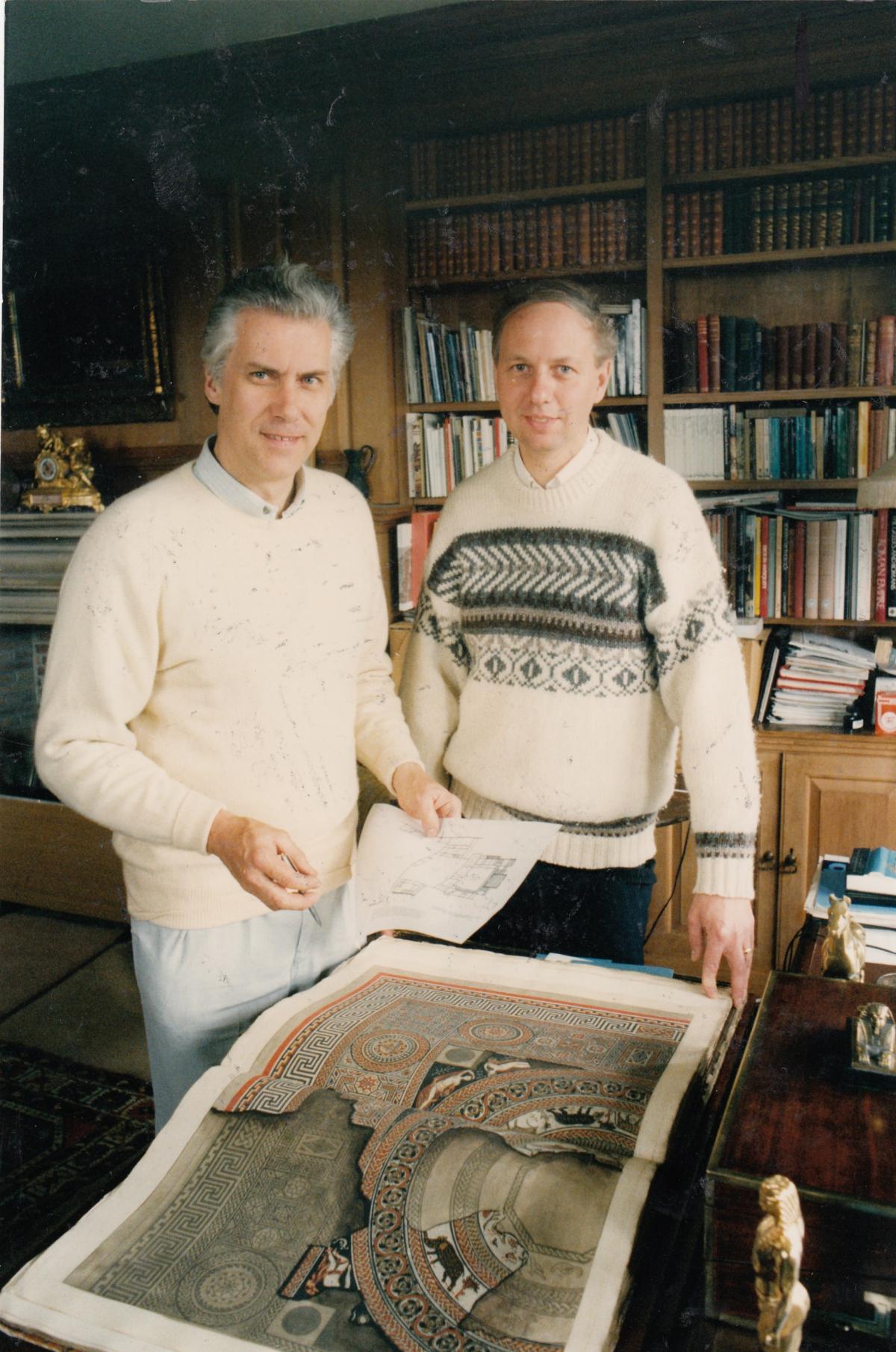

It was George Vertue’s finely detailed image, along with Gale’s mouth-watering eulogy that cast an enduring spell over Swindon archaeologists Bryn Walters and Bernard Phillips some 250 years later.

Surely the magnificent Orpheus Mosaic that was again lost to the world during the 18th Century so soon after its rediscovery, could once more be located, they hoped.

Its whereabouts – if it hadn’t been destroyed, as some feared – were roughly known... in the rolling parklands of Littlecote House near Hungerford.

But no-one knew the precise spot. No-one had a map marked “x.”

Bryn, who is now director of the Swindon-based Association for Roman Archaeology, recalls: “I knew about the mosaic from my later childhood when I used to read about archaeological sites in Britain.

“In my youth when passing through Chilton Foliat on buses, I used to look across the valley towards Littlecote House and its park, thinking to myself that one day I’ll go and find it – hardly believing that one day I actually would.”

Bernard remembers: “Bryn and I had been aware of the mosaic’s existence for many years, having seen George Vertue’s illustration in Sir Richard Colt Hoare’s ‘The Ancient History of Wiltshire Vol. II.’

“This describes it as having been found ‘in a low piece of ground near a river in the park of the Popham family at Littlecote.’

“He also states that ‘This curious piece of antiquity is now unhappily destroyed.’”

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the discovery – or rediscovery, if you like – of a Roman complex containing one of the Jewels of Romano Britain... thanks to the perseverance of Bryn and Bernard, with a little help from some rabbits.

Around 1,650 years old the Orpheus Mosaic was created on a site already occupied for around three centuries following the Roman Invasion of 43AD.

Housed in an exotic hall, it formed an extension to a once imposing villa complex before it was abandoned, lost and forgotten during the onset of the Dark Ages in the 5th Century.

Some 1,300 years later, in 1727, Littlecote House estate steward William George was poking around the gardens of its hunting lodge on a bend in the River Kennet when he stumbled upon something quite magnificent... the long-concealed Orpheus Mosaic.

The Society of Antiquaries of London grandly announced the astonishing find the following year – triggering excitement, the commissioning of Vertue’s intricate engraving and Gale’s awestruck comment.

And then, a few years later, history repeated itself when the mosaic once more simply vanished. Gone it may have been but forgotten it was not. Periodic searches, however, all drew a blank.

Scouring North Wiltshire for Roman sites in 1976, Bryn obtained an aerial photograph indicating archaeological remains in the suspected vicinity of “England’s finest pavement”.

Spades in hand and hearts pumping, Bryn and Bernard set off across the fields of Littlecote on a drizzly day 40 years ago with estate owner David Seton Wills towards a recently ploughed area where a site of ancient habitation had been suggested from the air.

Having kicked around there for a while without finding anything, Bernard felt they were in the wrong spot.

He remembers: “Leaving Seton and Bryn digging a hole, I wandered down towards the river. Here it was immediately evident, in a grassed paddock and lying under old oak trees, that hollows and banks defined traces of former human activity.

“Walking amongst these earthworks I found, where rabbits had been digging a burrow, numerous stone tesserae – mosaic cubes – as well as pieces of pottery and tile.

“It indicated occupation over a very long period.”

He could hardly keep the grin off his face as he showed Bryn and Sir Seton what he had found.

Months later Bryn returned to make further excavations and, says Bernard, “astonishingly came down on the mosaic, revealing part of the figure of Orpheus. The lost Littlecote Mosaic had been rediscovered.”

Bryn says today: “What Bernard had previously found were tesserae from floors in the main Roman house on the slightly higher ground away from the Orpheus chamber.”

He told the Adver at the time: “The rabbits had thrown some cubes out. Our reaction was one of total amazement. People had been digging for it for 200 years.”

After positively identifying “the famous floor,” Bryn and Bernard oversaw major excavations which began in earnest in 1978 and continued unbroken for 13 years.

First they focused on the area of the mosaic, painstakingly uncovering hundreds of thousands of tiny pieces of coloured stone varying from a square inch to the size of a nail head.

Packed into boxes, they were sent to London where experts meticulously re-assembled the 1,650 year-old jigsaw in its spectacular entirety before it was returned to Wiltshire and re-laid in situ.

Many of the original tesserae had been destroyed after exposure to nature and the elements and were replaced with new ones based upon Vertue’s engraving.

Further excavations over the years revealed the remains of a once huge and luxurious villa complex that had evolved over around 350 years and that would have met the needs of a wealthy family and its servants.

At one stage it boasted at least five 40ft towers, akin to a small fortress.

Bryn said: “As each part of the site was fully excavated, we set about restoring and conserving the main Roman building before moving on to the next area – a unique operation which had never been done before.”

The fourth largest Roman mosaic found in England and Wales, it is 42ft long and 28ft across at its widest. Its original purpose, however, is not without controversy.

Orthodox opinion insists that it was added to the villa as a summer dining room. However Bryn is among those convinced that the site, with the mosaic as its centrepiece, became an “Orphic-Bacchic cult chamber,” built to honour the ancient, pagan gods in a predominantly Christian Europe.

- The mosaic’s rediscovery was the impetus for Bryn forming the Association for Roman Archaeology whose members receive three magazines a year and free entry to most UK Roman sites and collections. Further information: www.associationromanarchaeology.org.

- SOON after the 43AD Roman Invasion soldiers built a bridge over the Kennet on the future site of Littlecote Park as part of a supply route west.

- Their ramparts were later dismantled and the site passed to farmers who built huts.

These were replaced by timber buildings which later made way for flint walled structures including a two storey house with bath suite.

Over the decades the estate evolved as newer, larger buildings emerged that included sophisticated bathing systems.

Towered wings were added during the 3rd Century and further extensions, including mosaic floors, also appeared.

The Orpheus hall and mosaic was created circa 360-362, suggesting the site had become “a form of pagan monastery”.

The complex declined during the 5th Century and the site was occupied on and off for centuries before the Littlecote estate began to take shape from the 13th Century. - THERE is a simple explanation over how the Orpheus Mosaic was “lost” in the 18th Century so soon after it had been found. That’s because, in all likelihood, it wasn’t actually lost but rather hidden by self-serving Littlecote owner Sir Francis Popham. A letter exists of Popham urging William George, who initially uncovered the mosaic to cover it up again. He instructed George to bury it... “as I want the land for my sheep.” That’s right, he didn’t fancy sightseers trampling over land where his sheep grazed. Those seeking the lost mosaic were further thwarted after Ordnance Survey map makers were instructed, probably on purpose, that the site was quarter of a mile from its actual location. When Bryn Walters re-discovered the mosaic it was 15 inches under the grass and badly damaged. “Two sheep had been buried through it, two trees had roots going through it, and there was evidence of frost damage.” There was also claims of a bungled 18th Century attempt to lift the mosaic, explaining how a now restor

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here